| Ceramics

The earliest

ceramic shards in China were found in the remains of cave dwellings

dating to 9,000-10,000 years ago. Large quantities of pottery

- mainly utensils for daily use - were unearthed in Neolithic

archaeological sites.

Covered jar |

The impact

of the invention of pottery on prehistoric man was enormous. Household

goods were essential to sedentary life, consolidating settlement

and helping to store agricultural produce. The diverse types of

pottery from different periods and regions have been classified

by scholars into four categories: red, gray, black, and white.

In 4000-2000 BCE, the firing temperature for pottery wares of

the Yangshao culture was so high that the clay burned red after

firing. The Majia Kiln culture was mainly distributed in Gansu

and the northeast of Qinghai. Ceramic manufacture was similar

to that of the Yangshao culture, but had strong local characteristics.

Painted pottery was developed, using black to paint the designs

and floral decorations.

The custom of burying pottery in tombs was introduced in the Han

Dynasty. Funerary models were large in variety and quantity, ranging

from storehouses, stoves, wells, pigsties, and pavilions, to fields,

ponds, livestock, and other features of the economic and social

life of the time.

Pottery figurines used as funerary objects in

ancient tombs were popular in the Qin and Han dynasties, and up

to the Sui and Tang, gradually decreasing after the Northern Song.

In the Shang and Western Zhou period human sacrifice was practiced.

Later, figurines of men and women were entombed, gradually replacing

the custom of burying people alive.

Army of the First Emperor

in Xi’an |

Thousands

of life-size pottery figures and horses were fired for burial

in the royal tomb during the Qin dynasty, symbolizing the grandeur

of the emperor. The discovery of the Qin terra-cotta warriors

and horses in 1974 shook the world. Over 300 ceramic infantry,

cavalry, chariots, and soldiers were excavated in the Han tomb

at Yangjiawan, Zianyang, Shaanxi Province. Composition of pottery

figurines remained as it was in the Sui and Tang dynasties, including

figurines of heavenly kings, civil officials, guards of honor,

servants, and dancers. The various groups of ceramic figurines

covered with a glaze called ''three colors of the Tang" or

Tang sancai are especially radiant and grandly decorated. ''Three

colors'' actually refers to a wider range of colors. It denotes

earthenware covered with a lead-based glaze and fired at a low

temperature, using iron, copper, and manganese as coloring agents.

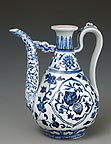

wine ewer |

Porcelain

is an invention of ancient China. Using porcelain rock or porcelain

clay as the basic material, it is fired at a high temperature

of 1,200 degrees C. Porcelain has a dense non-porous body and

a brilliant glaze. Abundant in variety, it plays an important

role in daily life. Already during the Shang and Zhou periods,

firing of primitive porcelain had emerged, while in the mid and

late Eastern Han period, true porcelain was developed. Porcelain

kilns are distributed in Zhejiang Province and other areas south

of the Yangzi River. The porcelain industry developed rapidly

in the Wei period, the Jin dynasty, and the Northern and Southern

dynasties, reaching high levels of craftsmanship. Celadon - stoneware

with a greenish glaze -was the most popular type of porcelain

ware, to which brown stippling and painted decoration were added.

The Tang dynasty porcelain industry produced two main ceramic

wares: ''blue of the south" and "white of the north,''

which is to say that the south produced mainly celadon and the

north produced mainly white-glazed porcelain. Porcelain flourished

during the Song and Yuan dynasties. Official kilns developed and

folk kilns began to emerge, forming different schools, such as

Ru, Guan, Ge, Ding, and Jun, honored as the five great kilns of

the Song dynasty. The Ding Kiln was famous for producing white

porcelain. The Jun Kiln fired red and blue glaze to achieve a

purple-red blend. The Cizhou Kiln is most renowned among the folk

kilns. It produced porcelain that used white as the base with

designs painted in black to create lively motifs in contrasting

colors. Blue-and-white ware is obtained by decorating the white

porcelain body with designs in cobalt blue, covering it with a

transparent glaze, and firing it at a temperature of 1,300 C.

Blue-and-white ware and other high-fired porcelains matured in

the Yuan dynasty, laying the foundations for the Ming dynasty

city of Jingdezhen in Jiangxi Province to become China's porcelain

producing center.

Porcelain technique advanced markedly during the Ming dynasty,

when a great number of new colors and shapes emerged. Potters

mastered the art of mixing metallic elements and firing them at

low or high temperatures to produce precisely the colors they

desired. As a result, a rich variety of fine porcelain works were

amassed. This exhibition traces the evolution of Chinese porcelain

art through the centuries, from its earliest stages and up to

its peak of delicacy and refinement.

Kong Xiangxing

Director, Art Exhibitions China

|