asianart.com | exhibitions

Back to JWDC Exhibition

Introduction by Claire Burkert, June 1998

Artists associated with the Janakpur Women's Development Center are earning recognition as some of the finest contemporary artists in Nepal. This exhibit celebrates the life and work of these village artists, a number of whom joined the JWDC when it was initiated in 1989. To date, their work has been exhibited in the U.S.A., U.K., the Federal Republic of Germany and Belgium. The artists' pleasure in the development of a profession, and in the new-found freedom to express themselves through painting, is reflected in the stories they tell in these pages.

The paintings are rooted in traditions which Maithil women have passed down through generations. On the occasion of marriage or for festivals such as Deepawali, Maithil women paint lively designs on the mud walls of their houses. During Deepawali, in order to attract Laxmi the goddess of wealth, they paint designs of elephants and peacocks which symbolize prosperity, as well as images of tigers, birds, and other animals. In monsoon season the paintings fade or wash away.

The paintings are rooted in traditions which Maithil women have passed down through generations. On the occasion of marriage or for festivals such as Deepawali, Maithil women paint lively designs on the mud walls of their houses. During Deepawali, in order to attract Laxmi the goddess of wealth, they paint designs of elephants and peacocks which symbolize prosperity, as well as images of tigers, birds, and other animals. In monsoon season the paintings fade or wash away.

Janakpur is now famous for its colorful paintings on paper, yet this "tradition" began in the first days of the JWDC when, under a grant from the Ella Lyman Cabot Trust, a talented group of women were selected to learn how to transfer their wall designs to paper. They travelled from their villages to the Center in Janakpur where, without losing their originality, they developed skills in composition as well as in the use of color and line. After various experiments, it was decided to paint on Nepali handmade lokta (daphne) paper which had the rough texture of mud walls. Then, after trying pens and sticks, the women decided on brushes, and after experimenting with their own dyes and pigments which they mixed with milk, they found that acrylic paint worked best on Nepali paper and could be used as spontaneously as the dyes and home-made paints applied to house walls. And so it was that the JWDC created both the form and medium of what is known today as "Janakpur painting".

The first show of the artists' works on paper was held in 1990 at the American Library in Kathmandu. It was just after the People's Movement which established democracy in Nepal, and with the new democratic spirit this first show of Maithil art from southern Nepal received warm welcome. The artists gained support from the United Nations Development Fund for Women, as well as other donor agencies, and both their organization and their art began to flourish.

The first show of the artists' works on paper was held in 1990 at the American Library in Kathmandu. It was just after the People's Movement which established democracy in Nepal, and with the new democratic spirit this first show of Maithil art from southern Nepal received warm welcome. The artists gained support from the United Nations Development Fund for Women, as well as other donor agencies, and both their organization and their art began to flourish.

There was by then a strong core of women, most of whom were illiterate, and who had never taken part in any kind of organization. They loved coming to the "office" in Janakpur, a comfortable and supportive environment with women of many backgrounds, free from the constraints of the village. Through being associated with a development project they were soon making paintings promoting Vitamin A, the chance to vote, safe sex and saying "no" to drugs. Proud of their traditional culture, they continued to illustrate Maithil rituals or to make paintings of gods Ram and Sita who, according to legend, married in Janakpur. And in the "office" where they sang songs or told tales of the Hindu gods, they naturally painted scenes from the Ramayana or from Maithil songs and folktales. Many women have enjoyed painting the Maithil tale of Anjur, a tale in which a new bride is made to do impossible tasks by her jealous sisters-in-law, and each time is helped by sympathetic birds or snakes. They often mix images of other tales with Anjur's tale, and similarly Gods will appear in scenes of family planning. This mixing of themes is a reflection of the real world of the Janakpur artists today.

Anuragi is perhaps the most unusual of the JWDC's artists. She is a Brahmin woman in her late fifties, uneducated, highly religious, and a renowned traditional storyteller. Each day she strolls into the JWDC barefoot, carrying a bag of offerings from her trip to the temple. Then she sits down to paint and concentrates intensely. Usually she is fasting so she naps during lunch. With her energy restored, she again focuses as if she were creating a mandala. Her paintings contain all her spiritual rigor and excitement. She fills the space completely, unifying all the elements of her painting, and seems to love this process. Integrated in the finished painting may be Hindu gods and family planning methods, or vegetable vendors and visits to the doctor.

Galo began her career as an artist with a repertoire of three images: a peacock who smoked a water pipe, a smiling tiger with scales, and a pair of pregnant elephants. Gradually she wanted to try her hand at other things. Today she often likes to paint what she sees or hears about: a woman visited by ghosts or a scene from a Hindi movie. But while the subject matter of each artist continues to change, the individual character and style of each of the painters is never lost. Sita, Mithileswari and Phuliya, all artists of the Kayastha caste, incorporate the style of their caste in their non-traditional paintings, often borrowing images found in specially-decorated Kayastha wedding chambers-the sun and moon, parrots, fish, bamboo and lotus. Suhagbati paints sturdy people who look like herself, and her paintings are well-constructed, with box-like houses and buses, and bold colors filling in areas of space. In sum, what distinguishes the master artists of the JWDC is their individuality: when you become familiar with the paintings you do not have to look at the signature to identify the artist.

Anuragi is perhaps the most unusual of the JWDC's artists. She is a Brahmin woman in her late fifties, uneducated, highly religious, and a renowned traditional storyteller. Each day she strolls into the JWDC barefoot, carrying a bag of offerings from her trip to the temple. Then she sits down to paint and concentrates intensely. Usually she is fasting so she naps during lunch. With her energy restored, she again focuses as if she were creating a mandala. Her paintings contain all her spiritual rigor and excitement. She fills the space completely, unifying all the elements of her painting, and seems to love this process. Integrated in the finished painting may be Hindu gods and family planning methods, or vegetable vendors and visits to the doctor.

Galo began her career as an artist with a repertoire of three images: a peacock who smoked a water pipe, a smiling tiger with scales, and a pair of pregnant elephants. Gradually she wanted to try her hand at other things. Today she often likes to paint what she sees or hears about: a woman visited by ghosts or a scene from a Hindi movie. But while the subject matter of each artist continues to change, the individual character and style of each of the painters is never lost. Sita, Mithileswari and Phuliya, all artists of the Kayastha caste, incorporate the style of their caste in their non-traditional paintings, often borrowing images found in specially-decorated Kayastha wedding chambers-the sun and moon, parrots, fish, bamboo and lotus. Suhagbati paints sturdy people who look like herself, and her paintings are well-constructed, with box-like houses and buses, and bold colors filling in areas of space. In sum, what distinguishes the master artists of the JWDC is their individuality: when you become familiar with the paintings you do not have to look at the signature to identify the artist.

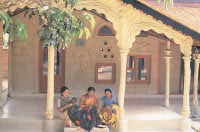

The artists now work daily at the Janakpur Women's Development Center. It is a beautiful complex which the members decorated with traditional mud relief designs. The artists share ideas and images with women working in other sections of the Center who produce ceramics, textile, and papier mache. Over the years they have also received training in literacy, management, planning, gender awareness, health and child care. For them, painting is synonymous with a new social life with women friends from different villages and castes, and some of the stories they typically share are recounted in the next pages. My hope is that this exhibit will help to create a greater understanding of the Janakpur artists, as well as a new interest in how their art evolves.

The artists now work daily at the Janakpur Women's Development Center. It is a beautiful complex which the members decorated with traditional mud relief designs. The artists share ideas and images with women working in other sections of the Center who produce ceramics, textile, and papier mache. Over the years they have also received training in literacy, management, planning, gender awareness, health and child care. For them, painting is synonymous with a new social life with women friends from different villages and castes, and some of the stories they typically share are recounted in the next pages. My hope is that this exhibit will help to create a greater understanding of the Janakpur artists, as well as a new interest in how their art evolves.

asianart.com | exhibitions