Asianart.com

|| Exhibitions

Foreword || Colors of Ink

|| Main - Paths of Ink || Introduction

Musée Guimet

June12th to September 10th, 2002

INTRODUCTION by Philippe Koutouzis

|

Contrary

to the generally held belief, Chinese painting has never ceased to evolve.

At the various stages of its growth, individuality and respect for tradition

acted together or in opposition to produce countless treasures and innovations.

The example of T'ang Haywen, in the second half of the 20th century,

illustrates this phenomenon particularly well. T'ang never received

any formal education in art apart from learning calligraphy from his

grandfather, T'ang Yien. In Paris, he acquainted himself with the work

of western artists and chose to become a painter. Art was a way of life

for him, not a career choice. Already faithful to tradition, his work

bore the mark of true individual expression as well as a sincere detachment

from material contingencies. His work revolved around landscapes as

subjects and ink as his medium. T'ang assimilated the underlying principles

of Chinese painting that had regarded ink as the paramount medium since

the end of the 9th Century. Many terms describe the wide range of its

applications: splashed ink, broken ink, po mo, which uses accents

of darker ink to break the wash, cun, texturing brushstrokes,

yi pin, unrestrained painting, da xieyi, expressionistic painting.

Through constant experimentation in the medium, T'ang finds his own

path through ink painting, developing a personal trait by defining a

constant space for his pictorial expression. He painted in series, always

using standard sizes of paper or cardboard surfaces. This allowed him

to paint quickly and no longer concern himself with the issue of format.

It also bestowed upon his work a unifying consistency at the same time

as separating him from the painters of his generation. T'ang's artworks were produced on Kyro or Aanekoski brand paper sized 70 x 50 cm, or 100 x 70 cm, at first always in the vertical or portrait format. Later, he opted for the diptych configuration and turned to the horizontal or landscape format. He began with small diptychs of 29,7 x 42 cm which he used as studies for the forthcoming large-scale works; their size was convenient and suitable to a technique which was becoming increasingly spontaneous. By the end of the sixties, he had definitively adopted the large diptych configuration of 70 x 100 cm. The subtlety of the ink and water based colors suppresses any tactile discrepancy between the blank and the painted areas of the paper, between the negative and positive space. The work recedes from the surface it is painted on; a relationship is established between the horizon of this broadened view and the line that divides the work into a diptych. This line coordinates and focuses the spectator's eye, that one might share the vision of the painter.

Another characteristic feature of T'ang's works lies in the calligraphy of his signature (p.147): It combines Roman letters to Chinese ideograms which for T'ang acts as a metaphor for his life and his work. In Chinese, the literal translation of the word signature is print of the heart, or the essence of the being. Usually painted in red, like the traditional seal, it becomes part of T'ang's composition. It is elegant, dynamic and conveys energy and substance. From Asia to Europe, he repeatedly returned to his tradition so as to enrich and modernize it. T'ang

is born in 1927, in Amoy, now Xiamen, an island located in the Formosa

Strait, along the Fujian coast, a province of Southern China. Amoy is

one of the ports that opens to trade after the Opium wars and falls

back into apathy when Hong Kong becomes the gateway to China. At the

start of the 20th Century, the island is still green and peaceful, basking

in the sunny climate of the tropic of Cancer. Time is running slowly,

paced by the Taoist calendar and the arrival of boats. The economy is

based on fishing, boat making, and the maritime trade. Every one has

a cousin or a brother striving to "make a fortune"

somewhere else in the world. Peking is far away and the Fujian look

out to the open sea. The islanders go to the great isle of Formosa,

now Taiwan, to visit relatives or sell goods. On several occasions,

T'ang escorts his father there. Like all Chinese children, he learns

by heart the words of the Daodejing, the book of the way

by Laozi. Superstition and devotion are found in many of the rites designed

to heal the sick, exorcise demons and honor ancestors or deities. Somehow,

every human activity is attached to a ritual. |

|

In 1937, when the war starts in Asia, T'ang's father takes his family to Cholon, the Chinese district of Saigon, in Indochina. This crossing is T'ang's first lengthy trip. Here is what he wrote to his brother thirty years later: "I remember stories told about my childhood. It seems that I used to get lost in the crowd, and perhaps, something inside is drawing me towards the unknown. I don't need the sense of security that appeals to others". Following his arrival, he joins the Southern Chinese Communities School and befriends a young girl named Ming Qing. In 1942, Ming Qing drowns while crossing a canal. This is the first tragic event in T'ang's life. One year later, he attends the French school in Saigon, as a serious and hard-working student. By this time, he is already drawing pencil portraits on the pages of his French-Chinese dictionary. Then, he also underlines a few words in red ink: peintre (painter), peintresse (woman painter), peinturage (peinturing), peinture (paint). His grandfather, son of a member of the imperial administration, is teaching him calligraphy according to the cursive script, the academic and regular standard. Suffering from asthma, T'ang sometimes has to rest and spends long hours reading books and newspapers brought to him by one of his teachers. At home he uses the Fujian dialect but at school, he speaks French, reads basic English and even learns some Japanese by the end of the war. His teachers suggest he should be sent to France to complete his studies, but his father, who is making use of his multilingual abilities in the silk trade, expects him to take over the family business. As in every other Chinese community scattered across Asia, people in Cholon perpetuate the Confucian tradition of a social order where passion is a plague, and the unknown is a danger. Incidentally, T'ang's Nickname is Kongzi, short for Confucius, referring to his taste for studying. He is, of course, determined to honor his family, but not as a merchant. He stands out from other teenagers, being more sensitive and more secretive. He is isolated within his community and at the same time open to the outside world when he can cross its boundaries. Through books, he may have already delved deeper into the contents of the Taoist philosophy that praises the individual as a founding principle of all harmony. He comes across as eccentric: remote from the center while still attached to it. In 1946, he writes his chosen forename on the flyleaf of his dictionary. The name associates hai, the sea, to wen, writing. His family circle wants him to get married and one of his father's business partners promises a large sum of money if he accepts to work in the shop for a year. At the end of the year, he is still yearning to go to France but his father categorically refuses. As a result, T'ang goes on a hunger strike and, after ten days of fasting, is at last granted permission to leave, on the condition that he should study medicine in Paris, and afterwards return immediately to Cholon. Once in France, T'ang attends Paris University and, in 1949, receives a degree in French Civilization with honors. He also attends French literature and Oriental language classes, and briefly attends medical school. In 1950, he begins to take some drawing lessons at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière and spends most of his time visiting museums and galleries. He teaches himself oil painting, produces portraits, still-lifes and landscapes in a figurative manner and applies the rules of perspective. The dexterity of his hand, trained by calligraphy, as well as a definite gift for observation enable him to progress quickly in mastering flat brush techniques and the composition exercises of western painting. Naturally, he quotes western masters and looks to his immediate environment for subjects. Even in the early stages, his creations convey a typically Chinese atmosphere and sense of space.

He produces nostalgic pieces about China, serigraphs and small watercolors on rice paper. He revisits subjects where the calligraphic line becomes more and more obvious. Around 1955, he paints several self-portraits including Self-portrait with cat (3), using a style reminiscent of his participation as an actor in the touring shows of the Antique Drama group of the Sorbonne. He travels to Epidaure, in Greece where he plays the part of the Coryphée in Eschyles' the Persians. Nicole Marette, then wardrobe supervisor, nicknames him Ariel "the good genie, exuding generosity and consideration towards others". Jacques Lacarrière, later to author L'Été Grec (the Greek summer), is also part of the drama group. T'ang loves meeting people, he makes friends from all backgrounds, but never mixes them. His first French friend, Raymond Audy said of him that "he spent most of his time exercising his freedom."

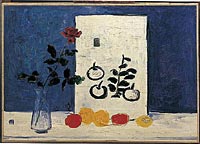

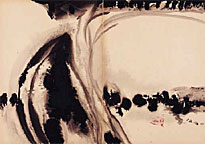

He continues to pursue his training as an artist. First, he adopts the objective proposal of the impressionists to describe an instant in Nature, then, Cézanne's subjective principle to show the instant in the eye of the painter. Cézanne's idea, a foundation for modern art, brings him closer to the Chinese theory that painting is an expression of the thoughts and feelings of its creator. The Still Life With Rose (4) painted around 1955, is characteristic of the evolution of his art. His integration of texture, color, and principles of physical reality, challenges the line, the essential means of description and expression in Chinese painting. Three methods are being used here: The pure color defines the physical reality of the fruits on the table. The line shapes the persimmons and the foliage located in the center. Finally, the rose is constructed in a combination of lines and colors that render reality. An oblique shift occurs between the rose and the center where the persimmons and the foliage compose an ink painting, a picture within the picture that translates the reflection of the painter. In 1964, in his Homage to Cézanne (6), T'ang imitates part of the composition of the Large Bathers from the collections of the Philadelphia Museum. However, the eroticism that transpires from it is closer to the Bacchanale, from the National Gallery of Art in Washington. The inspiration found by Cézanne in Rubens or Poussin matches his desire to create a type of art "as solid as the one found in museums" just as Manet before him, found the source of his Olympia in the Venus of Urbino by the Titian. T'ang himself plays the game of interpretation, or rather hijacking. Even though he adopts the pyramidal grouping of the figures, the slant of the trees and the game of transparencies, he parts the composition through its middle, unbalancing it, so setting it in motion. (See p.146) His bathers are not hieratic figures, they are exposed to our gaze in an unusual way for a Chinese painter. The swift making process using gouache, dry ink and wash, balances the shapes according to the Chinese tradition, on a diagonal axis. The succession of hues, from the most opaque to the most transparent, creates an atmospheric perspective that flees towards the light formed at the center of the picture by the bare paper. The shaping of the bathers still associates the texture of the gouache to the ink lines. Twenty years later, at the peak of his artistic maturity, T'ang paints an Homage to Turner (108) that reuses the palette of the 1840's works by the English Master kept at the Tate Gallery, in London. Incidentally, most of these paintings are kept hidden from the general public until the 20th Century. Turner himself was individualistic, he had discarded the lines and classical compositions to glorify light and shadow through the sole use of color, and he played a crucial role in the apparition of modern painting currents. Through this exercise, T'ang demonstrates the depth of his feelings, he breathes a typically Chinese fluidity into the seascape and pays homage to Turner's relationship to painting. He acknowledges his vision of the landscape based on the spirit rather than the form. Here, the idea precedes the artwork. The

1960's represent a shift in his work. Installed in Paris, in a small,

poorly equipped flat in the rue Liancourt, T'ang travels extensively

to the United States and through Europe, responding to invitations and

an urge to discover new places. On an almost daily basis, wherever he

is staying, he keeps a painted diary of the impressions triggered by

landscapes. By then, he has assimilated the western styles and even

if he is still using oil paints, he finds a greater freedom of expression

in watered-down gouache, watercolors and ink. This choice suits his

nature, he sees himself as a Taoist and practices painting as a way

of self-fulfillment. Some western observers have defined Taoism as a

natural mysticism in order to explain its influence over the arts by

comparison with other major cultures. Others have even coined it as

the true religion of China. The spiritual aspect of Tao is undoubtedly

central to Chinese painting. It conditioned its creative processes,

its subjects and their interpretation. The still life is replaced

by the expression of the living spirit of an object, a flower or a landscape

translated by a few brushstrokes, following a principle of tension between

opposite or complementary forces. There is no sun without a shadow.

The Tao brings life to the mountain and water, literally shansui

or landscape in the Chinese terminology. They possess an intrinsic nature.

The painter can see the spirit of the mountain and seize it before

it flees. This belief gives the painter a quasi-religious role of observer.

When it touches the extraordinary, no one can say whether Art is Tao

or Tao is Art. T'ang practices the kind of "self-renunciation" that Michel Serres, a Christian philosopher, identifies in the adult age: a withdrawal from strong attachments and material possessions, but within the consciousness of a vast universe reaching beyond any dogmatic dimension and that conceptualizes man as the meeting point of its energies. Man is a privileged observer of nature and can express Tao through the silent poems of painting. The attitude of T'ang is not one of severe asceticism - on the contrary, it cultivates the art of living in the present while avoiding the traps of reason. His distance, that could pass as arrogance for a westerner, allows the existence of divergence and contradictions.

Two large paintings dating from 1964, Men (7) and Birds (8), are produced according to this very principle: a chaos, or rather a nucleus of energy, unifies the composition of sprayed ink and color. In both works, men are represented as in ancient scripts. The void of bare paper occasionally covered by a transparent wash, strengthens the composition and eliminates all concerns of perspective. In Red Sun (12) the hatching and alternated brushstrokes tighten the space on the paper towards the horizon and progressively cover its bareness, creating an eminently Chinese perspective. Lines, stains and splatters cause the subject to vibrate. In Calligraphy (5, left) a head is topping what looks like a figure, thus inducing a literal meaning. What catches our attention, however, is the apparent improbability of the moving figure in a lunar atmosphere that implies stillness. In Calligraphy (28) T'ang places the character for man, rén, above the one for enter, rù. The character for man stylises the erected position of a human being, the one for enter originates from the drawing of a tree that stretches its roots through the ground. The universe balances itself between heaven and earth; between a visible, real world, where the tree is the lasting proof of life and a symbolic world with existential properties.

At the end of the 1960's, ink becomes prominent in T'ang's work. He revisits the more expressive works of the Song, Yuan and Ming eras as well as the more individualistic ones of the early Qing era. He finds both aesthetic and philosophical inspiration in the works of Shitao, a key artist of that time. Reading his Recorded Remarks on Painting, confirms the importance of the task and prepares the poetic grounds required for painting. The book also advocates the absence of a method. François Cheng, author of a renowned book on Shitao, holds some of his works as the very first abstract paintings. To clarify his position in relation to abstraction T'ang wrote: "I think that total abstraction is a dead end, only justified by theory, expressing itself through a fleshless verb… Painting can only evolve from some degree of concrete figuration. Thus, it can regenerate itself without losing itself and spread within the areas of affectivity and spirituality". T'ang paints what he sees; a landscape, a Dawn (50), a dusk, a Forest (83), a heat wave, waters, The Disc of the Sky (92). He has reached the stage of realization of his own art, now fully in control, and conveys a concrete but essential idea inspired by reality. The human figure has almost completely disappeared from his compositions; He does not feel the need to demonstrate, like his predecessors, the relation of scale between man and nature. Far from being a parable, his painting replaces what it represents. It gives the viewer an opportunity to share the feelings of the painter, as if like T'ang, his eyes and heart are open. Freed from influences, T'ang declares, in an interview: "I am trying to ignore the conscious world, to reach beyond it and explore new shapes, always linked to nature and its rhythms. I am trying to identify with Nature's forces and to materialize them through painting." The scale of the large diptych assigns a unique space to this expression, fully identifiable and enabling all kinds of experiments. In 1971, T'ang leaves for India with one of his painter friends, André Dzierzynski. In Goa, he meets Tom Tam, an American filmmaker, also from Fujian, who has traveled with his wife along the Indian Route. They spend a month in a fishing village where they shoot a 16mm short film called Furen Boogie, the Lady's Boogie. Two years later, Tom Tam goes to Paris and proposes to make an experimental film with T'ang's work. The 16 mm camera, that shoots 24 frames per second, can also work in stop frame animation, which means that single pictures are photographed consecutively. Tom and Haywen select and record continuous series of large diptychs, from the darkest to the lightest, from the fullest to the emptiest. They reverse the sequence, and alternate a short series of black shots with shots of bare paper and stills, lasting for a few seconds. The edited film, T'ang Boogie is amazing and probably one of a kind - sequence reproduced pages 138-139 -. The images flash by in a succession of short bursts like ink jets on paper. The white paper shots resemble sparks of light. The art works are shown as single size still frames, 48 images flash by within two seconds, forwards and backwards. The eyes get used to it, the brain memorizes and recognizes the images. The animated ink of T'ang Boogie, translates into reality the random paths of ink that echo life itself. This metaphor frees T'ang from the affectation of virtuosity and preciousness. He contributes to a process that is using his work as raw material. There, in accordance with the artistic ideal of Taoism, he finds a very contemporary resonance.

In the same way, Boogie illustrates the nature of his 1970's production. Some paintings, dominated by blank areas crossed by a few lines, alternate with other works where the space of the diptych is almost entirely inked, only revealing bright dots of blankness. In the landscapes, the marking of the vault of the sky (70, left) and the high horizon (93) stand as permanent features: wide strokes of dry or watered down ink, horizons in the Zen spirit, extremely stylized, such as Dawn (50), a true ink field. T'ang uses the round brush that renders every move of the hand; each line is personal and the permeable paper forbids any revision. He sometimes paints on a table and moves around it, or tints the sheets of paper, wipes some areas and resorts to masking devices. In reaching beyond the technique, he attains a theory that promotes exaltation and unruliness as the prime artistic attitude: in a painting or a calligraphy, the accidents or the drips are manifestations of vital energy. Parallel to large scale ink drawings, T'ang carries on painting small watercolors, landscapes (55), flowers or fruits (60) on rice paper whose colors can be quite strong. They do not counteract the ink drawings and even appear like a step in their direction. Around 1984, the inks become lighter and swifter, their structure comprises a wash punctuated by dots and lines, the landscapes are internalized, getting away from reality (114). T'ang qualifies this work as "figural" and constantly refers to nature. He uses Arches rag paper or Ingerois card to produce series of small triptychs in ink or watercolors and some imaginary portraits with clownish or tortured faces (110). During his life as a painter, T'ang exhibited his work often, but with no career plan; He went from a museum space to a regional council hall, responding to proposals and encounters. Although he made friends with major artists and curators, he continued, thirty years after Épidaure, to write to the most obscure of his acquaintances. He practiced daily the Taoist principles of production without possession and of action without self-assertion. He continued working as a painter and lived on his artist isle, accomplishing his task of 'transmitter of culture'. T'ang was the actor and the witness of a true evolution in the interaction between east and west. Until the 1950's, the west set the trends. The observers of modernity - seen as the true and living expression of the time, distinct from everything that had preceded it - looked down on the 'Asian copyists', whilst granting the utmost sensitivity to western artists influenced by Asia. At the time, the only known Chinese paintings, were academic pieces dating from the 19th century, contemporaries of our own pompier painters. The long line of artists who had practiced expressive painting in China remained totally ignored. They include: in the 12th and 13th Centuries, during the Song era, Mu Qi whose Six kakis belongs to the collection of the Daitokuji, in Kyoto, or Liang Kai and his Chan Priest from the Palace Museum in Taiwan; also in the 16th century, during the Ming era, the free expressions of Hsü Wei, who painted bunches of grapes with a few scattered dots; and finally those artists from the Qing era, in the 17th and 18th centuries, including Bada Shanren and Shitao, who qualified as eccentrics or individualists. When T'ang arrives in France, the post-war Paris art world is bursting with energy. People are talking of a new reality and of a future humanity. Édouard Pignon, a supporter of metamorphosis, is painting "trees portraits", Dalí mixes vegetation with human shapes, Germaine Richier creates ant-women from a combination of plant debris. Science and mechanization are condemned for what they have produced. More than ever people are trying to grasp the future, to represent it. Isn't civilization an illusion?

European

artists talk of landscape painting and naturalism, of intuition and

spontaneity. Soulages, who reads Shitao's Remarks, states that

black is the "symbol of a mystery yet to be revealed",

that it is the "means to create light, imposed by the shadow

that was generating it". In 1955, the Japanese Artist Morita

Shiryü teams up with Alechinsky on a film called Japanese Calligraphy

that explores the interaction between informal art and calligraphy.

The French critic Michel Tapié, who had fashioned the phrases

"informal art" or "tachisme", documents the Zen

tradition of sprayed ink. In the United States, the abstract expressionism

triumphs, Clement Greenberg can see in it the first purely American

modern movement. Unfortunately, he forgets to take into account the

Asian influence on people like Tobey, Reinhardt or the contribution

of the Asian-American artists. However, abstract expressionism and informal

art change the interactions between Asian artists and modernity. They

can no longer be accused of copying. They are skilled at calligraphy,

a painted form of writing that associates meaning and form. The Asian

painter is allowed to abstract it as he wishes and can shift freely

between calligraphy and painting. In a piece kept at the Musée

Guimet, reproduced on page 28, Hon'ami Koetsu (1558-1637) uses blue

paper, golden leaf and ink to convey the feelings inspired by the blossoming

cherry trees on the slopes of Mount Yoshino. In Mountain (9,

above), T'ang associates the calligraphic lines to the strong blue and

yellow hues. His outline evokes the Chinese character for cloud, yún,

written in cursive script, and reminds us of the magic writings of the

Taoist rite, sometimes called yúnshu, cloud writing. But

the work is concerned with form, in a primarily pictorial vision that

lets the viewer choose its poetic development. As early as 1911, Kandinsky was writing that creation needed the external condition of a clear, boundless way. Two centuries before him, Shitao, had rebelled against a taste for paintings that were only referring to the classical models of China. They both held freedom as essential to creation. Even if throughout their history China and Europe encountered similar aesthetic or ethical problems, their solutions differed. Nowadays, the art world is a closed up field where major forces clash in a market traversed by trends that were conceived for the masses. Artists no longer inscribe their work in a linear or progressive history, they must prove that they are producing art. Our thoughts are torn between a prolific doubt and a belief in the end of history; Other deadlines, other worries have surged and we seem to be on the verge of a new questioning. The great diversity of the contemporary Chinese art world is a consequence of its opening up to foreign influences. Immediately after the 1911 Chinese revolution, arguments between ancient and modern intellectuals, gave birth to schools and movements supporting or opposing tradition, ink and oil painting. Some painters left to study in Japan and later in Europe such as Pan Yuliang, Chang Yu, Zao Wou Ki or Chu Teh Chun. T'ang belongs to those who, whether through personal choice or the course of history, did not return to China. Today, their remote evolution, that lasted for many years, captivates a Chinese art world in the making. Once again, opinions differ on the Chinese identity of such artwork. The same piece will be regarded as Chinese by some because it was painted by a Chinese person or seen as too westernized by others to deserve this attribute. There is a renewed interest in ink and calligraphy that, even during the toughest episodes of 20th century's history, survived in China through the works of painters like Fu Baoshi, Qi Baishi, Cui Zifan, Zhu Qizhan or Chang Dai Chien but always in a naturalistic spirit, close to representation. Today, younger painters like Jiang Baolin, Zeng Mi, Yan Binghui or Yang Yan Lai combine tradition with modernity. Westerners are fascinated by Chinese culture and every trend that stirs China. Artists are selling their work abroad, new movements are rising that echo the tendencies and reflections of the international art world. In the last few years, large-scale exhibitions have approached the art of China from a historical angle. They include: A century in Crisis, modernity and tradition in the art of 20th century China and China: 5000 Years, organized by the Guggenheim Museum in New York; Others, like Asian Traditions, Modern Expressions at the Rutgers Gallery of the University of New Jersey, are repositioning Chinese art within Modernity. It is necessary to recognize the lead taken by the Anglo-Saxon world in this field. On the one hand, these exhibitions confirm the existence of universal criteria and conventions established by the west for contemporary and modern art, on the other, they demonstrate the new vitality of the arts of China. Institutions like the British Museum, through the impetus of Anne Farrer, have acquired modern art works. Significant donations have also enriched the collections of museums. They include gifts by the art historian Michael Sullivan to the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford or those by the painter and collector C.C Wang and the art dealer Robert Ellsworth to the New York's Metropolitan, or that by film maker Yonfan Manshih to the Musée Guimet in Paris. Modern, contemporary and future art history, even if we only consider the law of numbers, will have to take Asia into account. Therefore, the west must integrate the individual experiences of Asian artists, who traditionally regard art as a link between solitudes that ignore one another. T'ang himself used to say: "It is up to the individual, whatever his origins, to open his own path towards the arts." Philippe Koutouzis |

© Philippe Koutouzis

Foreword

|| Colors of Ink || Main -

Paths of Ink || Introduction

Asianart.com

|| Exhibitions

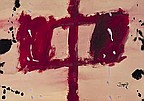

Large

calligraphy (104, left) evokes the Song of the Blue Sky a

calligraphy by Hsü Wei kept at the Shanghai Museum. Boldly, T'ang

links his own picture to characters whose clear, sharp and legible shapes

contrast with other abstract contours in cursive script. Unrestrained,

the pace and movement of his brush evoke life. On the left side of the

composition, one can read huí, the return, painted in

black ink, and zhong, the middle that symbolizes China, painted

red. The work also contains references to archaic forms, as hints or

reminders, but its originality lies in the depth created by the three

consecutive color planes: made up of red lines covered with blue and

black ink, in the foreground. The association of meaning and suggestion

within the same picture confirms a Taoist approach aiming to combine

different energies. It also exposes to our modern gaze the range of

expressive possibilities of an accomplished calligrapher. However, the

similarities between Asian and Western paintings, are merely formal.

What motivated Pollock was a deep personal anxiety, as opposed to the

expressive bliss of Chinese painters. Historically, the interactions

between East and West often merely resulted in borrowing a shape or

a process. The use of perspective is a prime example: it arrived in

Asia with European missionaries, then returned to Europe in the 19th

century, modified and adapted in the etchings of Hiroshige. Next it

influenced painters such as Van Gogh and his vision of the world, without,

however, tainting his work with the allusive value and the poetry of

the Hundred Views of Edo. T'ang simply applies this principle

when he uses Cézanne's Large Bathers as a way to produce

his own art. He observes the progress on both sides of the Atlantic

and can find in these currents a connection with Chinese classical tradition.

For instance in a treaty from the Song era where a row of trees is compared

to stretched arms with lengthened fingers. T'ang, however, does not

feel any metaphysical anxiety nor did he question the choice between

visual hypotheses of abstraction and certainties established by figurative

art. He continues to work in a detached way and positions himself between

the Far East - convinced of its own exception, absorbing and transforming

through the pace of a long history - and the West, revolutionizing through

the successive leaps of its schools and "new values".

Large

calligraphy (104, left) evokes the Song of the Blue Sky a

calligraphy by Hsü Wei kept at the Shanghai Museum. Boldly, T'ang

links his own picture to characters whose clear, sharp and legible shapes

contrast with other abstract contours in cursive script. Unrestrained,

the pace and movement of his brush evoke life. On the left side of the

composition, one can read huí, the return, painted in

black ink, and zhong, the middle that symbolizes China, painted

red. The work also contains references to archaic forms, as hints or

reminders, but its originality lies in the depth created by the three

consecutive color planes: made up of red lines covered with blue and

black ink, in the foreground. The association of meaning and suggestion

within the same picture confirms a Taoist approach aiming to combine

different energies. It also exposes to our modern gaze the range of

expressive possibilities of an accomplished calligrapher. However, the

similarities between Asian and Western paintings, are merely formal.

What motivated Pollock was a deep personal anxiety, as opposed to the

expressive bliss of Chinese painters. Historically, the interactions

between East and West often merely resulted in borrowing a shape or

a process. The use of perspective is a prime example: it arrived in

Asia with European missionaries, then returned to Europe in the 19th

century, modified and adapted in the etchings of Hiroshige. Next it

influenced painters such as Van Gogh and his vision of the world, without,

however, tainting his work with the allusive value and the poetry of

the Hundred Views of Edo. T'ang simply applies this principle

when he uses Cézanne's Large Bathers as a way to produce

his own art. He observes the progress on both sides of the Atlantic

and can find in these currents a connection with Chinese classical tradition.

For instance in a treaty from the Song era where a row of trees is compared

to stretched arms with lengthened fingers. T'ang, however, does not

feel any metaphysical anxiety nor did he question the choice between

visual hypotheses of abstraction and certainties established by figurative

art. He continues to work in a detached way and positions himself between

the Far East - convinced of its own exception, absorbing and transforming

through the pace of a long history - and the West, revolutionizing through

the successive leaps of its schools and "new values".