|

| Yoshitora "Image of Nihonbashi in Tokyo" (1871) |

The year 1868 was a turning point in the history of the Japan of the Shoguns. It meant the need to open its borders and adopt western models in order to modernize the country and enable it to compete with modern industrialized nations.

This assimilation of western models influenced almost all spheres of life in Japan: politics, economics, army, mores, social life, and of course, culture were testing fields for what the government called bunmei kaika (civilization and enlightenment). During the first two decades of the Meiji period (1868-1912) this process brought about what researcher Amy Newland termed a blind and unrestrained assimilation of western technology and culture. All things western were viewed as better, more advanced and preferable to things Japanese. The taste for western objects permeated the life of important cities such as Tokyo and Yokohama.

"It does not matter how commonplace many of these objects are today. There was a time when they were new and astonishing to Japanese eyes. The Meiji period is a spectacular case of cultural transplant and, at the same time, a unique contribution by Japan to today´s world"(1).

The changes that took place since the Meiji Restoration were swift, and culture could not let them pass by unnoticed. The world of ukiyo-e or, in the broader sence of the term, the traditional Japanese technique of woodblock printing mirrored these new events. The turn of the century was captured in these prints that were used as a means of communication at a time when newspapers had just started to appear, thus making available much of the information pertaining to this period, as well as many aspects of the fast modernization process unfolding Japan.

The interest for both western life style and western objects, was recorded as early as 1860 in the Yokohama-e (Yokohama stamps), where the European life style and the hectic trade at the various ports were portrayed with great detail and even ironically.

In this first period, artists such as Hiroshige III used the traditional techniques of the ukiyo-e to mainly represent modernization and life in the big cities . These prints maintain the characteristics of traditional xylography and reflect the ongoing changes in architecture, clothes and transportation in the country.

The architecture is one of the first elements of change highlighted by these prints. Alongside the traditional wood houses, brick buildings change the skyline of Japanese cities. It is rightly stated this "... was a period of public architecture. Most of the main edifices were built or financed by the government that deliberately tried to give the country a western look"(2).

|

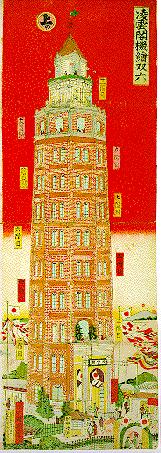

| Kunimasa "Internal and external view of the Junikai builiding" (1902). Fragment of a tryptic. |

Some of these buildings were portrayed in these prints: the Mitsui Bank; the Post Office Building; the British Legation in Yokohama; the Shinbashi Station; the 12-story high Junikai Building featuring amused people looking out of each of its windows (see illustration to left); the Nikoraido Church; the Akasaka Palace; the inauguration of the Bank of Japan, and others.

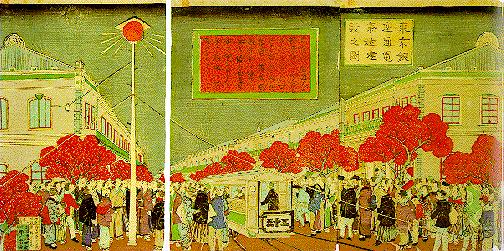

The new public spaces were also a source of inspiration for the Japanese artists of this period: Ginza Street, with its rows of trees separating the areas for vehicles from pedestrian lanes - an element that appears for the first time in Japanese cities, as do clocks, streets lights, paved streets and telephone poles.

Public parks, like Kozuke, the areas of Nihonbashi and Kyobashi with its bridges of stone and steel; the Asakusa neighborhood were the Junikai Building is seen near to the temple; the new factories and department stores are among the leit motifs of the ukiyo-e of this period.

Western means of transportation and clothes also filled these new spaces, where pleasurable promenades and fashions were incorporated to the public ambience. We see load carts, carriages and street trolleys drawn by horses, aerostatic ballons, the well known jin-rikishas, steam ships navigating past Tokyo, two-or-three-wooden-wheel bicycles rolling down Nihonbashi´s streets, colorfull steam engines, and Japanese people clad in western fashion: the ladies attired in rich lace dresses with ruffles, hats, shoes, umbrellas and handbags wearing make-up and European style hairdos, some of them walking their dogs; the gentlemen wearing suits, hats, cloaks and walking sticks, short hair cuts and mustaches, and even smoking cigars.

The creation of a parliamentary system and an army following the European model, military music bands, new symphonic orchestras, stores where canned products were sold, cinemas, national fairs, new industries, western sports, horse races, parties and banquets in clubs fashioned à la western and the circus, were some of the various aspects of social life that, together with the traditional elements of the Japanese culture, conformed a mixed panorama of the country´s capital towards the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th, portrayed by the Japanese xylography production.

|

| Sadakichi "View of the inauguration of the street lighting at Ginza street in Tokyo" (1884) |

In 1870, as a result of this tendency to reflect the country´s life, important Tokyo newspapers such as the Yubin hochi shinbun or the Tokyo nichinichi shinbun began to publish supplements in color. They were printed based on woodblock printing techniques and designed by the most prominent artists of the time(3), until technology replaced then with a more expressive and modern means: photography.

Together with this line aimed at portraying the country´s modernization through a traditional technique, developed a new trend within the ukiyo-e that began to integrate new elements of western aesthetics to Japanese printing.

The work of Utagawa Sadahide, an artist who worked the aforementioned style circa 1860, shows the integration of western stylistic elements, such as shadows and perspective, juxtaposed to the typical elements of the ukiyo-e. But it is not until the arrival of Kiyochika to the art scene that a mixture of these two aesthetics paved the way to a new sensitivity.

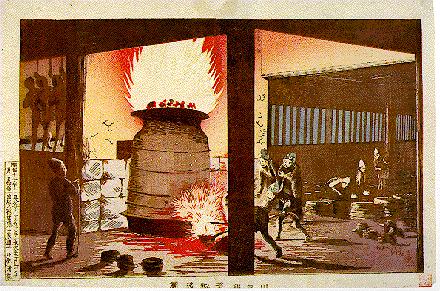

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847-1915) was the first to explicitly introduce European artistic codes combined with a peculiar Japanese view, thus creating his exquisite night scenes, where he played with lights and shadows with extreme care, giving these images a strong psycological atmosphere, an aspect almost absent in traditional woodblock prints.

Kiyochika enjoyed representing the mutating states of light: dawn and dusk, the reflection of gas light on the streets and on the water, and at the same time simulating, by means of xylography, the effects of other techniques such as watercolor and charcoal paintings.

Two of his many pupils (Yasuji and Ryuson) continued his line of work, which finally surrendered due the influence from new teaching centers like the Tokyo Technical School of Arts that gradually introduced the avant-guard language (Post-impressionism and Artistic Avant-guard) then in fashion in Europe.

It is at this time - beginning of the 20th century, ending of the Meiji period, with the Taisho period (1912-1926) in full swing - that a division takes place within the ranks of the ukiyo-e. The Sosaku hanga (Creative printing) shows up, deeply imbued in avant-guard experiments, and the Shin hanga (New Printing), a kind of neo-traditionalism that incorporates themes and techniques of the traditional ukiyo-e with an innovative air.

With these two artistic trends, whose parallels in painting are found in the Yoga (Western painting) and the Nihonga (Japanese painting), the Japanese woodblock printing or ukiyo-e gets involved in the multiple languages and artistic trends that characterizes the (western) art of our century, leaving in the hands of these "revivalists", but above all, in nostalgia, those fresh and delicate women painted by artists like Utamaro and Kiyonaga.

|

| Kiyochika "A view of a melting pot at Kawaguchi" (1880). |

References:

1.- Sibuzawa, Keiko. Japanese culture in the Meiji era. p: 4.

2.-

Ibidem. p: 105.3.-

During the Chinese-Japanese war (1894-1895), stamps were the main source of graphic information on war developments.

Bibliographic sources:

Benton Minnich, Helen. Japanese costume. Charles E. Tuttle Co., Tokyo, 1963.

Genshoku ukiyoe dai hyakka jiten. Daishukan, Tokyo, 1980-1982.

Japan in transition. Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Tokyo, 1968.

Keizo, Shibuzawa (ed.). Japanese culture in the Meiji era. Vol. V. Obunsha, Tokyo, 1958.

Michener, James A.. Japanese prints, from the early masters to the modern. Charles E. Tuttle Co., Tokyo, 1972.

Neuer, Roni & Susugu Yoshida. Ukiyo-e: 250 years of a Japanese art. Gallery Books, New York, 1990.

Newland, Amy & Chris Uhlenbeck (ed.). Ukiyo-e to Shin Hanga. The art of Japanese woodblock prints. Magna Books, London, 1990.

Smith, Bradley. Japan, a history in art. Gemeni Inc., Tokyo, 1971.

Ukiyoe daikei. Vol. XII. Shueisha, Tokyo, 1976.