Asianart.com

| Exhibitions

The Theyyams of Malabar

Catalogue

While most Western images of India still have an awestruck voyeurism to them, British-born photographer Pepita Seth has achieved a rare accomplishment - she has managed to see the country with local eyes.

Gallery of Pepita Seth's photographs

click on small images for full images with captions

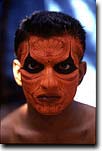

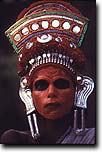

A man sits on a wooden stool tentatively holding a small club-like object. His naked brown torso and face are suffused in white, the result of a special powder made out of rice. He is wearing a pleated red skirt-like garment cut into several layers, and on top of his head rests a spectacularly huge red and gold headdress. His eyes are submerged in black kohl, his lips are painted a bright crimson, and a large circle of red graces his forehead.

But, that's not all you see in Pepita Seth's photograph of Velutha Bhootham or "white ghost," a part of her collection of pictures about an ancient performance ritual in southern India where some men, after appropriate mental, physical and spiritual preparations, supposedly "become" divine beings for a short period of time, and are worshipped by the community.

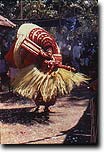

A few feet away from this "deity," a young man, with just a plain piece of cloth wrapped around the lower half of his body, looks entirely uninterested in the extraordinarily adorned man. His legs are casually spread apart, his hands lightly enfold a wooden pole, and he seems to be staring at the tree nearby. You can see the trace of some spilt liquid on the ground between him and the deity.

The fantastical and the real, the exotic and the ordinary, the extravagant and the simple, all seem to merge seamlessly in British-born photographer Seth's work, which focuses exclusively on Hindu rituals in India's southern state of Kerala. While her subject might be the ultimate exotic, her direct approach to towards it, her emphasis on giving the whole picture and not just the sensational and the dramatic, lends a unique down-to-earth flavor to her photographs.

"I have fought hard not to represent exotica in my work," says Seth, whose exhibition titled Reflections of the Spirit: The Theyyams of Malabar was on display at the Dialectica Gallery (soon to become Culture Gallery) in New York City January and February, 2001.

Unlike the gaping voyeurism common to many Western pictures of the East, her photographs look like they have been taken by an insider, which is, in a way, exactly what she is. She has lived in India for over 20 years, spending a great deal of that time in Kerala, living with and like the people of the region. Surviving primarily on the magnanimity of the local people, she has dwelled in the houses of different families (free of charge) for periods that range from a few weeks to several years.

"Oh, I have a bad reputation for showing up and still being there years later," says Seth, quite unabashedly, explaining that the people treated her like a member of their families.

"Does a daughter have to ask if she can stay in her own home is what they said to me one time when I sent them a letter asking if I could stay," she says, referring to a family she stayed with from 1979-85, the time she lived full-time in Kerala.

A curious blend of the East and West, Seth, born Pepita Fairfax, is a slender, gray-haired woman in her late fifties, who is as comfortable in the Indian sari as she is in jeans and a sweater. She insists she is "a fish out of water in the West," but there is no mistaking that clipped British accent or that sharp sarcasm. She has nothing but disdain for the English-speaking, post-colonial world of New Delhi, India's capital city, but feels completely "at home," in rural Kerala, where English is barely spoken.

The daughter of upper-class landowners, Seth grew up on an isolated farm in Suffolk, England with no company except the peasants who worked on the land, and yes, she insists, there was not even one friend there during her childhood.

"The only people I ever had to interact with were the people who lived on the farm and in those days, unfortunately, because I am quite geriatric now, the people were much closer to the land, in a mythical sense, than they ever are now," she says. "And through these people I was party to what spirits lived under what trees and things like that."

In her late teens, she left home for the bright lights of London, where she worked as a film editor on commercials and documentaries. A fortuitous discovery of her great-grandfather's diary account of India in the mid-nineteenth century brought her to the country for the first time in 1970. That two-month long trip was followed by several longer ones before she actually moved to Kerala in 1979.

"It's like falling in love," she says of her relationship with the state known for its coconut trees and sandy beaches. "I had a very insecure childhood and they gave me a sense of space and place. Also, there was something there that connected with my childhood. When I first went there, the look was different, the temperature was different, the food was different, but basically I was dealing with something I had known since my childhood, that is the spirit world. Nothing is ever overt though, it's just understood."

It is her affinity to the extraterrestrial that attracted her to the multifarious Hindu rituals of Kerala, which she has been photographing for almost three decades. Not ambitious in any conventional sense, she lived in Kerala with a sort of hippieish attitude - she wanted to "hang around" and take photographs.

Seth's first exhibition was held in a Hindu temple in 1981 and she had her first commercial exhibitions in Glasgow and London in 1997. A book of photographs that she took on Hindu rituals in general is due to be published in England next year, and she is hoping to get a contract for another book on the Theyyam ritual, the subject of her most recent exhibition.

While her first exposure to this unusual ritual was in the mid 80's, she didn't become seriously engaged with it until about 10 years later when the myth of a goddess associated with it (that she refuses to tell) inspired her to go to Kerala's northernmost region of Malabar and dig deeper into this little-known tradition.

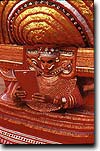

Although most Indian Hindus do worship gods and goddesses, the uniqueness of this ritual lies is the fact that the deities are embodied by men, who dress up and enact the myth of the divine being they are supposed to be, with the community giving them paltry monetary offerings as a sign of devotion. It is believed that the performer enters into a trance and actually "becomes" the deity, with the transference of consciousness occurring when the fully-costumed man looks into the mirror and sees not his own made up face but a reflection of the deity.

A fear of being mocked coupled with the inability to explicate the inexplicable has made Seth extremely guarded about talking about her intense fascination with the ritual that has been an endless wellspring of creativity for her.

"Some people view Theyyam as a spectacular form of entertainment and it's not," she says. "It's an act of worship and I respect the divine spirit."

The myths of the deities, spanning every aspect of the human condition from rage and violence to repentance and forgiveness, have a powerful cosmic spirituality, which is very different from the Christian vision.

"Christ is always compassionate, you never see another aspect of him," she says. "But there is violence in life, there is terror in life and you can't tidy it up by separating the good from the bad. Early Christianity tried to clean up the act and pretend you had to be one or the other. So much in the Western urbanized world of today, it's all nice-nice. With Theyyam, you're dealing with a primal power. Nobody's fudging it."

Seth's relationship with the performers/deities, most of whom are from the lower rung of the caste hierarchy, is extremely close, and she gets very irritated if you try to ask a naïve question such as what they are like.

"What do you mean?" she says. "They have two arms and two legs."

It is precisely that sensibility that gives her work its characteristic matter-of-factness and non-exotic quality. In contrast to many Orientalist artists, she never intensifies the more sensational or "other" aspects of scenarios - a big tongue sticking out of a mask, kohl-drenched eyes, silver fangs - to create a striking effect. Many of her photographs are taken in broad daylight and you can see the trees, the gravel and the twigs crystal clear in the background. In the Theyyam collection, her frequent inclusion of people besides the deity in the photographs - a person helping him dress up, onlookers, a hand helping to prop some part of the costume up - give her work an air of reality it might have otherwise lacked. Also, she uses no flash and does not manipulate the photographs after they are done, accentuating the naturalistic effect.

But, she is extremely hesitant to think of her photographs as "art" in the traditional sense of the word, saying that her work is not really the pursuit of an individual vision.

"I am, in fact, suppressing my ego," she says. "I am fairly invisible and just try and show what is there. Who am I to impose myself on these rituals? What I have attempted to do is take the photographs they (the people in Kerala) might have taken."

|

text

© Priya Malhotra and Asianart.com

images

© Pepita Seth