Asianart.com || The Legacy of Absence || Exhibitions

INTRODUCTION

![]()

by Sarah Stephens

|

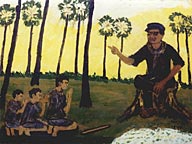

(This article first appeared in the Summer 2000 issue of Persimmon: Asian Literature, Arts, and Culture www.persimmon-mag.com Copyright © 2000 by Contemporary Asian Culture, Inc. All rights reserved.) An imposing Khmer Rouge commander sits in the lotus position on a rock, his right hand raised in the air in an unquestionable gesture of authority. Below him, on the ground, three small figures kneel in supplication, their hands held reverently in a sampeah, listening to the commander's words. The figures are primitively drawn and the detail rough, but the message is clear. The Khmer Rouge are the new religion, the usurpers of Buddhism. Across the gallery, a similar message is portrayed, but with a more menacing edge. On a towering canvas, the great machine of Angkar (the name the Khmer Rouge gave to their regime) is depicted in violent, clashing colors. The mechanical giant looms above the spectator, its legs tucked underneath itself and its six arms raised elegantly in a theological parody. But this is no benevolent god-in its hands are hoes, rakes, and other agricultural tools, all dripping with the blood of its victims. The artists who have depicted these scenes are no trauma-voyeurs

or bloodthirsty thrill-seekers. They are survivors of one of the twentieth

century's most legendary and cruel regimes, the Khmer Rouge. Over a

period of nearly four years, through their Mao-inspired agrarian revolution,

Pol Pot's Khmer Rouge struggled to return Cambodia to "year zero,"

to eliminate the bourgeois, the capitalists, the educated middle class,

and all other enemies of the state, including teachers, monks, writers-and

artists. "I know what happened during this time," says Phy Chan Than, who did the painting of Angkar. "I made this picture because I want all the world, especially Khmer descendants, to know about the Pol Pot time." Chan Than's massive, semiabstract canvases are unusual in Cambodia. Today most artists here follow a strictly commercial and unchallenging career path, choosing to paint saccharine images of Angkor, the spectacular and revered ancient temple complex that forms such a major part of Khmer consciousness, or soft-porn images of seminude women bathing in waterfalls. Chan Than, now a professor at Phnom Penh's University of Fine Arts, trained in Hungary when Cambodia was a communist state; the composition and colors in his paintings have a distinctly Western feel. "Most of the students who come to the exhibition to see my paintings cannot understand the abstract images," he says. "Some of them even refuse to believe that they were painted by a Khmer artist." One of his canvases, The Koh Tree, a wildly colored abstract, carries a detailed explanation beside it on the gallery wall, to help spectators understand the artist's intentions. In Khmer, explains Chan Than, the word for the Kabok tree is "koh," which also means "mute." During the Khmer Rouge era, an oft-repeated saying had it that, "If you want to live, plant a koh tree in front of your house." In other words, keep quiet if you don't want to die. "We had to remain silent about everything we saw, knew, or heard," says Chan Than. The Legacy of Absence exhibition in Phnom Penh includes the work of ten artists, and several of the works shown there will form part of a much larger, worldwide exhibition on the same theme, tentatively scheduled to open in May 2002 at Buchenwald Memorial, near Weimar, Germany. American art-lover and entrepreneur Clifford Chanin created the Legacy Project, a U.S.-based foundation, in order to draw together artists from countries that have suffered mass national traumas or genocides, leaving a great "absence" among the populace. Among the countries to be represented in the worldwide exhibition are Germany, Israel, Japan, China, Bosnia, the former Soviet Union, India, and Pakistan. "The idea of the exhibition is to try to understand the kinds of things that are missing after a mass murder or war, and to explore whether there is a way to fill the emptiness that the victims leave behind," according to Chanin. Many of the countries approached for the exhibition already possessed a vast collection of genocide- or trauma-related works, but the organizers encountered an unusual problem when they approached Cambodia for exhibitors. "The only art works you ever see in Cambodia are the mass-produced paintings of Angkor," says Ly Daravuth, co-curator of the exhibition and one of the artists whose work is included in the show. "When you talk to the artists who produce them, they say they only want to produce beautiful things, that above all, their art should show beauty." Amazingly, there were almost no paintings of the Khmer Rouge regime by Cambodian artists before the Legacy exhibition was organized, even though the regime collapsed over twenty years ago. Many artists cite political fear as an overriding reason for not producing such art, but Daravuth thinks there may be a deeper reason. He believes that the absence of such a body of work is almost as powerful a statement as if the work had been created in droves. |

|

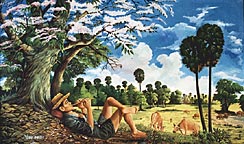

"The people just refuse to confront

it so far," he says. "The artists do not want to contemplate

it; it is too hard. Sometimes when you have a shock, you don't want

to talk for a while. They just want to look back with nostalgia, and

so they cling to these Angkor paintings." Daravuth himself is a survivor of the Khmer Rouge years. As a young boy in the border camps of Thailand, he helped his uncle, Ngeth Sim, also an artist, prepare canvases. Sim was sent to France as a refugee, where he has lived ever since, but some of his paintings are being exhibited for the first time in Cambodia in the Legacy show. The Last Look is a deeply disturbing sketch of the artist's father just before he was led to his execution. Painted in deep hues of magenta and blood red, the canvas shows five emaciated, semi-naked men, resigned to death, their spirits completely broken. Four have their eyes fixed on the ground, but one, wearing glasses, turns to look sadly over his shoulder. "My poor father, at the moment when the Khmer Rouge led you away, I fixed on your face intently," writes Ngeth Sim. "I did not have the force to protest in front of these torturers, to prevent them from taking you and killing you. . . . Dearly beloved father, I pray every night that your soul will pardon me." One of the few exhibitors who had created art depicting the cruelty of the regime before the Legacy Project approached him was Vann Nath, one of Cambodia's leading contemporary artists. Nath was one of eight known survivors of the notorious Khmer Rouge detention center, Tuol Sleng, in which around 16,000 men, women, and children were systematically tortured and executed. Now fifty-four years old, he is the only one of those eight survivors who is still alive today. He is best known for his series of paintings made in 1980-81 depicting his time as a prison painter. (Because of his artistic abilities, he was forced to spend his time in prison turning out portraits of Pol Pot.) Today, Nath, a distinguished and gentle-looking man, whose shock of thick white hair makes him stand out amongst the rest of his countrymen, lives quietly in Phnom Penh. He paints very little now, but acknowledges his unique position as sole surviving witness of Tuol Sleng. Yet his eyes darken when he speaks of his time at the center, and although he granted an interview for this article, he rarely talks to journalists. "It was very hard to make those Tuol Sleng paintings," he said of the 1980-81 series. "I felt like I was living through it all again." His work in the Legacy exhibition stands in stark contrast to many of the other bleak images. Nath chose to contribute a painting of an idyllic rural scene: a farmer relaxes under the shade of a tree and plays his pipe, surrounded by lush greenery and deep blue skies. "Ever since the war, the farmers have been afraid," he explains. "There are thieves, and there are land mines. I am trying to create a picture of the ideal, for the countryside to have freedom at its heart." He shyly acknowledges that the painting is a self-portrait, saying it is for his grandchildren. "I want them to know that I went through it all and I am still strong." "There has been too much suffering here," he continues. "Now I want to think about independence and freedom and beauty. I am always prepared to do my duty as a witness, but in art, I want to paint landscapes and beauty." For Cambodia, the very presence of such an exhibition is at least a small step forward in the healing process. Nearly every single family in Cambodia suffered losses during the regime, from starvation, execution, or disease; the final death count stands at around two million people. Part of the healing for those left behind is coming to understand how they can live with that "absence." "How do we deal with this heritage?" asks Daravuth, who admits that even though he lived through the Khmer Rouge years, he cannot get a full, coherent grip on what happened to him. "With heritage like Angkor Wat, you have conservationists, picture painters, and so on. But the Khmer Rouge regime can't be classified-like a UNESCO world monument-there's nothing there. You have to find another way." Sarah Stephens is a journalist who has lived and worked in Cambodia for three years. All

images and captions copyright © 2000 Reyum. All rights reserved.

Reyum Gallery Persimmon: Asian Literature, Arts, and Culture The Legacy Project |