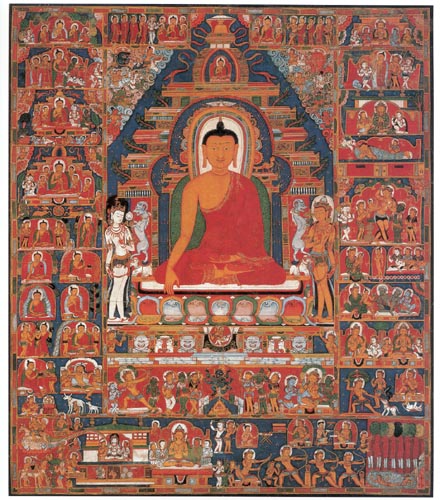

| 27. Scenes from the Life of the Historical Buddha

|

27.

Scenes from the Life of the Historical Buddha

Central Tibet, ca.

late 13th-early 14th century

Distemper on cloth

69 x 60.5 cm (271/8 x 237/8 in.)

Private collection

|

This painting depicts scenes from the life of Shakyamuni, the historical Buddha. Although no single authenticated

account of the Buddha's life survives, several Sanskrit texts are acknowledged as generally authoritative, among

them the Lalitavistara, the Buddhacharita, and the Mahavastu. These literary accounts inspired works of art

in which Shakyamuni's life was codified into four, eight, or twelve great events, although some narratives, as shown in this painting, include additional scenes as well.

Gautama Shakyamuni spent most of his life in eastern India, and some of the "great events" are associated with

particular sites where they are said to have occurred; for instance, the enlightenment is linked with Bodh

Gaya. As eastern India swelled with pilgrims between the ninth and twelfth centuries, imagery associated with the Buddha's

spiritual biography became increasingly popular, inspiring works of art not only in this region but

also throughout Buddhist Asia.

The central scene ( 1, see diagram, p. 116) shows the robe-clad Shakyamuni seated within the Mahabodhi

Temple; branches and leaves of the bodhi tree appear from behind the spire. His right hand is poised in the earth-touching gesture (bhumisparsha mudra), which is

associated with his victory over Mara (maravyaya) in an episode just prior to his enlightenment. Having vowed to remain in meditation until he penetrated the mysteries of existence, he was visited by Mara, a demon associated

with all the veils and distractions of mundane existence. Mara's menacing soldiers flank the temple's spire, hurling

weapons and making threatening gestures (1a). The Buddha remained unmoved by these assaults and by all

the subsequent distractions, both pleasant and unpleasant, with which Mara sought to deflect him from

his goal. According to some accounts, Mara's final assault consisted of an attempt to undermine the bodhisattva's

sense of worthiness: by what entitlement did he seek the lofty goal of spiritual enlightenment and freedom

from rebirth? Aided by spirits who reminded him of the countless compassionate efforts he had made on behalf of

sentient beings throughout his many animal and human incarnations, Shakyamuni recognized that it was his destiny to be poised on the threshold of' enlightenment. In response to Mara's query, Shakyamuni moved his right

hand from his lap to touch the ground, stating, "the earth is my witness." This act of unwavering resolve caused

Mara and his army of demons and temptresses to disperse, and Shakyamuni then experienced his great

enlightenment.

The episodes in the painting's right border include Shakyamuni's conception during a dream in which his

mother, Queen Maya, is impregnated by a white elephant who enters her right side (2); his birth, in which he emerges

from his mother's right side, greeted by the gods Brahma and Indra (3); the visit of the sage Asita, who announces

to King Shuddhodana that his son and heir has been born "for the sake of supreme knowledge. ... Having forsakenhis kingdom, indifferent to all worldly

objects, and having attained the highest truth by strenuous efforts, he will shine forth as a sun of knowledge to destroy the darkness

of illusion in the world."1 In this scene (4), the aged Asita is shown twice, once as he makes his

prediction seated before King Shuddhodana and the infant Shakyamuni and, a second time, while collapsing in grief as he realizes that because of his advanced age he will not

witness the great spiritual flowering of the infant sage.

King Shuddhodana recoiled at the thought of losing his heir to religion and made every effort to shield him. The

scenes in the painting's bottom registers describe the young prince's life within the palace, his existential

awakening, and his subsequent departure from the palace at the onset of his spiritual search. He mastered the arts of

writing and recitation (5), and swimming and archery (6). He captured the heart of his wife, the beautiful Yashodhara, in an archery contest, probably the one depicted in the scene in which the young prince is observed by young women as he steadies his bow (7). His

existential awakening is sparked by four excursions outside the palace: He encounters old age (a man leaning

on a staff [8]); sickness (a man lying on the ground, wrapped in a blanket [9]); death (a body tied with a black

band [10]); and a religious mendicant, the seated monk seen here (11). Troubled by the inevitable and apparently senseless fate of all men and

women, Shakyamuni vowed to free himself from the cycle of birth, sickness, old age, and death by apprenticing

himself to ascetic practitioners. He left the palace under cover of darkness, accompanied by his faithful

charioteer Chandaka and his horse Kanthaka (12); removing his crown (here, secured on Kanthaka's back) and other ornaments,

he sent them back to his father's palace.

The left register records events associated with Shakyamuni's austerities, his enlightenment, and his first

teachings, as well as the miracles associated with his ministry. The cutting of his hair (14) signals the

beginning of his period of asceticism. He refused to yield to the craving of his

senses and even to his need for

bodily sustenance, which brought him to the point of starvation. Young boys who came upon him in meditation

prodded his ears with sticks, thinking he was dead (15).2 Shakyamuni ended his austerities when he recognized that

sensual deprivation was as much a hindrance to spiritual awakening as was the sensual indulgence he had enjoyed

as a prince. From a village girl, Sujata, he accepted a bowl of rice cooked in milk (16). Shortly afterward, Shakyamuni

made a seat for himself under a pipal tree at Bodh Gaya and vowed to remain seated in meditation until he

experienced profound liberation (1). After his enlightenment, he remained in meditation for seven full days; he was protected from violent storms by the serpent king Muchalinda, who wrapped himself around the

Buddha to form a canopy surrounding the Buddha's head (17).3 Having emerged from his meditation, the Buddha was

persuaded by the gods Indra and Brahma that others would benefit from learning of his experience. Careful to

indicate that he was not to be regarded as a savior but merely as a guide, he gave his first sermon in the deer park at Sarnath, where five ascetics, who had once been his

companions, became his first disciples (18).

During Shakyamuni's long ministry his disciples reported many miracles, a few of which were incorporated

into an established iconography. The first of these is the Miracle of Shravasti, also known as the Miracle of the

Twins (19). This episode involved several miraculous events, including the Buddha's creation of a double who acted as interlocutor, posing questions that the Teacher answered before avast

assembly.4 Soon after the miracle at

Shravasti, the Buddha ascended to Trayatrimsha Heaven to preach to his mother and the gods, descending months later by a

bejeweled ladder (20). Other miracles include the gift of honey from a monkey (21) and Shakyamuni's taming of the

mad elephant Nalagiri, sent by his jealous cousin, Devadatta (22). Remarkably, the last great event in the

Buddha's life- his death (mahaparinirvana) - is the only major event of his spiritual biography omitted in this

work.

It is interesting to compare this painting with a twelfth-century Tibetan painting of the same theme in the Zimmerman Family Collection.5 Many of the episodes are similarly rendered, although the present work includes additional scenes not represented in the Zimmerman painting. Moreover, in the Zimmerman painting, the Buddha's life is rendered in an Indian guise the costumes, architecture, and other aspects of the imagery closely follow Indian models. In this work, however, the palaces are based on Tibetan architecture, and the royal robes resemble those worn by the early Tibetan kings. The painting may be compared with the thirteenth-century painting of Amitayus in this exhibition (cat. no. 29), with

which it shares many iconographic features, including temple spire, throne setting, and standing attendant

bodhisattvas. The somewhat more perfunctory treatment here suggests a later phase of this style, probably toward the end of the thirteenth or during the early fourteenth

century. JCS

1. From the

Buddha-Karita of Ashvaghosha; see Cowell 1969,

pp.10-14. [back]

2. Although in this rendition Shakyamuni's body appears

unchanged, during this period of his life the Buddha is sometimes portrayed as an emaciated, skeletal figure, most notably

in Gandharan art. [back]

3. Literary accounts of this episode vary; some state that

Muchalinda protected the Buddha during his third seven-day meditation after enlightenment. See Cummings 1982,

p.175. [back]

4. One might expect to see two Buddhas in this scene, but the

iconography here appears much as it does in other works, as Susan Huntington has observed, in Seattle

1990, pp. 104, 188, 316. [back]

5. Published in New York 1975, no. 3; Seattle 1990, no. 107; and

New York, Himalayas, 1991, no. 81. [back]

|