by Verena Ziegler

(click on the small image for full screen image with captions)

“I think you are also of the opinion that

In order better to appreciate works of art,

It is not unnecessary to understand them;

And that the first thing one has got to do,

After having duly admired their beauty,

Is to identify the subjects they represent.”

Alfred Foucher[1Foucher 1921, (1919-1920): 50.]

The life of Buddha Śākyamuni in Indian and Tibetan art:

“The most important themes in Indian Buddhist narrative painting are the life (avadāna) and previous lives (jātaka) of Śākyamuni ”, as Klimburg-Salter has stated.[2Klimburg-Salter 1995: 679-680.] The pictorial narrative of Buddha's life developed in India in a context where the believers were familiar with Indian philosophical concepts and religious methods. As the present worldly existence is just one of numerous existences, the individual life is not of primary concern. More important for Indian Buddhists was the spiritual development of Buddha Śākyamuni towards his Enlightenment. Due to the importance of pilgrimage in India the episodes from his life were coupled with the geographic place where they occurred. Thus the four major events of the historical life of Buddha Śākyamuni, his birth, the enlightenment, the first sermon and his death were grouped, respectively to Kapilavastu, Bodhgayā, Varanasi and Kuśinagara. These four pivotal events were complemented by four additional “miracles” - the madhu gift of the monkey in Vaiśāli, the taming of the mad elephant Nālāgiri in Rājagŗha, the Great miracles in Śrāvastī, like the multiplication of the Buddha image, the sudden growth of a mango-tree out of a mango-seed or the appearance of flames out of Śākyamuni's shoulders and water out of his feet; and the sojourn from Trayastriṃśa Heaven in Sāmkāśya - to form a group of eight “major events”.[3Eichenbaum-Karetzky 1992, Introduction, II, The Life of the Buddha: 6-7.

It can be observed that the depictions of the Buddha´s life in the Western Himalayas are mainly based on these eight major events but were extended with several "new" episodes out of different biographies on the Buddha´s life. See: Klimburg-Salter 1988: 209; 1995: 680 and 1997: 35-36.] Within the development of the pictorial language and through the influence of other visual models and folk stories, an independent visual tradition developed which seems to have varied from region to region. Thus different narrative modes developed, some with chronological order, as seen in the Gandhāran reliefs, but this was not the common rule.[4Klimburg-Salter 1995: 680.]

During the 10th and the 11th centuries, probably within the second diffusion of Buddhism (phyi dar), the need for an independent Tibetan tradition on the life of the Buddha emerged. For lack of an entire canonical Indian life-story of the Buddha in the 11th century the Tibetans attempted to piece together a full biography out of multiple textual sources, each containing just a segment of his life. The earliest fully preserved example of this Tibetan composition is the summary of the Buddha life in the “History of Buddhism” (Chos ´byung) by Bu ston (1290-1364), for which he drew largely from the Mūlasarvāstivāda-Vinaya, the Lalitavistara and the Abhiniṣkramaṇasūtra.[5See for Bu ston´s summary of his sources the translation by Obermiller: Obermiller 1932: 7-10; Klimburg-Salter 1982: 166; Luczanits 1993: 25-26; Luczanits 1999: 38.] The Tibetan biographies on the Life of the Buddha are termed “The Twelve Acts of the Buddha” (meaning “events” mdzad pa bcu gnis), with each act consisting of several scenes. In Bu ston´s account, one reads that these twelve acts of the Buddha tell his whole life-story, from his sojourn in the Tuṣita Heaven towards his parinirvāṇa.[6Klimburg-Salter is using the term “act” as the acts of a drama, “since every act consists of several scenes...” See: Klimburg-Salter 1988: 196, 208-209; Luczanits 1993: 25.] In contrast to the older Indian tradition, where the groups consist of four or eight acts, in which the dramatic climax of each act was presented, the Tibetan pictorial-narrative tradition seems to have been more fluid and detailed in its narration. This tradition in western Tibetan art starts the narration with the sojourn in the Tuṣita Heaven and so corresponds to the “Twelve acts of the Buddha”.[7Klimburg-Salter 1988: 209.]

Following the demise of the Tibetan monarchy in Central Tibet in the 9th century (842 CE) and within the context of the second diffusion of Buddhism (10th-12th centuries), Buddhism, Buddhist institutions and with them the literary and artistic Buddhist culture flourished in the far western Trans-Himalaya region in the kingdoms of Purang-Guge.[8Klimburg-Salter 1982: 152; Snellgrove 1982: 76.] In contrast to India, where Śākyamuni's life-story was integrated into the cultural landscape, the Indo-Tibetan borderlands had to address a heterogeneous audience, some of which, moreover, had to be converted. Using different well-known Indian textual sources to gain a complete life-story of the Buddha and integrating their own cultural and local traditions, the donors and the artists in Western Tibet created a self-sufficient linear and chronological way of representation for the life of the Buddha, fitted to the needs of a new Buddhist community in the Indian Himalaya. It can be observed that the narrative paintings of the Buddha's life in the Western Himalayas are mainly based on the traditional depiction of the eight major events but were extended with several “new” episodes out of different biographies on the Buddha's life.[9An example for the oldest preserved extended life-story of the historical Buddha in the Tibetan cultural area, can be found in the monastery of Tabo in Spiti, Himachal Pradesh. The wall paintings with the narrative scenes belong to the oldest preserved cycle on the life of the historical Buddha in the Tibetan cultural area, executed under the kings of Guge and dated around 1042 CE. For a detailed study of the Buddha life in Tabo and the development of the regional distinctions in narrative arts, see: Klimburg-Salter 1988: 209; 1995: 680, 689; and 1997: 35-36.]

The life of Buddha Śākyamuni in the skor lam Yum chen mo of Zha lu

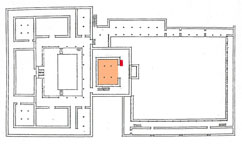

Fig. 1The monastery of Zha lu, in Central Tibet contains an extraordinary depiction of a whole Buddha-life in the circumambulation path (Tib. skor lam) of the Prajñāpāramitā (Tib. Yum chen mo) chapel. The outstanding aspect of these paintings is the kind of depiction, a conception that reminds of early Tibetan thangkas.

Fig. 2The monastery (Fig. 1), around 25 km south of Shigatse, in Central Tibet, was built by Chetsun Sherab Jungne (Lce btsun Shes rab ’byung gnas) in the 11th century C.E.[10Denwood 1997: 220; Vitali 1990: 89, 91-92.] One of the chapels of the monastery is dedicated to Yum chen mo. The chapel is located in the first upper storey of the monastery, on the eastern side of the complex, and its entrance-door opens onto the eastern wing of the surrounding corridor (Fig. 2).[11For more details on the structure of the Yum chen mo chapel see: Denwood 1997: 222.] According to Vitali, Chetsun Sherab Jungne probably built the Yum chen mo chapel shortly after erecting the first chapels of the monastery, the so-called twin chapels.[12Vitali 1990: 93.] The Yum chen mo chapel is surrounded by a skor lam, a circumambulation corridor, richly adorned with murals on the outer and the inner walls.

The purpose of this article is to examine a proportionally small part of these rich and unique paintings from the early 14th century within the skor lam Yum chen mo of Zha lu monastery. Outside of the chapel, on the internal wall to the South, left of the entrance door, there is a mural depicting the life story of Buddha Śākyamuni (Fig. 3-4), beginning with his final preaching in Tuṣita heaven and ending with the cremation of his body (Fig. 4a). Here I will just try to highlight the iconography and elements of their Newari- and Chinese stylistic influences.[13I hope to return to a fuller study of the stylistic aspects of this chapel in the future.] Today the paintings are in quite poor condition, and thus the content of some of the episodes must unfortunately remain to be determined.

Fig. 3 |

Fig. 4 |

Fig. 4a |

Between 1306 and 1320 Dragpa Gyeltsen (Grags pa rgyal mtshan), a nephew of Sakya Pandita (Sa skya Paṇḍita), who was the head of the Sakya lineage at this time, enlarged and renovated the monastery of Zha lu.[14Denwood 1997: 227; Vitali 1990: 99-100.] According to Vitali, he went to the Mongol court in the year 1306 and returned from there in 1307 with an entourage of artists, who were said to have been trained by the famous Nepalese artist Aniko, or Anige (1244-1306) at the Yuan court.[15Vitali 1990: 103-105. Vitali had emphasized that the famous Aniko himself could not have been part of the workshop that embellished the skor lam Yum chen mo and executed the paintings, since he had already died in 1306.] From the beginning of the 13th century, the artistic culture of the Kathmandu valley and the artistic culture of the Mongol Yuan court were favored by the monastic order of the Sakya in Tibet, of which Zha lu was a branch monastery situated along one of the major ancient trade routes leading to the Kathmandu valley.[16Tucci 1949, Vol.1: 277; Heller 2002: 47.] There are different opinions concerning the beginnings of the Nepalese influences in the decorations of the early monasteries of Central Tibet. According to Kossak, the murals of Zha lu from the early 11th century were Indian in style, while the paintings of the later period show a strong Nepalese influence. He states that this was probably due to the destruction of the great North-Indian monasteries and their ateliers by the Turkish invaders in 1192 and that from this time on the pan-Indian style of the Nepalese artists was a new sophisticated variant for the Tibetan patrons.[17Kossak 1998: 41.]

In contrast, Heller presented in her 2002 article about a Tibetan block print text about Atiśa's visit in Zha lu monastery, from the mid-16th century, that the title of the block print already recounts the genealogy of Lce btsun Shes rab ’byung gnas, the founder of Zha lu monastery, and tells about the foreign origin of the donors during the foundation, as well as the “importance of Nepalese aesthetic influences during the 11th century.”[18Heller 2002a: 46; The block-print text is entitled: Chos grva chen po dpal zha lu gser khang gi bdag po jo bo lce’i gdung rabs ; For more detailed information on this text and the Nepalese aesthetic influences on the art of Zha lu monastery during the 11th century See: Heller 2002a: 45-58 plus plates and Heller 2002b: 39-72.] If there were Nepalese donors there might have been Newar artists as well, and in any case it is documented that Atiśa resided in Kathmandu during 1040 and 1041, before he left for western Tibet in 1042 and central Tibet in 1045, possibly accompanied by Nepalese artists, as Heller has emphasized.[19Heller 2002a: 47-48.]

In 2010 Jackson returned to the destruction of the key monasteries and their arts in Pāla Sena India, who predominated in Tibet since 1300, as he states, by the Turkish invaders in 1203; and Nepal as a remaining living source of Indic Buddhist art for the Tibetans.[20Jackson 2010: Preface xi. In contrast to Kossak 1998: 41, Jackson sets the destruction of the monasteries in Indian Bihar and Bengal by the Turkish invaders on the year 1203. See: Jackson 2010: Preface xi.]

The composition of the life of the Buddha on the outer wall of the Yum chen mo chapel is shown in a rectangular manner (Fig. 4a). An over life-sized Buddha Śākyamuni can be seen in the center, sitting in meditation with the gesture of bhūmisparśa. He is sitting on a lotus-throne, obviously while gaining enlightenment, with a multi-lobed crown on his head, and is shown more in the manner of a Bodhisattva than a Buddha. To the left and the right of the seated Buddha, beside both knees, the head of a white elephant is depicted. He is flanked by two standing Bodhisattvas. The assumption that these figures represent the Bodhisattvas Avalokiteśvara, to the Buddha's proper right side, and Maitreya to his left side is difficult to determine because their original body-color might have changed over the centuries and none of their typical attributes can be detected, which may be attributed to the generally poor state of preservation.[21If Avalokiteśvara is shown here he should be white-skinned, holding a padma and Maitreya should have a gold colour, presenting the nāgakesvara or the kamaṇdalu , as Bautze-Picron has already pointed out. See: Bautze-Picron 1995/96: 357.]

Fig. 5 |

Fig. 6 |

Fig. 7 |

Opposite this section, on the outer wall of the skor lam, a Buddha Śākyamuni in bhūmisparśa mudrā is depicted facing the image on the opposite wall. He is surrounded by numerous figures and narrative scenes. According to Vitali, these paintings are part of a depiction of the Ma ga dha bzang mo (Fig. 5-6).[22Vitali 1990: 106 and Pl. 65; A more detailed description of these paintings is the content of another paper.]

Fig. 8 |

Fig. 9 |

Fig. 10 |

Fig. 11 |

Fig. 12Returning to the other side of the skor lam and the life of the historical Buddha, one can see that around the head of Buddha Śākyamuni, in a half-round shape, five depictions are grouped, all showing a Buddha sitting in the center of an arc. The Buddha above his head with a white body-color and shown in dharmacakra mudrā corresponds to the iconography of an aspect of Buddha Vairocana, the one above his left shoulder Buddha Amitabha in dhyana mudrā and below him Buddha Amogasiddhi in abhaya mudrā. The one above Śākyamuni´s right shoulder is Buddha Akshobhya in bhūmisparśa mudrā and below him Buddha Ratnasambhava in varada mudrā.[23Bautze-Picron has already pointed out the presence of the five Jinas above the head of the Buddha in bhūmisparśa mudrā at the center of a thangka with 27 episodes out of Śākyamuni life around it from the private collection of Heidi and Ulrich von Schröder, dated to around the 13th century. See: Bautze-Picron 1995/96: 359-360, 381.] Mārā's troops, composed of demons and wild animals, surround the whole central depiction. Within an almost closed rectangular shape, 28 episodes of the life of Buddha Śākyamuni are shown, beginning at the top right moving clockwise, each framed by a thin rectangular frame, some with a Tibetan inscription on the lower border (Fig. 7). The narration starts on the uppermost right corner, with a scene showing the Buddha-to-be at his last preaching in Tuṣita heaven, flanked by two deities and holding a white conch in his hands (1, Fig. 8), and continues vertically downwards. In the next episode the Bodhisattva, still in Tuṣita heaven, is shown together with Maitreya, the Buddha of the future, who has a darker body-color and kneels in front of him, (2, Fig. 9). Below that the Bodhisattva is shown again, this time in the form of a large white elephant standing on top of a roof. Inside the house queen Māyā sleeps on her right side while a small white elephant is shown above her in the episode of the conception (3, Fig. 10).[24Biographies like the Lalitavistara and the Nidānakathā stress that the Bodhisattva, as a white elephant, entered his mother´s right side, referring to the narrative tradition that he emerged from the same side during his birth. But other texts as the Mahāvastu tell that the queen was lying on her right side, because lying on her left would have been a sign for sensuality. Because of this “dilemma” the artists showed her in both ways, lying on her right and on her left side, as Schlingloff has pointed out: See: Schlingloff 2000: 311.] The narration continues with Śākyamuni's birth, the first bath and the first steps, all in one frame (4, Fig. 11). In this depiction Māyā is shown to the viewer´s right, giving birth to the Bodhisattva while grabbing a branch of the tree above her with her right arm.[25All the textual sources on the life of Buddha Śākyamuni, except for the Buddhacarita which tells that she was lying on a bed, correspond that Māyā was standing upright while giving birth to the Bodhisattva. See: F. Weller, 1926, transl.: 4; E.H.Johnston, 1936/1972: 3; Schotsman, 1995: 3.] In front of her, to her proper right, the god Brahmā is depicted awaiting the newborn child, with precious cloth in his hands.[26Different biographies on the life of the historical Buddha, such as the Mūlasarvāstivāda-Vinaya , the Lalitavistara and the Buddhacarita tell of the presence of the gods Indra (or Śakra as he is named in the Lalitavistara ) and Brahmā during the birth of the Bodhisattva. See: J.L. Panglung, 1981: 85; R.L. Mitra, 1998: 114.

In the arts of the Kuṣāṇa it has always been Indra receiving the newborn child. See: Williams 1975: 176.] Above them a deity in a cloud can be seen, maybe giving the first bath to the Bodhisattva.[27According to the Nidānakathā , the Mūlasarvāstivāda-Vinaya , the Mahāvastu and the Buddhacarita the waters bathing the Bodhisattva come out of the airspace and only the Lalitavistara tells of two nāgas , the brothers Nanda and Upananda (or Kāla und Akāla) bathing the Bodhisattva. See: Schlingloff 2000: 332; Williams 1975: 176.] On the left side the first seven steps of the newborn child are depicted in a quite extraordinary way. The artist has obviously put the seven Lotus flowers, emerging from the first steps of the newborn Bodhisattva, above each other, and so built a kind of hill with the standing Bodhisattva on its top with his left arm raised. The first bath and the first steps are often shown side by side within a single depiction as Schlingloff has noticed. According to the Mūlasarvāstivāda-Vinaya-tradition the first steps happened before the first bath, while the Lalitavistara reverses the events.[28Schlingloff 2000: 328.] The next episode below shows in a quite common manner the prediction by the sage Asita, who detected the numerous lakśanas of an auspicious being on the newborn child. On the right side Asita is shown, in a dark grey color, dressed like a typical Indian rishi, with his arms stretched out to receive the Bodhisattva.[29In some biographies, like the Buddhacarita or the Nidānakathā the Bodhisattva is just shown to Asita, but other texts, like the Mūlasarvāstivāda-Vinaya , the Mahāvastu and the Lalitavistara tell that the young prince was set on the rishi's lap. The image of the Bodhisattva sitting on Asita's lap was quite common in Gandhāran art, but the present author has not yet seen a depiction in Tibetan art that shows the episode in this way. See: Schlingloff 2000: 343; Rhys Davids 1880/2000: 69; Mitra 1998: 128; Goswami 2001: 101; Jones 1952: 35.] The male figure sitting behind him probably depicts his nephew Naradatta or Nālaka who, according to many of the biographies such as the Mūlasarvāstivāda-Vinaya or the Lalitavistara, accompanied his uncle at the palace. (5, Fig. 12).[30Schlingloff 2000: 343; Mitra 1998: 127; Panglung 1981: 85.] On the left of the frame the royal couple can be seen with the king holding the Bodhisattva on his lap and the queen behind him.[31In the arts of India, such as the Gandhāran depictions of this episode, the queen is not shown in this episode, but in most of the Tibetan examples known to the author the queen is present, sitting behind the king and the child.] In the scene below the Bodhisattva is shown at school while learning to write with the teacher sitting at the left of the frame and the Bodhisattva and a second pupil to the right side. All three hold a book in their hands. Behind them a tree denotes that the class takes place outside (6, Fig.13).[32In the reliefs of Gandhāran art the episode of the Bodhisattva at school always takes place in nature, in contrast to the paintings in Ajaṇṭā where it is depicted inside a room. See: Schlingloff 2000: 346.] The narration continues with different kinds of tournaments that the young prince attended according to his biographies, such as throwing the dead elephant that had been killed by his cousin Devadatta, the archery contest where he had to shoot straight through several palm trees, drums and boar sculptures (7a, Fig. 14), and a wrestling and a swimming contest (7b, Fig. 15).[33Schlingloff 2000: 349. The numbers of palm trees, drums and boar sculptures differ from text to text.

The reasons for these tournaments vary from text to text. Some tell that the young prince was challenged by other young men, others say he had to show his strength to receive his bride (Mahāvastu) or that the king just wanted to cheer up his son. In this case, if we have a look at the following depiction below, the tournaments might be in connection with the bride Yaśodharā. See: Schlingloff 2000: 349; Eichenbaum-Karetzky 1992: 42.] Below these two chapters the Bodhisattva is shown sitting on the left, perhaps inside of the palace of his father, and choosing Yaśodharā as his bride out of several young women (8, Fig. 16).[34The episode of choosing his bride Yaśodharā is told in a quite similar way in all biographies; the Bodhisattva gives jewelry to all the women and a special ring to Yaśodharā. In Gandhāran art this episode is always narrated with the content of the marriage, showing the Bodhisattva and his bride walking around the fire. See: Schlingloff 2000: 350.] In the lower right corner, a palace in Chinese style containing sleeping figures is shown, which may anticipate the episode of the renunciation of the Bodhisattva that follows the sequence of the four encounters (9a, Fig. 17).

Fig. 13 |

Fig. 14 |

Fig. 15 |

Fig. 16 |

Fig. 17 |

Fig. 18 |

Fig. 19 |

Fig. 20From this point the narration continues horizontally to the left with the four encounters or four meetings, divided into two frames. In the first frame, connected with the palace, the Bodhisattva is shown sitting on a cart with a big umbrella above him (9a).[35Although the biographies tell that the Bodhisattva experienced the four encounters together with a servant while sitting on a cart drawn by horses, most of the reliefs from Gandhāra show him riding a horse. See: Schlingloff 2000: 353.] In the second part five figures are depicted. On the right side the Bodhisattva can be seen standing under a tree and in front of him a male figure, dressed in black with a stick, probably the old man, and the figure behind him looks like a monk. In front of them a figure lies on the ground, probably the dead man, but without anybody else carrying him on a stretcher, as told in the textual sources. The last figure on the left is badly preserved and must be the sick man, maybe holding his swollen belly (9b, Fig. 18).[36In the arts of Gandhāra and Mathura the sick man is normally depicted sitting on the ground holding his swollen belly. See: Schlingloff 2000: 354.] In the next frame we can see the renunciation or the Great departure that shows the Bodhisattva on his horse Kaṇṭhaka being carried out of the palace by four gods who lift the horse to prevent any noise (10, Fig. 19). This is followed by the tonsure, almost in the center of this lower frame, with the Bodhisattva holding a sword with his right arm, flanked by the gods Brahmā to his proper right side and Indra to his left, ready to receive his hair. On the very right of the scene a white mChod rten is depicted (11, Fig. 20).[37Bautze-Picron has already pointed out the “central” position of the tonsure and the importance of this episode in Śākyamunis biography and correspondingly that the Bodhisattva from this scene on is depicted as a Buddha in all following episodes, although he had not yet reached enlightenment. See: Bautze-Picron 1995/96: 369, 371.

The Lalitavistara tells us that, after the Bodhisattva had cut his long hair with his sword, he threw it up to the sky. The Trayastriṃśa gods took it to worship and a caitya was built that is known as Cuda-pratigrahana. See: Goswami 2001: 212.] This episode is probably followed by the depiction of switching his princely clothes with the hunter (12, Fig. 21).[38According to the Lalitavistara, a devaputra, concealing his divine form, stood before the Bodhisattva in the form of a hunter covered with a red cloth, “And he (the devaputra) took the fine cloth of the prince and went with them to heaven to worship them. There too a caitya was built, that is known as Kasayagrahana ...” See: Goswami 2001: 212.] In the next episode the Bodhisattva, already depicted as a Buddha, as in all the episodes after the tonsure, is shown seated on the right side of the scene with a female figure in front of him, offering him something that looks like a bowl. Left behind her, another figure can be seen sitting inside of the entrance of a house, which probably represents a village (13, Fig. 22). If the scene of Sujātā offering the milk-rice to the Buddha is located here it would be placed in the wrong order [39In the episode of the milk-rice some biographies, such as the Mahāvastu, the Lalitavistara and the Nidānakathā, tell of the milk-maid Sujātā; in the Buddhacarita she is named Nandabalā, and the Mūlasarvāstivāda-Vinaya tells of two sisters named Nandā and Nandabalā. See: Schlingloff 2000: 371.], because of the following episode to the left, which shows two villagers irritating the fasting Bodhisattva by prodding his ears with sticks or dust, thinking that he is dead (14, Fig. 23).[40“And the village boys and girls, the cowherds, shepherds, and those who gathered grass, food, and dung, all took him for a dust demon and made fun of him, throwing dust over him“ as Foucher points out. See: Foucher 1963: 101.

According to Schlingloff, this story about the pestering by the village-boys comes from the Majjhimanikaya , and thus belongs to the oldest Buddhist literary tradition. In this report the Buddha tells of cowherds who threw dirt and dust on him while he was meditating and who prod wooden stick into his ears. See: Schlingloff 2000: 369.

“...Da machte ich mir auf einem Totenacker aus Leichenknochen ein Lager. Da kamen Rinderhirten, spuckten und harnten und bewarfen mich mit Kotklumpen und steckten mir Grashalme in die Ohren...” See: Schmidt (tr.) 1989. “Buddhas Reden. Majjhimanikaya ”: 49.

The Lalitavistara just tells about village-boys and girls, cowherds etc. who thought the Bodhisattva is a dust-goblin and threw dust and mud on him. See: Goswami 2001: 240, 242.] In the next episode a group of people is shown on the left with the standing Bodhisattva on the right border. Again a figure is standing in front of him, offering something to him (15, Fig. 24). This image perhaps shows the episode with the milkmaid Sujātā giving the first meal to the Buddha-to-be after his austerities. Another possibility is that this episode depicts the Buddha´s first meal after his enlightenment, given to him by two merchants, the brothers Trapuśa and Bhallika, who had passed by with a caravan of some one hundred ox-carts.[41For the detailed story see Foucher 1963: 131.] The last scene on the leftmost corner is so poorly preserved that its content is no longer identifiable (16, Fig. 25).

Fig. 21 |

Fig. 22 |

Fig. 23 |

Fig. 24 |

Fig. 25 |

Fig. 26 |

Fig. 27 |

Fig. 28 |

Fig. 29 |

Fig. 30

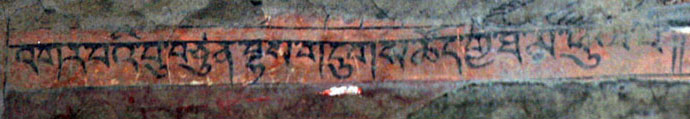

Fig. 31From this point the narration is organized in a vertical manner again, but this time proceeding from the bottom to the top along the left side. The next episode is quite badly preserved too, but the seated Buddha protected by Mucilinda and accompanied by other nāgas can still be seen (18, Fig. 26).[42After his enlightenment the Buddha stayed in meditation for another seven days without uncrossing his legs. See: Goswami 2001: 319. Foucher points out: “As it is the rule for kings not to leave for seven days the place of their coronation, so it is for Buddhas when they have been consecrated to remain in contemplation for seven days, without uncrossing their legs.” See: Foucher 1963: 128.] Because this episode is said to have happened after the enlightenment, while the Buddha remained in meditation for seven more days or seven more weeks, the eye of the beholder must first turn to the central depiction of the enlightenment, with Buddha Śākyamuni seated on a lotus-throne (17), before continuing with the narration vertically on the left.[43The length of the Buddha´s meditation after his enlightenment and before he took his first meal differs in the various texts. The Lalitavistara records seven more weeks: “During the fifth week he was protected by Mucilinda and other nāgas , because of the foul weather”. See: Goswami 2001: 346; Rockhill 1907/2000: 34-35.] The next scene above the Mucilinda episode shows the grass-cutter Svastika´s offering of the Kusha grass to the Bodhisattva depicted as a conflated narrative as termed by Dehejia, first showing Svastika cutting the grass and then offering it to the Buddha-to-be (19, Fig. 27).[44Conflated narrative means, according to Dehejia, that the figure of the protagonist Buddha is conflated, instead of being repeated from one scene to the next. See: Dehejia 1997: 25.] According to the biographies on the Buddha´s life, this episode took place before his enlightenment, when Svastika gave him the Kusha grass to sit on under the Bodhi tree, and in this case this scene should have been shown before the depiction with Mucilinda.[45The Lalitavistara relays the episode of the Bodhisattva and the grass-cutter Svastika, who had quite an extensive exchange of words before the Bodhisattva received the Kusha-grass to sit on under the Bodhi Tree. See: Goswami 2001: 266-268.] Above this episode the offering of the begging bowl by the four Great Kings of the cardinal points is shown, where the Buddha received four begging bowls, one from each king, and made them into one bowl (20, Fig. 28).[46Foucher 1963: 131-132.] The Buddha is seated on a lotus with a long stalk, in front of which a figure kneels. Śākyamuni is holding a single begging bowl in his hands. The four Great kings are shown around him, each holding a begging bowl.[47The Lalitavistara tells that he transformed these four bowls into one just by his will, but the Mahāvastu tells that he caused the bowls to fit into one another with pressure from his thumb. See: Foucher 1963: p.132; Goswami 2001: 350.] The next scene might show the first sermon of the Buddha in front of the five ascetics, although six figures are shown around the central Buddha (21, Fig. 29). It is difficult to identify the depiction clearly because the mudrā of the Buddha is lost, but it looks as if it might have been the dharmacakrapravartana mudrā. Buddha Śākyamuni sits on a high throne surrounded by these six figures. The three figures to his left are depicted like Indian sadhus with a big hair-knot, and two of the three figures to his right are dressed like Buddhist monks. The third figure on the right, which looks slightly painted over, seems to offer something to the Buddha with the Tibetan letter ![]() on his chest. Taming the mad elephant Nālāgiri in Rājagṛha can be seen in the next episode (22, Fig. 30), depicted in a circular conflated narration. Reading clockwise from right to left: the smaller figure of Devadatta, causing the situation and pointing at it with his right arm; the mad elephant in dark grey; the Buddha on the left with a monk in front of him; and finally the tamed elephant in light brown, behind the mad grey one, bowing his head in front of the Buddha. This episode is followed by a preaching scene, which, according to the inscription on the frame below, shows the dispute of the Buddha with the six Tīrthika masters in Śrāvastī (23, Fig. 31-31a).[48mus rtegs (read: mu stegs ) ston pa drug-ul (( b )rtul or (’)dul ?). The gathering (or taming/subduing?) of the six Tīrthika teachers.

on his chest. Taming the mad elephant Nālāgiri in Rājagṛha can be seen in the next episode (22, Fig. 30), depicted in a circular conflated narration. Reading clockwise from right to left: the smaller figure of Devadatta, causing the situation and pointing at it with his right arm; the mad elephant in dark grey; the Buddha on the left with a monk in front of him; and finally the tamed elephant in light brown, behind the mad grey one, bowing his head in front of the Buddha. This episode is followed by a preaching scene, which, according to the inscription on the frame below, shows the dispute of the Buddha with the six Tīrthika masters in Śrāvastī (23, Fig. 31-31a).[48mus rtegs (read: mu stegs ) ston pa drug-ul (( b )rtul or (’)dul ?). The gathering (or taming/subduing?) of the six Tīrthika teachers.

According to the Mahāparinirvāṇa sūtra the Buddha went to Śrāvastī together with six Indian teachers, the so called Tīrthika masters. See: Page 2007: 411. The Tīrthika, the deluded or heterodox believers, the non-Buddhists, are mentioned quite often in the sūtra in different chapters. In chapter “Fourty-Five: On Kaundinya ” the Buddha is asked by king Ajatasatru to answer the questions of several Tīrthika masters who finally all convert to Buddhism. See: Page 2007: 551-580.

According to Eimer, one can find the description of the six philosophies of life all contrary to the dharma of the Buddha in the canon of several Hīnayāna schools of Buddhism. The most detailed versions can be found in the Vinaya of the Mūlasarvāstivādins. In this corpus on order’s discipline, which was translated into Tibetan and integrated into the Kanjur , the Tīrthika episode is part of the Vinayavastu and appears there in two parts: One in the Pravrajyāvastu (Tib. Rab tu `byung ba`I gzhi ) and one in the Saṅghabhedavastu (Tib. Dge `dun gyi dbyen gyi gzhi ). Between 1351 and 1354 Bu ston Rin chen grub provided a collection of narrations out of the Vinaya with the title `Dul ba pha`I gleng `bum chen mo that also contains a short version of the episode about the six Tīrthika masters as a part of the description of the youth of Śāriputra and Maudgalyāyana. In this text the six masters are mentioned by names: Purana Kasyapa, Maskarin Gosaliputra, Samjayin Vairatiputra, Ajita Kesakambalin, Kakuda Katyayana and Nirgrantha Jnatiputra. See: Eimer 2007: 43; 47-52.] As it is written that the “Śrāvastī-miracle” occurred because six itinerant preachers, who had brought disaster on their followers through false teachings, challenged the Buddha to a demonstration of his spiritual ability, we might assume that this depiction shows the “Great Śrāvastī miracle” in a more uncommon way, and that the tree behind the Buddha might be the mango tree he had grow out of a seed of a mango.[49Schlingloff 2000: 488, 498.] Above, the madhu gift of the monkey is shown again in conflated narration: the monkey offers the honey-bowl to the Buddha sitting to the left; the happily dancing monkey; and the death of the monkey, who throws himself in a well to be reborn as a heavenly creature (24, Fig. 32).[50Deheija 1997: 15-16; Schlingloff 1981: 88-89, 95.] The next episode is very poorly preserved. The sitting Buddha on the left and two standing figures to the right in front of his lotus throne can be made out (25, Fig. 33). According to the inscription below it (Fig. 33a), the depiction shows the Buddha at the house of Chunda the son of the blacksmith, who was probably also a blacksmith, in the village Pāvā.[51bgar (Read: mgar ) ba’i bu bcun bhas (Read: cun das ) gdugs tshod gyi zas phul ba //. The offering of lunch by Cunda, the son of the blacksmith.; See: Foucher 1963, p. 230.] Chunda offers the last meal to the Buddha before Śākyamuni's parinirvāṇa.[52According to Eichenbaum-Karetzky some texts tell us of tainted meat; whether it was pig meat, or the food eaten by pigs, namely truffles, has long been debated. See: Eichenbaum-Karetzky 1992: 192.] The second figure on the right could be the smith´s wife. The last scene on the uppermost section to the left is part of a horizontal depiction, showing the mahāparinirvā ṇ a of the Buddha (26, Fig. 34). The Buddha can be seen lying with five monks sitting in front of the bed and five others standing behind it mourning him. The monk seated in front of the Buddha´s feet touches them with his hands and can therefore be identified as Mahākāśyapa. At both ends of the bed two figures wearing a crown and a halo are depicted; one has white body-color near his head and the other has darker body-color near his feet, thus they might represent the gods Indra and Brahmā. To the left of the scene four upright figures walking towards the bed can be seen (Fig. 35). The leftmost is dressed with Chinese cloth, the second is dressed like a monk holding a begging bowl in his hands and the third, again dressed like a monk, is holding a stick. The fourth, also dressed like a monk, is bareheaded. The first three appear to wear an uṣṇīṣa and a halo. To the right a single monk is seated behind the crowned god beside the Buddha's feet. In a horizontal manner again but connected to the scene of the preaching in Tuṣita on the right side, the cremation of the body of the late Buddha is shown as the last episode of the cycle (27, Fig. 36). Because of its poor preservation the depiction is not easy to be read. A large fire on a platform is located in the centre with two seated monks to its right and a crowned figure seated on a lotus with four upright figures behind it to the left.[53Maybe this sitting divine figure depicts Vajrasattva, holding the vajra in front of his breast and the ghanta with his left hand, “...who appears in the upper register in the later paintings...”, as pointed out by Bautze-Picron. See: Bautze-Picron 1995/96, p. 367-368.] Three of them are dressed as monks and the last one wears a Chinese coat with long sleeves. Two small figures dressed in blue sit in front of the platform. To the left and the right of the fire, near to the top, two small deities are depicted inside of clouds.

Fig. 31a |

Fig. 32 |

Fig. 33 |

These murals in Zha lu confront us with the whole life story of the historical Buddha in a very elaborate manner, most likely based on the Lalitavistara, which was most prevalent at that time, but also incorporating other texts like the Mūlasarvāstivāda-Vinaya, the mahāparinirvāṇa sūtra and others.[54Because the narration of the Lalitavistara ends with the first sermon of the Buddha, other textual sources on the Buddha´s life must have been drawn upon to depict the whole life story ending with the cremation of the late Buddha. See: Klimburg-Salter 1995: 680.]

Fig. 33a |

Fig. 34 |

Fig. 35 |

Fig. 36 |

The life of Buddha Śākyamuni on Tibetan thangkas

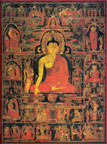

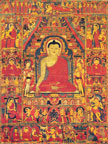

When one compares the Zha lu murals with roughly contemporary Tibetan thangkas showing the life of Buddha Śākyamuni, - such as one from the Zimmermann collection, around 12th century C.E. (Fig. 37), one from a private collection, probably late 13th to early 14th century C.E. (Fig. 38) and one from the collection of Heidi and Ulrich von Schröder (Fig. 39) - it becomes apparent that the paintings in Zha lu are conceived in a similar manner to the thangkas: a much larger Buddha sitting on an elaborate throne gains enlightenment in the center, with episodes from his life arranged around him in a rectangular manner.[55I shall not describe the thang kas in detail and will not go deeper into their influences from Pāla-art, Bihar, Bengal or Bagan, because this has already been undertaken in detail by Bautze-Picron and Allinger. See: Bautze-Picron 1995/96; Allinger 2010.] According to Bautze-Picron, the first two thangkas mentioned display a symmetrical order, which cannot be detected in the murals.[56According to Bautze-Picron specific scenes are always paired, such as the taming of Nālāgiri with the descent at Sāṃkāśya, the first predication at Sārnāth with the Śrāvastī Miracle and the gift of madhu at Vaiśāli with the birth in Lumbinī, which is definitely not the case in these paintings. See: Bautze-Picron 1995/96: p. 363.] While in the thangka of the Zimmermann collection and in the thangka of the private collection six main events are depicted larger in size in two vertical registers, and just a few more smaller scenes on the lower and the upper registers, the thangka from the von Schröder collection “illustrates a further step in the development” as Bautze-Picron pointed out in her 1995/96 article.[57Bautze-Picron 1995/96: 356.] Here 27 square panels contain depictions from Śākyamuni's life on the side and the lower registers, and the parinirvāṇa and the cremation are shown in the upper register.[58Bautze-Picron 1995/96: 356.] The head of the central Buddha in the thangka is surrounded by the five Jinas sitting inside of arcs as in the Zha lu murals, but the Buddha does not wear a crown and is flanked by two monks instead of Bodhisattvas as in the paintings of Zha lu. With the exception of the missing arhat depictions, the main composition of the thangka is quite similar to that of the murals. Although in both artistic media the episodes are depicted in the restricted space of closed rectangular frames, the scenes in the murals seem much more lively and animated. This impression may well be more a question of space for the artist, as the murals offer more surface than the much smaller thangka.

Fig. 37 |

Fig. 38 |

Fig. 39 |

Fig. 40 |

As in the murals, the von Schroeder thangka starts with Śākyamuni in the Tuṣita heaven and ends with the cremation of his body. In the thangka the episodes in Tuṣita heaven fill three frames and continue with the birth, without showing the conception. The episode of choosing his bride is shown before the various contests, and the changing of clothes with the hunter before the tonsure. The scenes with Sujātā and Mucilinda are in the correct chronological order, but the depiction of the grass-cutter Svastika is missing. The episodes with the merchants Bhallika and Trapuśha, the first sermon and the four Kings of the directions are in the correct order again, according to the literary sources, followed by the miracle of Śrāvastī and the dispute with the six Tīrthika masters, here shown in two separate frames. The narration continues with the gift of madhu, the taming of Nālāgiri and the Buddha's descent from Trayastriṃśa Heaven to Sāṃkāśya, a depiction which is completely missing in the murals. The last episode in the upper left corner obviously shows a preaching scene with the Buddha in dharmacakra mudrā in the center with four crowned figures surrounding him. The upper register is arranged in a similar manner with the parinirvāṇa and the cremation, but in contrast to the murals, where the center of the register is occupied by the elliptically shaped Bodhi tree surrounded by flames, the thangka shows the parinirvāṇa in the center. In the episode of the cremation on the thangka, the head of the Buddha can be detected in the center of the flames, but it is missing in the murals.

Nepalese and Chinese influence

In the murals in Zha lu the Nepalese influence can be clearly detected in the firm but fluid drawing, the rich and warm coloration (to the extent that one can today speak of original coloration) and the animation of the figures, their liveliness, their somewhat rounded faces, tubular limbs and the creation of volume by color modeling.[59See for a detailed comparison of Indian and Nepali characteristics: Losty 1989: 86; and Heller 2002a: 49.] One can also see the opulence of the Buddha's robe with its decorated edges, the decorative lotus petals, the floral patterns around his halo and the vegetal flames around the Bodhi tree above the Buddha's head.[60For more detailed information on Newar-influence in the murals of Zha lu, See: Heller 2002a and 2002b; Vitali 1990: 106 - 109; Jackson 2010:105-107.]

According to Kossak and Vitali, the first major appearance of this Chinese influence can be seen in the Zha lu murals that were painted about 1306-07, and these Chinese elements had only sporadic influence on the art of 14th century Tibet.[61Kossak 1998: 45. “In the early fourteenth century, Shalu monastery was thoroughly renovated and transformed into a complex conceived in accordance with the fashion in vogue in China at the time.” See: Vitali 1990: 89.] In the murals there are only some minor elements like the depiction of the sleeping palace or other architectural details in the episode with Sujātā or the taming of Nālāgiri that might refer to Chinese influence. There are also some figures depicted in a kind of Chinese flowing robe, with wide sleeves, held at the waist with a belt, as Vitali and Kossak have already pointed out in detail, and the four Kings of the directions are depicted like Chinese military authorities in the murals.[62According to Vitali, Nepalese Newari influence is the cohesive element of these murals in Zha lu, while Yuan stylistic features are mainly used for minor details such as the Chinese influenced architecture, such as pavilions and temples and Chinese-looking men in Chinese costumes with black caps. See: Vitali 1990: 106.

Kossak has pointed out that from at least the 12th century the Guardians of the directions are shown wearing Chinese armor. See: Kossak 1998: 46.] According to Vitali, Aniko's atelier may, moreover, have been composed of a multinational group of Tibetan, Chinese and Nepalese painters.[63Vitali 1990: 106. Kossak pointed out that the most likely explanation for the style of the major images:"...a Nepalese variant with some Bengali and Central Asian elements...” is that they were painted by artists trained in Aniko´s probably multinational atelier. See: Kossak 1998: 43.] Some of the paintings of the internal walls of the skor lam of the Yum chen mo chapel bear inscriptions, and Vitali has already pointed out that some of these inscriptions name the artist as Chimpa Sonam Bu (Chims pa bSod names ’bum) whose clan appellative 'mChims pa' identifies him as Tibetan.[64From the appearance of the Tibetan name Vitali goes further to state that Aniko´s workshop consisted of multinational artists and that Chimpa Sonam Bu might have been a member of it: “The fact that the literary sources stress that artists were summoned from the Yuan court to Zha lu reinforces the evidence that Chimpa Sonam Bu might have been also a member of this Yuan court workshop”. See: Vitali 1990: 106, 108.] Vitali has also pointed out that based on the similarities in details and style in many of the murals of the interior walls of the skor lam Yum chen mo Chimpa Sonam Bu must have been the artist who painted the whole interior wall of the skor lam, even though many of the panels are unsigned.[65Vitali 1990: 108. This mentioned assignment seems to be a bit generalized to the present author but is not the content of this article and needs an extensive analyse and comparison of the style, the iconography and the time of origin of the murals of the entire skor lam around the Yum chen mo chapel.

Jackson states: “But the Tibetan sources never say or imply that all artists who worked at Shalu came from Yuan China. That would have been a matter of impossibility for a project of that size, complexity, and duration... It seems equally possible that the skills of Chimpa might have been requisitioned from somewhere in Tsang or Tibet, as one of the best available professional painters...” See: Jackson 2010: 107.]

On a photograph taken by Mahāpaṇḍita Rahula Sāṅkṛtyāyana during one of his journeys to Tibet in the 1920s and 1930s, a part of the murals can be seen, including some episodes of the vertical narration path on the right side (Fig. 40).[66Pathak 1986: Plate 8.] The frames with the episodes of Śākyamuni and Maitreya in Tuṣita, the conception, the birth, the visit of Asita, the Bodhisattva at school and the different tournaments can clearly be recognized. However the meeting with Yaśodharā and the Chinese palace below seem to have been in a quite poor condition at that time. This evidence raises the question of how much is really left from the original murals of the early 14th century and how much has been repainted and added in later times.

Conclusion

In closing we can observe that the murals in the skor lam of the Yum chen mo chapel in Zha lu were obviously influenced by earlier and contemporary thangka paintings, and quite probably vice versa, including unique influences from earlier Indian Pāla art, Nepalese Newar art and Chinese Yuan art.[67From around 1100 to 1300 the Pāla art predominated in Tibet. Because the key monasteries in India and Bengal, the dominant source for Tibetan art, were destroyed in 1203 by the Turcic invaders, Nepal remained a living source of Indic Buddhism for Tibet, as Jackson has pointed out in detail. See: Jackson 2010: Preface xi] Furthermore, the paintings from the period of the 14th century obviously show ways of representing new subject matters in a quite indigenous way, while artists of later periods were far more strictly bound to exact iconographic patterns, as Eva Allinger has discussed. [68Allinger 1997: 1380.]

Further research needs to be done on the mural paintings of the entire skor lam Yum chen mo of Zha lu to detect what still remains of the original decoration of the early 14th century and what has been added or repainted in later times. With this knowledge, the stylistic influences on the murals in Zha lu can be more clearly identified in detail.[69Because the present author found the whole monastery of Zha lu under reconstruction during a visit in August 2009, the need for further research on the “original” paintings in Zha lu, assuming that it has not yet been done, is unhappily very urgent!] We hope to return to this discussion on the Newar and Chinese stylistic influences on the murals of Zha lu monastery in a future article.