Art, Mobility and Identity in The Western Himalayas

Notes on some rediscovered manuscripts in

Western Tibet and Nepal and their artistic context[1We thank Tsering Gyalbo, Romi Khosla, Gudrun Melzer and Kurt Tropper for their helpful suggestions in respect of this study. Thanks are also due to the Negi family in Pooh/ Kinnaur, India for the hospitality and help they extended to us, in particular Lama Sushil and Tenzin Negi. It is due to the discoveries and the initiative of Thomas Pritzker and his family - who first visited Dolpo in the 1970-ies - and Amy Heller who presented various aspects of these important finds in her 2009 book that this comparative study was possible.]

by Eva Allinger and Christiane Kalantari (with an appendix by Gudrun Melzer)[2Eva Allinger is research associate of the research project P21806-G19 (see below) at the Institute for Social Anthropology, Academy of Sciences, Vienna. Christiane Kalantari is researcher in the project 'Society, Power and Religion in Pre-Modern Western Tibet: Interaction, Conflict and Integration (P21806-G19) funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF). The projects are carried out under the direction of Christian Jahoda at the Institute for Social Anthropology, Centre for Studies in Asian Cultures and Social Anthropology, Austrian in Academy of Sciences, Vienna. Gudrun Melzer is lecturer and researcher at the University of Leipzig (Institute for Indology and Central Asian Studies).]

(click on the small image for full screen image with captions)

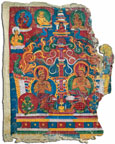

Fig. 1As far as is currently known, the earliest Tibetan manuscript illuminations dating from before the thirteenth C have only survived in the form of images on single folios. As Paul Harrison (2007: 231) has pointed out, hitherto scholarly interest has often been confined either to the illustrations in the manuscripts as isolated images or to the folios solely as bearer of texts. The finds at Dolpo and Amy Heller's documentation (Heller 2009; cf. also Pritzker 2009) of them have substantially enlarged our knowledge of early Tibetan miniature painting. Although the Dolpo region today belongs to Nepal, it had close political and cultural ties with the West Tibetan kingdoms from the seventh C onwards (Heller 2009: 17ff.)[3Dolpo is described by Wa gindra karma as part of mNga 'ris (Vitali 1996: 159); bKra shis mgon (Tashi-gön), ruler over Guge-Purang, was also sovereign over Dolpo (Heller 2009: chronology, p. 224).] (Fig. 1). On the basis of the illustrations the processes of cultural transfer will be examined and the integration of models to make a wholly new artistic entity, creating an entirely new type of manuscript in comparison to those produced in India and Nepal.[4Furthermore in recent years a huge body of manuscripts has come to light in many places, some brought from hiding places to monasteries or found in locked chambers in temples, which allow comparative research to be undertaken on manuscripts from various centres of historical Western Tibet.] The following study will focus on the relationship between text and image, transgressing as it were the 'traditional' borders between genres. The close connection between manuscripts and mural paintings will be illustrated with concrete examples. In addition, this study will examine both how architectural elements were transformed to represent a typical sacred space and the way in which the importance of donors was emphasized in a previously unknown form.

Manuscript Illuminations

It was from the Indian palm-leaf manuscripts that Tibetan books adopted the format of loose rectangular sheets inscribed horizontally and preserved between wooden covers. Wholly new potential arose not only from the fact that the sheets were made of paper rather than palm leaves, which were not available in Tibet, but that the organisation of the illuminated books developed independently of their Indian models.

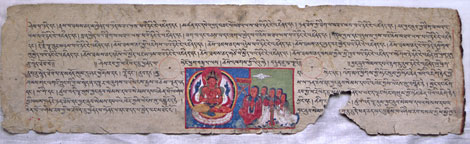

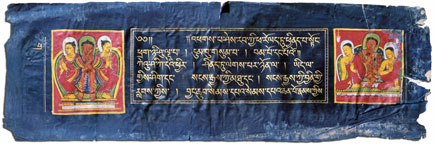

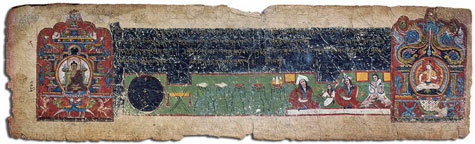

As a rule palm leaf manuscript leaves are divided up according to a strict scheme: there are three blocks of text which are separated by the sections around the string holes. If images are inserted - as a rule one or three - these are situated in the middle of the central block and additionally in the middle of the lateral blocks (Fig. 2). In Tibetan manuscripts on the other hand the images often seem to have been inserted into the text in an arbitrary fashion, a phenomenon that can be observed particularly in the case of single surviving folios[5This can be frequently observed in the case of folios found at Tabo; in the case of folios such as those acquired by Tucci in Tholing, today held in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (M.81.90.6.6-17) (Pal 1983: 123ff. and Harrison 2007), the illustrations are placed at the centre of the folio, albeit always as a framed insertion in the text, not in a panel separated from the text.]. From examples from Pooh[6This manuscript was erroneously identified as Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā in an article (Allinger 2006). It is in fact the first volume of a Śatasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā text.] (Kinnaur, Himachal Pradesh./India, Volume I of a Śatasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā / Yum chen mo manuscript in the Translator's temple) (Fig. 3) and now Dolpo it is clear that there were established traditions, at least for the first and last pages. On the first page there is a large image at both the left-hand and right-hand margin, and the intervening panel with text is often richly inscribed in silver or gold on a dark ground; in many cases the title of the text is written in large characters (Fig. 4). The Pooh manuscript constitutes an exception to this rule: the verses on the first folio command the reader to approach the text - the true teachings of the Buddha - with attentiveness and respect. The last page with the colophons often bears detailed images of donors and their families; in Indian palm-leaf manuscripts donors are mentioned in the colophon but not depicted as a rule.[7The Sam Fogg Gallery in London has a fragment of an Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā manuscript written in the 30th year of the elapsed reign of Govindapāla (c. 1191 CE). On Folio 216v - the penultimate folio - small, rather carelessly drawn donor figures can be made out flanking the central figure of Vajratārā; two male figures on the left and three female figures on the right (Losty 2008).]

Fig. 3 |

Fig. 4 |

Connections between image and text can occasionally be established on loose folios. Luczanits (2010: 574) has already pointed out that the story of Sadāprarudita is illustrated on manuscript folios in Tabo Monastery (Spiti, Himachal Pradesh/India). We are grateful to Gudrun Melzer for alerting us to the fact that the image on one folio (Fig. 5) not only represents Sadāprarudita and the merchant's daughter and her retinue venerating a book lying on a stand and the preaching bodhisattva Dharmodgata, but that there is a reference in the text to Chapter 75, the Dharmodgata Chapter, of the Śatasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā. However, the issue of the numeration of the chapters remains to be investigated, as the canonical versions of the Śatasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā have different numbers of chapters.

This story of Sadāprarudita recounted in the final part of the Prajñāpāramitā texts can also be found at Dolpo (Fig. 6).[8Folio 320 of the volume Nga N363, the colophon page of Chapter 76 (the last chapter) of a Pañcaviṃśatisāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā text, shows Sadāprarudita cutting the flesh from his calf while being observed by the merchant's daughter in the right-hand panel (Heller 2009, Fig. 106). In the case of Fig. 106 the correct folio number 320 is given. The detailed images are incorrectly labelled 'folio 247' (personal communication from Amy Heller).] In Tabo Monastery the whole story is illustrated in the ambulatory of the 'du khang, (Figs. 7, 8) showing that it was popular not only in India[9Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā manuscript in the Boston Museum of Fine Art, Acc. No. 20.589, Harriet Otis Croft Fund. (Kim 2008).] and Nepal[10Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā manuscript G.4203 in the Asiatic Society in Kolkata (Melzer & Allinger 2010).] but also in the West Tibetan region (Luczanits 2010).

Fig. 6 |

Fig. 7 |

Fig. 8 |

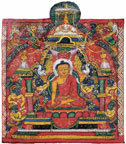

Fig. 9As examples for various treatments of one and the same pictorial subject there follow comparisons of images representing the Māravijaya.

In the Pāla manuscripts this is one of the Eight Great Events in the life of the Buddha, and like the other seven is only formulaically indicated; i.e., the Buddha displaying bhūmisparśamudrā stands for the Victory over Māra and Enlightenment. The Eight Great Events as a whole are a symbol for the life of the Buddha (Fig. 2).

Fig. 10In Nepal there are many more narrative details in the images of the life of the Buddha in manuscripts or on book covers. The Events are represented as multi-figured scenes (Fig. 9). However, this gives the Eight Great Events a completely different significance: in this case they are to be understood as providing a narrative to the life of the Buddha. They can be expanded with additional events or illustrated singly, as for example in the Nepalese manuscript of the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā from the year NS 268 which is preserved almost completely in the Asiatic Society Kolkata (G 4203). Two illustrated folios (Folios 133v and 134r) from this manuscript are held in the Museum für Asiatische Kunst in Berlin (Nos. I 5410 und I 5411).[11A detailed description and analysis of the illustrations can be found in Melzer & Allinger 2010.] In this manuscript Māra's assault on the Buddha is illustrated as the only Event from the life of the Buddha on Folio 133v (Berlin I 5410) (Fig. 10). Māra himself is not shown, but only four of the demons he has sent out, two of them shaking the throne and two blowing horns to disturb the Buddha.

The situation in the Tibetan miniature painting is again different. The images on the first and last folios measure approximately 10 x 15 cm and are impressive in their variety. The images on the first folio of the Pooh manuscript show Māra's assault on the left and a Buddha Assembly on the right (Fig. 3). Māra's assault is narrated in its various stages: (Fig. 11) at bottom left Māra attacks with bow and arrow; beside this is the earth goddess, (Fig. 12) while above them are demons and grotesque, wind-blowing faces with puffed cheeks. At bottom right are four figures grouped in two pairs, representing Māra's two daughters in the different stages of their appearance, first attempting to seduce the Buddha then after he has changed them into crones (Fig. 13).[12In the texts on the Māravijaya three daughters of Māra are mentioned, but the number varies in Indian and Nepalese representations. Examples of the latter include two stelas from eastern Bengal discussed by Bautze-Picron (1992 301ff) displaying multiple images of two daughters of Māra (stela in Kamalapuri Monastery in Dhaka and the stela Inv. A 22349 in the Indian Museum at Kolkata), and a Nepalese book cover (British Library, belonging to Mansucript Or14203, Zwalf 1985, 114 and 117) on which the Buddha is depicted flanked by two daughters of Māra.] Although the image is intended to represent a sequence of events, it initially gives the impression of a coherent group in an imaginary space containing only the rocky throne with viśvavajra and the Bodhi tree, placed like theatrical set-pieces.

Fig. 11 |

Fig. 12 |

Fig. 13 |

Fig. 14 |

Fig. 15

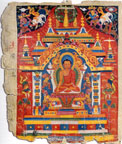

Fig. 16In Folio 304 of a Śatasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā manuscript from Volume Da N235 in Dolpo[13This folio is designated Ka within Volume 235, whose folios bear the designation Da. In this case Ka is evidently not the volume designation but part of an additional numeration, as frequently found at Tabo (Steinkellner 1994: 125f). Amy Heller (email of 16/2/2011) comments: "Ka is now an indistinguishable second letter. Beneath it both of the letters being on the edge of the leaf itself in the margin beside the numbering written in letters as gsum ....bzhi which here is clearly gsum brgya bzhi in terms of the space for the letters. This leaf is very important because it is the only one which shows the two letter system of numbering. In Steinkellner's description of the Tabo library, already he indicated the system of two letters --- In the manuscripts I have studied in ISIAO, the numbers for 301-399 are indicated with Ka wa zur, and I presume that this was the case here although now it is not evident."] the depiction of the Māravijaya on the left-hand side of the last folio is similar to that in the Kolkata manuscript but contains some essential changes (Fig. 14): not only is a greater number of figures depicted but the scene is given a wholly new significance by the precious shrine-like frame surrounding the Buddha. In Indian book illumination too figures are often placed within an architectural frame. While that latter initially displays similarities with built architecture, in the twelfth C it begins to assume the form of a decorative gem-studded or filigree metal (Figs. 15, 16) frame enclosing a sacred space. In the Dolpo manuscript folios it is not actual architecture that is being depicted; individual architectonic elements - richly set with gold and jewels - are assembled to form a precious shrine. The same tendency towards depicting sacred spaces rather than actual architecture is found in Western Tibet as well as in Pāla India.

Fig. 17The substructure of the throne consists of seven sections, each in a different colour probably intended to indicate various types of stone. On this rests the throne socle, consisting of five sections which are partially set with red and blue gemstones. In one section two lions facing outwards are depicted. From the upper edge a patterned length of cloth with borders is draped over the socle of the throne; it displays a vajra. On the socle rests the lotus throne proper which consists of a row of upright red petals. The nimbus and aureole of the Buddha are embellished with gold and jewels. The back of the throne is white and trapezoid in shape. Haṃsas are depicted on the outer edges of the throne back, and there are red and yellow scrolls around the nimbus and aureole. The throne proper is enclosed by an extraordinarily rich and ornate framing architectural structure. Two white columns - perhaps intended to represent marble - support a heavy superstructure. The decoration of the columns might be based on painting or possibly stone intarsia work. In the middle of the image on the right-hand side of the same leaf (two Bodhisattvas (Fig. 17), is a red column with three bulbous sections standing on a vase. The right-hand column in the Māravijaya image is very similar, but the intervals between the bulbous sections are covered with gold and blue petals. The same blue petals can be seen below the capital, only here they are widely splayed. The left-hand column stands not on a vase but a demon's head. In Indian stelas the arcuate superstructures above figures are also often borne upon columns or pilasters, but they are always reminiscent of built architecture, while here there is a clear relationship to artisanal craft objects. The pilasters bear a golden five-arched superstructure decorated with gemstones which protrudes laterally. On the side beams sit makaras, their tails forming large scrolls. In the centre of the arch is Garuḍa. The rest of the architectural structure as a whole has nothing to do with built architecture. Compared to the substructure, the spindly lateral beams and the superstructure are far too large and heavy, yet hardly stable enough to bear the stupa. In Nepalese manuscripts, notably on book covers, there are ornately decorated thrones and similar scroll motifs above the figure of the Buddha, but no such complex frames. The latter are most likely to have evolved in connection with painting and craft objects but - as is evident from the Tabo folios - could also have adopted individual motifs from built wooden architecture (Figs. 18, 19).

Fig. 18At the centre within the architectural frame the Buddha sits on his lotus throne displaying bhūmisparśamudrā with his right hand. As in the Kolkata manuscript four demons are depicted, two trying to shake the throne and two blowing horns. Outside the frame are two other airborne demons who are making a din by clashing their cymbals. The shrine stands against a red background decorated with a stylised pattern of blossoms[14This motif together with many others is very similar to those found in Folio 1v of the Ga N262 volume and Folio 354 of the volume Ga N400 from Dolpo. It is possible that these manuscripts were created in a workshop by various artists, as Heller has already surmised (illustration in Heller 2009 Figs. 81 und 87). Particularly striking in this regard are the decorative cloths draped above the figure of the Buddha which are found in both folios.]. The bodhi tree can be seen in the upper centre of the image. To the left and right are spandrels containing depictions of Māra and his cohorts against a black background with the same pattern. Two almost mirror-image four-armed demons hold bows and arrows together with a large boulder. Also on either side is a demon riding on a panther, together with conch shells. The right-hand spandrel additionally contains the head of a demon spouting water, and a snake. Arrows are aimed at the Buddha from both spandrels in an almost ornamental pattern and each spandrel also contains a depiction of Māra riding on a white elephant. By and large it would seem that these images - like those of the Nepalese manuscript - were based on the Lalitavistara, which contains a very detailed description of the army of Māra with all its many and various demons and creatures.

Fig. 19In connection with the depiction of Māra two articles by Claudine Bautze-Picron (1996 and 1998a) should be mentioned in which she points out that both the importance and appearance of Māra underwent significant change. The motif of Māra riding on his white elephant Girimekhala in his assault on the Buddha only occurs in the Nidānakathā, a Pāli text that was predominantly known in areas that practised Theravāda Buddhism. Nonetheless, Māra is frequently depicted riding on an elephant, even in regions that were certainly unfamiliar with the Nidānakathā. On the other hand, other criteria such as the adoption of Hindu deities in narratives recounting the life of the Buddha were important. The Hindu gods Brahmā and Indra are always present at the Buddha's birth and the descent from the Trayastriṃśa Heaven. As Bautze-Picron has established, from around the turn of the millennium other Hindu gods are incorporated into the descriptions of the life of the Buddha. The most significant and probably earliest occurrence of this is on the stele at Jagdishpur/Bihar, where Māra is sitting on the elephant together with Pāñcaśikha, Indra's companion. Both figures hold a vajra which on the left they are aiming at the Buddha and hold against their chests as they depart on the right, saluting the Buddha. "In both parts they are profiled towards the right, entering the composition in an aggressive mood in the left part while departing and acknowledging their defeat in the right part. From being the chief of the demons, Indra/Māra has thus turned to be a peaceful and mastered god" (Bautze-Picron 1996, 123). Depicted on the left below Indra/Māra are Śiva mounted on a bull and on the right Brahmā and Viṣṇu.

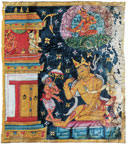

Fig. 20Thus, from this example and many others, mainly from Bengal (Bautze-Picron 1996), it may be concluded that it is not Māra but Indra that is depicted. Arriving from the left, he holds in his raised right hand a blossom (a transmuted rock?), while on the right he raises both hands in salutation to the Buddha after losing the fight. Māra is usually depicted in mourning after his defeat (Fig. 9). Here one can see the same transformation as described by Bautze-Picron for Jagdishpur. The blossom in Indra's hand at Dolpo indicates that the artist was not altogether certain about the figure of Māra/Indra. This is even more apparent in Folio 1 of a Śatasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitiā manuscript in Dolpo (Vol. Ka N52) (Fig. 20). There the same scene is depicted but in a far simpler form and a more vernacular style. Both the Māra/Indra figures are shown in a pose of veneration; evidently the artist failed to understand the narrative constraint for depicting this figure in different ways.

Fig. 21In formal terms the Dolpo depiction seems hieratic and almost timeless, an impression prompted by its strictly symmetrical composition. The temporal sequence can only be constructed from the various different depictions of Māra/Indra. However, there are at Dolpo parallel depictions of the Buddha displaying bhūmisparśamudrā and surrounded only by Bodhisattvas and disciples (Fig. 21) or even on his own. The victory over Māra is missing, and thus also any kind of narrative component. The precious frame and the symmetrical composition resemble the composition of thangkas, that is, images that serve for veneration and a deepening of contemplation. They are the central subject of Tibetan painting. The following sections will explore the genesis of these architectonic framing structures.

Sacred spaces in the medium of painting[15The topic was further elaborated in an article by Christiane Kalantari (in preparation b).]

A characteristic and innovative feature in Western Himalayan Tibetan art is its distinctive treatment of architectural representations in different media. The depiction of a Buddha Assembly on the right-hand side of the frontispiece of the Śatasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā manuscript at Pooh is one of the early examples of this tradition featuring a Buddha assembly in an elaborate throne (Fig. 22) (ca. early 12th C). We find here an accumulation of various architectural themes consisting of a throne and a palace-like structure.

Fig. 22 |

Fig. 23 |

Fig. 24 |

Fig. 25 |

The Buddha is encircled by an aureole in rainbow colours and seated on a (wooden) throne[16The wooden throne is comparable to those depicted in the wall paintings of the Nako Lotsawa lha khang.]. On this throne rests a multi-tiered palatial structure. The upper levels of this structure are topped by a pitched roof with sheltering eaves, and the whole is crowned by an āmalaka and a finial. This light, airy structure mimics certain elements of built architecture seen in wooden temples in the region, such as roofs and pilasters, but transforms them into elements of great decorative value. The ornamental qualities are further enhanced through the representation of material culture and luxury art; the gold on pastiglia relief mirrors a parallel development in the wall paintings of the region, notably the paintings of the Nako Lotsawa lha khang (Kinnaur, Himachal Pradesh/India) (Figs. 23, 24). The style of the manuscript can best be compared with folios recently rediscovered at Khorchag Monastery (mNga' ris, Tibet Autonomous Region, PR China) (Fig. 25), which show a sacred space filled with light using luminous and vibrant colours; the use of gold is further evidence of this tendency.

Fig. 26 |

Fig. 27 |

Fig. 28 |

Fig. 29 |

On the lowest register of the main (west) wall at the Nako Gongma temple (lha khang gong ma) - below a mandala which covers the wall above - a comparable celestial palace theme can be found featuring images of the Eight Great Bodhisattvas (Fig. 26). The bodhisattvas dwell in a row of multi-tiered palaces of various shapes linked by massive pilasters forming separate compositional units. In the centre of this ensemble is a depiction of Tārā as protectress against the Eight Dangers being venerated by the local elite. One of these architectonic units features a bodhisattva sitting beneath a multi-lobed arch (recalling the gavākṣas or horseshoe-shaped arches that decorate Indian temples and shrines) set in front of a temple (Fig. 27). The inner frame partly takes up the theme of the rainbow aureole. The innermost celestial abode of the deity is filled with light, represented as an aureole and a nimbus encircling the body and the head respectively. The lotus throne on which the god is seated appears to be growing out of a lotus pond that constitutes the background of the whole composition. The palaces consist of superimposed recesses of diminishing width, with towers, shrines or stupas[17Similar tiered structures can be found at Lalung, where they are crowned with stupas in which a Buddha image dwells (cf. Luczanits 2004: fig. on p. 97), and at Dolpo (Heller 2009 Fig. 77).] at the top, including perhaps also dormer windows. Some of the palaces have smaller shrines positioned on the edges of the lower recesses.

Fig. 30 |

Fig. 31 |

Fig. 32 |

Fig. 33 |

A comparable theme of linked celestial palaces with a Buddha at the centre can be found on the entrance wall of the Tabo 'du khang, albeit rendered in a much simpler form (Figs. 28, 29).[18However, the latter displays interesting features reflecting ritual practices such as the decoration of shrines with pearl bands and bells as well as the offering of streamers tied onto the pilasters by devotees.] Depicted on the lateral borders are monks and bodhisattvas paying homage to the Buddha, recalling the Buddha Assembly on the Pooh frontispiece folio, as discussed below. In contrast to Tabo, the palaces at Nako have a stronger architectural character and constructive logic, recalling sacred architecture represented in the art of the Indian subcontinent and in contemporary Indian book art, particularly that from Bihar and Bengal.[19While this type of śikhara or shrine-like architecture is used on the late ca. 9thC doorframe at Ribba for the main deities and in the Tabo 'du khang for the central Buddha, thus indicating a hierarchy, in later phases it appears in representations of different iconographic types.]

Fig. 34 |

Fig. 35 |

Fig. 36 |

Significant commonalities between individual motifs in Western Tibetan celestial palaces and Indian shrines or śikhara structures can be observed (Fig. 30).[20Bautze-Picron (1998b) was one of the first scholars to define the elements of Indian shrine depictions and trace their evolutionary history in Tibetan art. Some of these characteristic transformations of the Indian models are also to be observed in early (ca. 13th-C) Tibetan thangkas (ibid. figs. 1-2).] The commonalities are best studied at Nako; among the most characteristic elements here is the combination of pilasters bearing multi-tiered palatial structures. At Nako massive pilasters rest on bases recalling pūrṇaghaṭa crowned by capitals with volutes (Fig. 27). Among the characteristic decorative elements on pilasters in India are rhomboid shapes with foliate ornamentation, also executed as triangles (cf. Bautze-Picron 1998b: Fig. 41). These motifs 'travel upwards' at Nako, where they crown the pilasters between the temples; in this transformed use they recall constructive elements in Western Tibetan architecture, namely triangular or pediment arches that mimic wooden elements as well as typical pent roof structures exhibited by temples in Kashmir (Fig. 31). The idiom of the latter was also transferred to ornamental shrines or 'blind niches' (Fig. 32), as first observed by Romi Khosla (1979: 34-35; fig. 14).[21Romi Khosla (1979) presented a genesis of the motif of trifoliated arches in combination with gable roof motifs from Kashmir to Ladakh.] The engaged pillars on the first upper level are also significant. Together with the main pillars with bases recalling overflowing vases, they mimic wooden architectural ornamentation in the region, one comparative example being the richly carved pediment arches alternating with triple pilasters and ornamental features such as vases (pūrṇaghaṭa) carved in deep relief on the wooden elements of the Alchi Sumtsek's veranda (Figs. 33, 34). The pitched roofs crowning the different levels at Nako (Fig. 35) can be also traced back to wooden temples in the region (including Baltistan) and in particular in Kinnaur (both in Buddhist - such as the early temple of Ribba - and Hindu temples, one example of the latter being Chini in Kinnaur: Fig. 36,).[22Ceiling planks organized in a radial pattern and decorated with textile depictions are further indications that this type of roof system had a long tradition in the region (cf. Mañjuśrī lha khang, Alchi c.1200; Padmasambhava temple, Nako c. 14th C.).] At Nako they appear to be covered with coloured tiles;[23This was first suggested by Di Mattia 2007:65.] however, it is possible that these might be intended to mimic the stone slabs which are a characteristic building material those regions. The second upper roof level of one shrine is crowned by a characteristic āmalaka, which is treated here - in contrast to its Indian prototype - as a purely decorative element, whereas the rows of petals together with characteristic rows of appendages recalling wooden pendants[24Originally these were functional elements that conducted rainwater from the roof to the ground, thus protecting the façade of the temple.] between the different levels are closer to their models.

Fig. 37 |

Fig. 38 |

Fig. 39 |

A consistent element in Western Himalayan art is the rich use of textile motifs: in Indian shrine depictions they originally adorn the cushions of the throne and also decorate the cloth that is draped over its base at the front. At Nako decorative elements deriving from textile art fill the spaces between the different recessive levels of the superstructure (Figs. 37, 38).[25Interestingly, this tendency is also found at Pagan, as already noted by Bautze-Picron (1998b: 34; Fig. 26).

The constant interest in textile patterns in throne depictions preserve the memory of the vajrāsana, the seat of the Buddha's Enlightenment set up in the time of Aśoka Maurya, and is thus part of the long and enduring tradition of the uniconic representation of the Buddha.] This decorative system recalls actual architecture in the region (Fig. 39). The great variety of textile depictions and their careful rendering are typical of that style and also provide evidence for the offering of sumptuous garments to the temple by pious donors as well as their ritual use in the attiring of Buddhist temples. The donation of precious textiles as a central component of Buddhist ritual practice is also shown in donor depictions portraying the local aristocratic elite at Tsaparang (Papa- Kalantari 2007). The Tibetan Western Himalayan ornamental style reflects the transfer of symbols and values from the culture of luxury and status of the local royal elite to aristocratic and decorative features in the medium of art designed to portray the deities residing in sacred spaces of colourful splendour.[26The same textile motifs can be found on the ceiling at Nako Gongma and even in depictions of mandala palaces on the side walls of the early temples at Nako (Fig. 40). Some of the panels show depictions of printed cotton cloths and luxurious textiles such as silk brocades, which also reflect processes of cultural and economic transfer along the trade routes. These features in the art of Nako clearly indicate the regional impact of the rich and diverse Western Tibetan culture.]

Another important element in the definition of sacred shrines is the aspect of devotion and sensual interaction with the holy image on the part of the devotee which is reflected not only in the textiles decorating the different storeys but also in the depiction of ropes of pearls and bells hung on the shrine in which the Buddha dwells at Tabo (cf. Fig. 28).

Fig. 40The depictions of the Eight Bodhisattvas on the main wall display an ambivalent approach toward pictorial space: the sacred realm of the deities is defined by an illusionistic architectural structure as well as the two-dimensional hieratic throne frame. This artistic mode allows compositions that incorporate both temporal and spiritual space.

A slightly later date (12th C) can be assumed for a manuscript folio from Tabo Monastery (cf. Figs. 18, 19). Here a fusion of the shrine type discussed above and a stepped frame - its colour scheme alluding to an aureole - can be observed; the stupas on the corners recall local Tibetan architectural features also to be found in the throne representations in the Lalung Serkhang. The result is a simplified, abbreviated architectural space transformed into to a planar frame for the divinity.

To sum up: the representation of divine imagery in their sacred abodes shows a transfer of models rooted in the art of the Indian subcontinent; some elements of shrine architecture, as Bautze-Picron (1998b: 41) has rightly pointed out, acted in India as objects of iconographic value which were then transformed into decorative elements in later periods. While the overall architectural layout of the celestial palaces in Western Tibet takes up the tradition of the sacred images as replicas of the Holy Sites (in particular the Mahābodhi temple, where the Buddha experienced his Great Enlightenment), [27It was the premier site of pilgrimage, visited by great numbers of Tibetans, and many replicas were made of it and brought back to Tibet.] the ornamental details integrate local ornamental language and elements of luxury art specific to the region. In this way motifs of extreme visual complexity and colourful splendour are achieved. They represent not real architecture but rather sacred spaces designed to enhance the majesty of the deity residing within them. The artists integrated these elements, thus creating independent and innovative types of sacred spaces and styles of architectural ornament.

This type of Western Himalayan shrine is found as a significant feature both in wall paintings and manuscripts and in specific positions in the spatial layout, as will be demonstrated below, leading us to the question of its possible iconological function.

Sacred spaces and lay imagery in Western Himalayan painting

Fig. 41Another important independent feature of Western Himalayan book illumination and wall painting is the strong presence of royal and noble donors in the pictorial programme.[28In general, while in the early paintings in the Tabo entry hall (sgo khang) donor images represent a hieratic, ceremonial style, later images are more vivid, showing the ruling elite (perhaps of varying status) engaged in various actions and rituals.] Indian sculptures often feature representations of donors on the base shown as smallscale kneeling figures.[29Among the most famous examples are medieval bronzes from Kashmir: e.g. a Buddha from the Norton Simon Foundation (see Pal 1975: fig. 22a, b) and sculptures from Kurkihar/Nalanda - for example a bronze statue of the Buddha showing bhūmisparśamudrā in the Patna Museum (see Huntington 1984: Fig. 177).] In the art of Kashmir, Ladakh and Baltistan these depictions of lay persons commemorate the act of donation as a central form of Buddhist devotion. This tradition is continued in Western Tibet and features large-scale compositions which commemorate contemporary rituals and ceremonies. Portraits of the ruling elite even assume an important role in iconographic ensembles of religious imagery. In addition a synchronization of lay imagery and religious iconography can be observed on different levels (Kalantari, in preparation a). In the lowest zone of the Nako main wall discussed above donor depictions are placed below the central Tārā of the Eight Dangers in a mode of veneration, and they are additionally also engaged in a ritual (Fig. 41). The composition recalls a manuscript folio in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (M.81.90.6 for an image see Pal 1983: 123) featuring a Prajñāpāramitā and below a symmetrically arranged group of lay donors and a monk. The group is represented in an offering scene with ritual paraphernalia at its centre.

Fig. 42The presence of the local elite in religious imagery as part of the whole religious programme, and in relation to a specific thematic assemblage with didactic imagery in particular, is a characteristic feature of Western Tibetan art. The monumental assembly of the lay and monastic elite headed by the (lha bla ma) Ye she 'od in the Tabo Entry Hall is a paradigm case in this respect. By contrast, the dominant presence of donors is unknown in Indian manuscripts. Another specific feature in the evolutionary history of Western Himalayan donor depictions is the fact that the scenes become increasingly vivid, showing the ruling elite engaged in various actions reflecting actual rituals and historical events. They are often shown together with their families, or in genre-like scenes commemorating not only religious rituals but also different types of genre scenes, reflecting values of wealth and procreation and even echoing typologies found in representations of Indic tutelary gods (Kalantari, in preparation a) One of the most fascinating examples of this genre-like type of donor depiction is shown on the final page of a Prajñāpāramitā manuscript from Dolpo, featuring a female member of the noble clan depicted as a nursing mother; other genre scenes include for example a man spinning wool with a spindle (Fig. 42). Such scenes in different media of Western Tibetan art appear to provide a medium of self-representation for aristocratic donors in their striving for legitimacy and respectability vis-à-vis the local population and constitute a constant independent feature of this art. This reflects a religious landscape marked by the propagation of Buddhism by the royal and aristocratic elite. The programmatic text of the Pooh folio - which contrasts with Indian manuscripts in terms of both content and structure - is a further indication of the function of this type of imagery.

The frontispiece of the Pooh manuscript (Figs. 3, 22) is highly significant with regard to the form and function of donor depiction in Western Tibetan religious imagery. The assembly on the right-hand side of the folio shows a Buddha Assembly in form of a 'Sacred Conversation'[30This term was coined in connection with European Renaissance painting and generally shows the enthroned Madonna in 'conversation' with saints in a unified pictorial space; historical persons can be also be present in such compositions.] or gathering of protectors, the lay and monastic elite, crowned by an ensemble of Hindu deities above (among them Brahmā and Śiva). The text in the centre of the folio is significant by virtue of its unique content[31See the Appendix with the text and the presentation of the content.]. The text encourages the devotee to engage with the teaching of the Buddha (and with that of Prajñāpāramitā in particular) and to follow those who have attained perfect peace and joy through his wisdom. By virtue of its position at the beginning of the book, this combination of text and image - integrating the representation of the local elite - can be read as a conscious propagation of Buddhism in the region and as encouragement to follow the Buddha's path. This type of text appears to be related to didactic inscriptions in wall paintings.

Sacred ordering of space in a Western Tibetan temple

Fig. 43Interestingly the combination of the 'didactic' text and the Buddha Assembly or discussion scene found on the Pooh frontispiece recalls in certain ways a configuration in the entry hall (sgo khang) of the main temple (gtsug lag khang; c. end of the 10th C) at Tabo, which has recently been cleaned by the Archaeological Survey of India. There a non-historical inscription below the depiction of a Buddha - displaying the boon-giving gesture (varadamudrā) - is represented in the upper left-hand corner of the entrance wall (thus positioned at the 'beginning' of the temple's programme; Figs. 43, 28). The image of the Buddha together with the caption below accompanies a Saṃsāracakra (wheel of rebirth)[32Concerning the terminology used for the wheel, the Vinaya only uses the simple designation 'quinpartite wheel'. The term mainly used in the Tibetan sphere is srid pa'i 'khor lo, which stands for bhavacakra in Sanskrit (wheel of existences). However, we have chosen to use the term saṃsāracakra/'khor ba'i 'khor lo, wheel of rebirths following recent research by Schlingloff and Zin. Zin (Zin and Schlingloff 2007: 4) pointed out that the image of the water-wheel, alluding to the state of being 'driven' by a higher power, as a metaphor for the circle of rebirths and saṃsāra, is a constant feature in Indian religious literature. I also follow her terminology as the visual material on which Zin's analysis is based features the cave temples at Ajanta which share comparable decorative schemes to those in the entry hall at Tabo. I thank Gudrun Melzer for providing references.] as prescribed in the Vinaya (monastic regulations) of the Mūlasarvāstivādins concerning the decoration of Entry Halls.[33As has been shown by Schlingloff (1988: 169), the text next to the wheel of rebirths in the Buddhist art of Ajanta is from the Vinaya of the Mūlasarvāstivādin (MSV). The thematic ensemble also conforms to the instructions on how to decorate the entry hall of a temple in the MSV (cf. also Panglung 1981: 141; Zin and Schlingloff 2007: 22). Luczanits demonstrated that the MSV is also the source for the caption above the wheel at Tabo (Luczanits 1999: 115. cf.). The inscription on the entrance wall of the Tabo entry hall and the wheel of rebirth is also mentioned in Klimburg-Salter et al. (1997: 81).] The inscription was first transcribed and translated by Luczanits (Luczanits 1999: 115-116). The verses encouraging conversion to Buddhism (Vinayavibhaṅga, 31. Pātayantika, Q Vol. 43 73,1,6-2,4) read as follows: " 'Commence, go forth [and] join the Buddha's teaching! Destroy Māra's host, as an elephant [destroys] a reed-hut! Whoever conscientiously observes the [Buddhist] monastic rules (dharmavinaya) will leave the circle of rebirth, and reach the end of suffering' thus it is said." (Luczanits 1999: 116; translation following to a large extant the German translation in Schmidt 1989: 79.)

The text above the wheel of rebirth is related to the teaching of dependent origination and can be regarded through its connection with the Enlightenment as the quintessence of the teaching of the Buddha (Zin and Schlingloff 2007: 124-125).[34The assemblage of themes: saṃsāracakra, image of the Buddha and the accompanying caption - reflects one of the 'most essential tenets of the Buddha's teaching' (Bechert and Gombrich 1995: 28), namely the Chain of Dependent Origination resulting in the cycle of suffering and rebirth; a component of the Four Noble Truths expounded by the Buddha in the First Sermon after his Enlightenment (ibid. 1995: 49). The devotees entering the entry hall or veranda of the temple at Ajanta perhaps equated the wheel of rebirth with their own existence and contemplated the possibility of escaping from the cycle of rebirth, as suggested by Zin (Zin and Schlingloff 2007: 157).] Its intention in the temple is to encourage conversion to Buddhism and to follow the Buddha's path towards ultimate liberation. The thematic assemblage represented in the Tabo Entry Hall recalls the iconography in the veranda - corresponding to the Entry Hall of a monastery - of the vihāra-type Cave XVII at Ajanta featuring a wheel of life plus 'didactic' inscription, Avalokiteśvara as saviour from dangers together with local protectors (cf. for an image: Zin and Schlingloff 2007: Appendix).[35Positioned above the portal on the Tabo sgo khang entrance wall, between the wheel of rebirth and cosmological imagery, is a monumental depiction of Hārītī ('Phrog ma) and Pāñcika (lNga[s] rtsen); (Kalantari, in preparation a). As protectors of children and wealth - and also representing martial virtues, a constant feature in this region - they recall the role of tutelary deities charged with the task of protecting the 'mundane concerns' of the local population depicted in the veranda of the vihāra-type Cave XVII at Ajanta.]

As a contrasting feature at Tabo we find a monumental depiction of an assembly of eminent historical personalities together with laity and the monastic community on the side walls flanking the entrance wall. At the centre of the ensemble of historical personalities on the (south wall) is the portrait of Ye shes 'od, the founder of the temple (according to the Renovation Inscription), who - perhaps together with lo chen Rin chen bzang po - was the principal personality responsible for the re-establishment of Mahāyāna Buddhism in Western Tibet from the late 10th C onwards (a period which became later known as bstan pa'i phyi dar or the 'Later Diffusion of Buddhism').

Above the latter are Indic protectors in ensembles, while a local territorial deity (srung ma) denominated as Wi nyu myin and as protectress of the Main Temple in an inscription below (cf. Luczanits 1999: 114) together with guardians of the temple watch over the sphere leading to the main hall. The Tabo sgo khang (comparable to the early Old Entry Hall of Shalu/Central Tibet)[36While this strong presence of lay imagery is unknown in Indian art, it is a consistent feature in early Buddhist art in Tibet, e.g. in the old entry hall of Shalu (Zha lu; c. 1030).] is a singular early Buddhist example in the Western Himalaya where donors/lay persons and Hindu and Indic deities integrated as protectors into the sacred order of Buddhism dwell in an independent space as opposed to the sacred sphere of the mandala in the main hall.

The heavenly palace as border and interface

A related composition of a 'Sacred Assembly' is depicted above the portal of the chronologically later 'du khang (assembly hall) at Tabo, featuring a central Buddha (displaying dhyānamudrā, the gesture of meditation) attended by Avalokiteśvara and Samantabhadra and flanked by a community of monks above a local territorial deity, perhaps Dorje Chenmo (rDor rje chen mo) (Fig. 28). The placement of the latter above the door leading to the sacred sphere of the 'du khang appears to be significant.[37In the wall paintings of the Alchi 'du khang (ca. second half of the 12th C) the configuration or assembly of gods and humans listening to the Buddha's teaching is depicted on the wall leading to the sanctum - thus also in the entrance sphere of a mandala configuration. This position at Alchi is consistent with the hierarchy in the entry hall-main hall layout of temples in earlier phases (c. 1000). The theme of the Buddha Sermon placed above the Tabo 'du khang's portal (c. mid 11th C) is perhaps in certain aspects a reflection in condensed form of the older entry hall-main hall opposition displayed by the Tabo main temple. The older tripartite structure of the Tabo main temple appears to have been replaced by a more centralized spatial layout in the iconography from the mid-11th C onwards. This tendency is also evident in the design of later ground plans in the region.] In this depiction above the 'du khang's portal the Buddha is shown in a palatial structure flanked by the monastic community and gods, recalling the same theme depicted on the frontispiece of the Pooh manuscript. Although the Buddha images are shown displaying different mudrā in the book illuminations and wall paintings of this theme, they are related to central moments in his life when he discovered the chain of dependent origination that was the basis of his Enlightenment and thus the core of his teaching.[38It should be mentioned in this context - despite the chronological distance from Tabo - that the veranda of Cave 17 in Ajanta contains a depiction of a Great Assembly (mahāsamāja), in which gods from all regions and heavenly spheres came to be present during the preaching of the Buddha before his monks (Zin and Schlingloff 2007: 114). However, the MSV prescribes the Great Miracle rather than this image (ibid.).] Another little known example of the decisive iconological function of Sacred Assemblies is to be found in a monumental depiction to the right of the entrance wall of the Nyag temple at Khartse (mKhar rtse, rTsa mda' district, mNga' ris prefecture) featuring the Buddha within a large community of monks in Tibetan monastic robes. Therein historical figures are represented as direct witnesses of the teaching Buddha and they are thus perhaps conotated with the religious prestige of the first disciples of the Buddha.[39The image documented by Tsering Gyalpo (see: Tshe ring rGyal po and Papa-Kalantari 2009: fig 20) shows a large assembly of monks listening to the teaching of the Buddha, with one prominent monk to the left, most probably an eminent religious personality of that time associated with the foundation of the temple, and an interesting, and an interesting important small figure representing a bearded man in the lowest zone. He forms a bond between the world of the devotee, the onlooker and the monastic community. This unity is achieved both on a compositional level and in a symbolic sense. He is portrayed directly above the royal procession which has come to listen to the Buddha, and thus this person perhaps relates to the idea of the monarch retreating into a monastic order. See also an article by Thomas J. Pritzker (2008) who was the first to publish the Nyag cave temple.]

Fig. 44

To summarize, the motif of the heavenly palace as setting for a 'Sacred Conversation' has hitherto also been admired as a purely decorative element; however, such architectural themes have specific iconological functions. In particular the multi-tiered palatial structure marks a symbolically decisive border: it indicates to the devotee the path to the sacred realm of the teaching of the Buddha, a core element of the doctrinal system of that time; it is thus also a border and interface between the mundane and transmundane. The local elements in this type of shrine architecture signal that the guiding between these spheres can be provided not only in distant lands of the Buddha but also in the temples newly established by the local Buddhist elite in the land of snow. Accordingly, the portal of a temple, or the threshold between distinctive spaces in a temple are meaningful locations for this theme.[40One example being an image on the wall leading from the 'du khang to the sanctum or dri gtsang khang at Tabo; Fig. 44. In the earliest phase of decoration of the Tabo tsug lhag khang the entry hall appears to have had this function as border and interface, reflecting the horizontal tripartite hierarchy of spaces.]

The palace represented on the first folio of the Śatasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā (Yum chen mo) manuscript at Pooh is thus also a portal to the sacred sphere of the Buddha. Accordingly, the frontispiece of the manuscript can perhaps be regarded as the spatial equivalent of the ordering of space in a temple which is a unique feature found only in Western Himalayan book illumination.[41When reading the text the devotee is thus also present in a virtual sense in a world ordered according to Buddhist precepts. While such temple depictions are found on the frontispieces of manuscripts or on the entrance walls (Tabo) in earlier phases, they are later represented in the lowest zone of a complete composition, as found on the main wall at Nako. Accordingly, the rows of temples depicted in the lowest zone of the main wall in the Nako Gongma temple are not only decorative; they delineate and protect the space on the border zone with the mandala represented in the centre of this wall. Accordingly the eight bodhisattvas are also conceived of as guarding their respective direction. The palaces are thus also windows or 'gateways' to the sacred sphere, comparable to the verandas which are a constant feature in the spatial layout of Western Tibetan temples.]

The religious content of the space in which humans (lay and monastic personalities) and gods listen to the teaching of the Buddha, in both the temple - represented in the Entry Hall or above the portal - and at the beginning of a sacred book, is to create a cohesion between the local population, the monastic community and the world of the 'Enlightened One'.[42This space represents a border zone between the worldly and the sacred realm. In addition, the division of the (public) entry hall and (sacred) main hall perhaps reflects specific cultic needs: while the first appears to be mainly a place where the devotee performs ritual offerings (which is still the case, as noted by Christian Jahoda, verbal communication, 2.2011), the latter is mainly dedicated to the liturgical ceremonies of the monastic community, and the devotee is not usually admitted while rituals are being performed. Buddha Śākyamuni flanked by devotees can also be considered in the Buddhist doctrinal system as a one of three Buddha manifestations, namely that of the fragile temporary body (nirmāṇakāya) of the Buddha, an aspect of the Buddha intended to instruct mankind. The iconological content of such scenes is clearly to propagate the teaching of the Buddha and to provide a place for the devotee at the 'entrance' of the manuscript or to the temple in order that he or she might meditate on the possibility of teaching.]

The study of the relationship between text and image and in particular of the spatial organization of lay imagery in Western Himalayan manuscripts is at present in its infancy. This preliminary study shows that parallel characteristics exist in both book illumination and wall painting. Accordingly, it is also relevant as regards questions relating to the spiritual programmes and sacred ordering of space in temples as well as to problems of chronology in Western Tibetan art.