![]()

Norman A. Rubin

November 17, 2000

click on small images for full images with captions

The Mary and George Bloch Chinese snuff bottle collection

is a unique assemblage that combines the expression of artistic craftsmanship

with creative Chinese ingenuity.

(fig. 1)

Mary and George Bloch (Hong Kong) have accomplished a collector's dream. They have, within the relatively short period of fifteen years, assembled an extensive and valuable collection of one of the finest crafts of Chinese artisans - ornamental containers used for snuff tobacco during the era of the Chinese monarchy. It is perhaps one of the most important collections of these small works of art assembled since the imperial age itself.

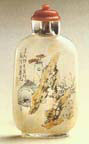

The Mary and George Bloch collection of miniature snuff bottles (1 ½ to 4 inches in height approx.) shows the wealth and taste of the last Imperial dynasty of China: from the blatantly luxurious enameled glass bottles to the understated elegance of a plain double gourd, to the jewel-like imperial yellow glass designed for the emperor only. It is truly a microcosm of Chinese art in all possible material: quartz, inside-painted glass, carved glass, jade, porcelain, and hard stone (turquoise, amethyst, aquamarine or agate). Dragons, symbolizing imperial power, homonyms for good wishes, rebuses, and calligraphic symbols of success, wealth, and longevity reflect the wishes and ambitions of the owners, "A happy life is one spent in learning, earning and yearning..." (fig. 2) The most fascinating objects in the collection of snuff bottles are those that have been painted on the inside. The painting was done on the interior surface of the piece. Glass and quartz (rock crystal) were the two chief materials, but other substances were sometimes inside-painted: agate, amber and tortoise shell. These pieces are truly amazing as it is beyond one's imagination that an artist could produce such fine work through the tiny neck of a bottle.

The origins of the themes and styles represented in the decoration of the snuff bottles go back many centuries. The inclusion of a traditional poem by the Tang dynasty poet Du Fu ( 712 - 770 AD) or a painting by the Northern Song dynasty painter Mi Fu (11th cent.) bring specific associations and meanings to the objects. As it was said, "Whoever was man was a poet and an artist." For example, symbols depicting a mythical phoenix surrounded by a crane, a pair of mandarin ducks, and other birds function as a rebus of the "Five Human Relationships" in traditional Confucian ideology.

The classic art of Ni Tsan (fig. 3) portrays the grandeur of nature, its rugged strength and tranquility; through his artistic skill he sought to unite man's being with nature, to fit the human form into the scheme of things. A painting of fish swimming lazily in a flowing stream will bring back the thought of a famous dialogue from the Warring States period Taoist Classic Zhuangzi. The dialogue between the emancipated Taoist Zhuangzi and the narrow-minded Confucian Huizi celebrates the freedom of the fish as a symbol for spiritual freedom unencumbered by intellectual and emotional baggage. Artists, such as Li Ch'eng and Lu Chih (fig. 4) sought to penetrate below the surface appearances and show that in all things we are united with the entire creation.

During the Manchu period dynasty, 1644 - 1912, the reigns of two emperors stand out as high points of artistic development- Kangxi (1662 - 1722) and Qianlong (1736 - 1795). In 1680 there were about thirty workshops that were established within the walls of the Forbidden City of Peking with the official task of producing works of art for the enjoyment of the emperor and his court. (fig. 5) The palace workshops produced magnificent artifacts - scroll paintings, silk screens, porcelain, carvings in ivory and jade, and snuff bottles crafted in various materials. (In addition, outside the confines of the palaces, there were many private workshops crafting similar objects). This continued through the Yongzheng (1723 - 1735) and Qianlong reigns, but was greatly curtailed during the reign of the Jiaqing emperor (1796 - 1820) who fell prey to the wave of foreign imperialism which brought in its wake economic, social and political ruin.

The emperors of China were avid collectors of snuff bottles. Both the emperor Qianlong and his chief advisor Heshen were known for their collections: Heshen amassed a collection of 2390 glass, hardstone and jade snuff bottles before his demise on the execution block for corruption in 1799 by the following Jiaqing emperor. Naturally, the effect that such prominent collectors would have on the production and collection of snuff bottles was immediate and powerful. The production of fine snuff bottles in all materials greatly increased to satisfy the demand by the imperial families and the numerous officials of the court - glass being the predominant material as it brilliantly exhibited artistic skill. This demand, in turn, was emulated by the upper and middle classes in China - amplifying the effect many times over.

Such bottles even became appropriate, during their time, as a type of bribe. Someone interested in an audience with a lower official would "give" him a fine snuff bottle of glass or silver; whereas in order to procure an interview with a higher official, a finely carved snuff bottle from jade, turquoise, amethyst, aquamarine or agate had to change hands.

Snuff bottles, mainly crafted in glass work, continued up to the late nineteenth century. Although the bottles are, generally, of a lesser quality, there were exceptions to the rule. Thus, there are extremely fine inside-painted glass bottles, as well as beautifully crafted enameled and porcelain snuff bottles, produced in private workshops from this period. (fig. 6)

Snuff bottles (usually glass) are still being produced in the People's

Republic of China and Hong Kong. The Chinese artists of today are keeping

the tradition of Chinese artistic skill and craftsmanship alive. These

artists, who still have something to add to the orthodox artistic customs

of the past, express it in their own highly individualistic style. (fig.

7)

|

Snuff Snuff is tobacco ground to a fine, smooth powder, and, as it is known, is sniffed up the nose. Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) is native to the Americas, and had been used there for hundreds of years by the native Indians before the arrival of Christopher Columbus in 1492. It was brought to Europe only in the 16th century by Sir Walter Raleigh. Tobacco arrived in China in the late 16th century via Spanish and Portuguese merchants. At first, tobacco was part of the tribute given to the Emperor, due to its relative rarity, but later, after cultivation of the plant was started in the Philippines by the Spanish, it became an item of trade. It was both smoked and taken as snuff.In the very last days of the Ming dynasty, from 1638 to 1644, a number of edicts banning tobacco were issued but its use was permitted again with the rise of the Manchus in 1644. By the mid 18th century, snuff-taking was a popular habit in China, acceptable in all circles of society. Indeed, it was even encouraged at the Imperial Court.When tobacco snuff was first brought to Asia, it was carried in wood and metal snuffboxes. It soon became clear that the humid climate of the area was damaging to it in such containers. The Chinese found a solution to the problem through the use of small glass medicine containers (and a tiny spoon), and converted them to snuff bottles. This in turn started a new artistic expression that utilized luxurious materials for the vessels to satisfy the whims of the emperors and their court. |

REFERENCE:

1) Catalogue, "Whiff

of Luxury": Chinese Snuff Bottles from the collection of Mary and

George Bloch - Israel Museum, Jerusalem Curator, Rebecca Bitterman.

2) Inside-painted Snuff Bottles and Classical Traditions of Chinese Painting (Catalogue - The World in a Bottle) - Stephen L. Little, Pritzker Curator of Asian Art, Art Institute of Chicago.