My research

The topic of my research is traditional Tibetan themes in painting and the possibilities of expressing and relating to them in my own painting style within a contemporary art context.

Background

Childhood

My childhood years, until I was seventeen years old, were spent in the city of Shigatse, the second largest Tibetan city at the time. My family house was located to the north of the ninth Panchen Lama's family house and to the south side of the family house of the tenth Panchen Lama's; together the three houses formed a perfect triangle.

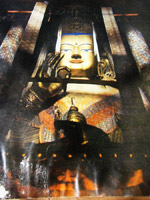

My maternal grandfather, Nyariba Sonam Dhundrop, was a great artist (chemowa) in the palace of the ninth Panchen Lama, and also at the Labrang (the government of Panchen Lama) official. According to my mother, her father, who was usually working at home, did not care much for office work. When it was decided at Tashilumpo Monastery to mould a huge statue of the future Buddha, many designers of bronze statues were summoned for the task.

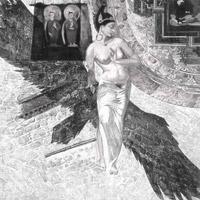

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

However,when the project proved more ardous than anticipated, as many unforeseen problems arose, the ninth Panchen Lama personally issued an order for my maternal grandfather to come to the monastery and take charge of the designing of the work. The request resonated deeply within the artist's pious heart, who thought the occult meaning of the event was a deity revealing his life direction to him. Thus, from then on, he lived at the monastery, working diligently around the clock, just barely resting for the meals his elder son brought him every day. For the design of the 26.7 meter high statue, he used eleven huge Indian bags of traditional Tibetan papers. Upon compeletion, it was the biggest bronze statue of the future Buddha (Tib. Chamba, Sans. Maitreya) in the world (fig. 1), and since then my grandfather worked with design for the rest of his life. It is also as a designer his name is honored by posterity. There are some pictures of four kings painted on the entrance wall of Chamkhang (the temple of future Buddha), of which one, the King of the North (fig. 2.), is painted by my maternal grandfather.

My paternal great grandfather was a Tibetan traditional painter, whose speciality was illustrations of deities. Once when still a boy, he was walking by the Nyangchu river side where he found some traditional painting brushes. This he interpreted as the deity pointing out his future direction, and he committed his life to art. Even today we can see his works in the halls of Lhasa's Jokhang temple.

Perhaps due to heredity or possibly because of the influence of my childhood family environment, I really do not know, but I have enjoyed painting as long as I can remember. When I was young, my mother used to bring me with her to the Tashilumpo Monastery's traditional publishing house, where my uncle was director. In his chest of drawers I found numerous drawings and paintings that he himself had made of charcoal. I would sit there, totally absorbed in the drawing of flowers, birds, fish, yak, and deers till the sun went down.

I have a vivid recollection of a sacred room with a filing cabinet, on it stood a picture of a monster (wrathful deity) that I have never seen the like of to this day; I was overwhelmed by the image of sheer terror and panic. It was painted by my paternal grandfather, who painted many strange and distorted animals that of course were all images of deities or ghosts. For example, an image would have a tilted head with horns and a black beard, white eyebrows, and pink skin; and a body like a human torso with feathered wings. During the Culture Revolution, all these old possessions, pictures and other items, of my family disappeared.

Once during the Culture Revolution, I was in a warehouse where books were collected, and found the treasure of some handed in comic books.

At that time, all books with pictures of religious imagery were categorized as harmful. Still, a childhood friend and I managed to carefully procure some tattered copies. Although in a pitiful condition, stories of deities abounded, so I imitated all of the pictures, until there was not a scratch of paper left in my home.

I was always hoping to find new interesting things to do or games to play. Once, I had found the hide of an Indian animal, which I cut in two circle-shaped pieces and left to dry in warm horse dung for two days. Next, the pieces were washed and pressed between two heavy flat stones for two days. The last step was to transform them with colours into multi-coloured material which served as excellent pads for playing sho, (fig. 3) dice (fig. 4) as well as other games people used to play.

Looking back, I think I must have been quite an inquisitive kid in my early years. After homework, I was always on the look out for new activities whereever I could find them. My mother's chest of drawer was an item of great interest. Once I procured some yak cotton and sixteen or thirty-two lengths of multi-coloured thread, which I braided together (wordo, fig. 5) to make a slingshot for pebbles, similar to those used by sheep herders to control livestock.

Another time I used red and white coloured sandalwood to make a tobacco pipe for our neighbour, a very kindhearted old man.

A much enjoyed activity was the painting of playing cards. This proved very popular, since at that time, only a few Nepalese possessed this highly acclaimed treasure. I tore up some wrapping cardboard and carefully cut out fifty two pieces upon which I drew elaborate pictures and numbers. I recall that one of the decks was exchanged into twelve silver bells.

Of course, I did not have any understanding of the definition of art at the time, but I was often making illustrations. My father, Menkyi Sonamdorje, was a scholar in Tibetan language and history, and a very responsible father of a big family. I never saw him angry at any of my siblings, nor did he ever lash out at anybody. My mother, Menkyi Tsering Yudron was a very hardworking house wife and a pious Buddhist. Whenever she went to the monastery she always brought me along and she gave me strict instructions on how to conduct myself. Before the age of eighteen, I had never seen nor watched TV. To me, the intuitional ideas and imaginations of my childhood are always valid, just as much within the sphere of concrete thinking and logic as in the images of conceptual art. All the various expressions have relevance within the wider frame of cause and effects, karma, rebirth, and evolution, all interweaved in the abundant Buddhist stories my mother told me in my childhood.

Studying hard at the university

After finishing high school, I was, together with peer students, sent to rural districts to work on farms. In 1976, however, the college entrance system was reestablished after the end of The Chinese Cultural Revolution. I was admitted at Tibet University, where I studied concrete art and the disciplines of sketching and landscape painting (figs. 6,8,9.) My graduation work Horse Race (fig. 11) was exhibited at the Fifth National Youth Exhibition in January1980. While studying oil paintings at the Tianjing Academy of Art, I specialized in nude paintings (figs. 12, 13, 14, 15, 16). In 1981, my graduate work Hope was bought by the Sixth National Art Exhibition. It is an illustration of a young mother in a pastoral area, concentrated on the making of a writing implement for her son. She pins her hopes for the future on her son, who brings his writing board with a sweet smile to his mother (fig 19).

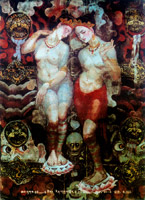

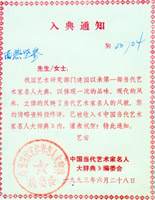

After returning from Tianjing to Lhasa, I devoted myself to the realistic style of painting in order to illustrate the life of Tibetan country people (figs. 20, 21, 22, 23, 24). The Farm House was accepted by the Second National Oil Painting Exhibition; The Work of Tibetan Women by the First National Minority Art Exhibition. The Goddess in the Sky (fig. 25) was accepted by the First National Exhibition of Water Colour and Chalk Painting, which praised me as 'a renown Chinese contemporary artist' (fig. 26).

Inspiration from Overseas Travels

In 1990, I traveled for the first time to a foreign country and visited many museums and galleries. Once, through a temple door frame, I saw a statue of a protective deity stepping on a heap of human bodies very similar to the pictures hanging in Tibet's Sakya Monastery's south building. One of my friends told me that in the past a western Buddhist nun had visited the temple, and upon seeing the deity's stomping on the bodies, had made the interesting remark to the presiding monk (nangba):

'Ai! Oh, my! The Buddhists are exceptionally merciful, but why is the deity trampling on people. Isn't this very brutal?'

'You know', said the nangba,' the deity is not stepping on a real person, the image symbolizes a person's ego and the demons haunting the humans. If wicked ideas are not uprooted, the three poisons of the mind can not be extinguished', whereupon the nun and the nangba bowed to each other in perfect agreement.

To me, this conversation was enlightening indeed. If the images of distorted monsters and victims represent people's egos or demons (frequently the same thing), the different illustrations of wrathful deities only reflect various ways of taming human consciousness.

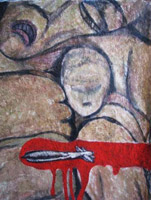

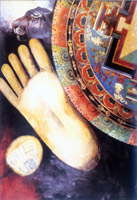

Fig. 27I decided to paint the topic (fig. 27), but more specifically, to paint the image of humans grappling with their demons as seen with my 'mind's eye', and, to the best of my ability, express the essential spirit of a culture in the aesthetic language of art. Enhancing the quality of mercy through abandoning viciousness by the tool of conceptual art requires both creativeness and educational skills. However, concepts and ideas are different; while the former implies a general direction, the latter is a mere component. In this sense an idea implements the concept. I think conceptual art needs the background of the individual spirit in order to touch the human heart, a capacity which ideas do not possess, although they are powerful triggers for personal response.

Whenever I visit a monastery and look at the intertwined center animals of the pig, the rooster and the snake in the Mandala of the Wheel of Life (sit ba khor lo), I contemplate these three, representing the evils of ignorance, greed, and hatred, as the causes of all human suffering. Yet, if we would but be willing to renounce the three poisons of our being, human kindness will instantly be restored.

Returning to Tibet, it proved very fortunate that I had been studying Buddhist causality and psychology, as Geshe Tsewang (a Buddhist master and previous monk in Tashilumpo Monastery) started teaching at TU in the early 1980s. (He passed away in Lhasa in 2006) Although this period was short and lasted only two years, I gained a deep knowledge from him. Since then I have had many opportunities to enhance my Buddhist knowledge, and I have come to realize that Buddhism is both an elaborate system of spiritual science, and a wonderful expression of art.

Once upon a time, there were two mountains. On their respective peaks, there lived a monk and a butcher. The monk was, at least apparently, a pious Buddhist, practicing Dharma and daily meditations. On the other summit, the butcher was slaughtering sheep every day. One day he could not find his butcher's knife. Looking for it everywhere, he still could not retrieve it, because an old sheep had hidden it under its belly (fig. 28). In a moment of clear insight, the butcher suddenly grasped the sheep's predicament. Deeply regretting his evil deeds, he jumped from the precipice to kill himself. However, because he had changed his ways and taken to virtuous ideas, he soared to the sky.

From the other peak the monk had been closely watching this, and he was thinking to himself: 'Even the criminal butcher was taken to the heavens when he tried to kill himself. If I, a pious monk should jump, I would surely be lifted to the skies.' Thus, assured of his high status as a meditating monk, he swiftly jumped from the mountain side. Yet, because the monk had taken to vicious and jealous ideas of superiority and conceit, he plunged to the ground and died immediately. (fig. 31)

There are countless ways to meditate in Buddhism. One is called 'The Middle of Sequential Meditation' (gom rim pra ma ).

In order to practice this meditation, the first step is concentrating the mind like a non-flickering oil lamp on the concept of happiness for all living beings. Next, thoughts for the well being of humans are cultivated and imagined to the practitioner's right side, and to his left side, the well being of all sentient beings is focussed on. Then, the practitioner imagines an enemy or opponent in front of him/her, and suffuses this person in feelings of compassion. Consequently, harmful influences are diminished, both within oneself and in your opponent, and all life forms benefit in terms of spiritual protection.

All sentient beings are connected, and all life will eventually be released from the suffering of earthly existence. According to tantric view, no matter how elaborate the skills people have developed, the paramount idea is the virtue of compassion. This is why pious Buddhists frequently recite the quintessential mantra of compassion:

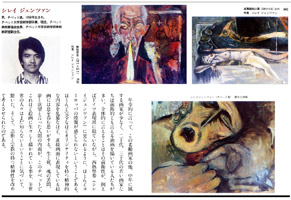

In October 1992, three of my pictures were displayed at The Symphony of Soul Exhibition in Tokyo. At that time, some Japanese art critics became interested in my works, especially Mr .Junichi Fujiyama, chair of the Japanese Center for Visual Arts, who commented on my works in art collections and magazines where he once wrote: ' Sherabgyaltsen's paintings are both rough and direct in their conveyance of spiritual content, their originality of expression leaves me breathless. I am surprised that the international community does not pay more attention to the vivid demonstration of the interplay of life and death in Tibetan paintings, the experience of the soul of the deceased and the longings and desires of the human nature. This could lead us to reconsider the art of spiritual and religious motifs.' (fig. 33)

Another comment on my works in an art collection reads: 'One of the young artists is Sherabgyaltsen. When I first saw his paintings, I believed them to be imitations of German expressionists. However, upon a closer look, I feel his works express spirituality very directly in a uniquely vivid and rough way. When compared with German Expressionism, the content has a totally different flavour. And additionally, German Expressionism is closely connected to Christianity, while Sherabgyaltsen's paintings deal with the Buddhist ethos. There may be some similarities though. Sherabgyaltsen's art may not possess the polished restraint of German Expressionism, but it directly conveys a deep and serious passion. He has developed his art to the degree where he is not only a renown Chinese artist but also an artist of religious paintings at an international level.' (fig. 34)

The next year my work All Beings Seek Bliss and Shun Suffering (fig. 36) was displayed in Japan in The 93 Tibetan Paintings Exhibition. In 1992 Support a Beautiful Sound (fig. 37) was displayed at an exhibition in Taiwan.

In 1998, one of my water colour works was displayed after an invitation from The First Macau International Art Exhibition (fig. 35)

Since the chair of Tibet's Artists Association was very dissatisfied with the Japanese evaluation of my works, I withdrew my membership of the association, which also barred me from further participation at exhibitions. In 1998, however; The State Council Information Office invited me to send seven paintings to the exhibition Contemporary Tibetan Paintings in Beijing (figs.29,31,36,38,44,45,46) I was also granted a certificate from this exhibition. (fig. 37)

In 2003, The Concept of Worldly Love (fig. 43) was displayed at The Third National Chinese Exhibition of Highly Acclaimed Oil Paintings.

With few exceptions, I mainly painted Tibetan life in realistic style since 1977.

After 1991; however, I started focusing on Tibetan art centered on religious motives and characteristic features of Buddhism. Buddhist religious virtues are not only a very interesting topic for me in terms of personal life philosophy; they are also a rich source of inspiration for my paintings. But I like using contemporary art styles for the painting of Tibetan traditional themes.

As the origin and center of contemporary art is in the western world, in order to penetrate its mystery and also to further develop my own art expression, I had a passionate dream of going to the west to study modern art. Therefore I started to learn English, and fortunately I met my English teacher Ragnhild Schea by whose encouragement I obtained a scholarship for a Master degree in art.

This was the foundation of my study in Norway, where I feel my dream materialized, and my artistic vision truly expanded by the horizon of new concepts and approaches to the perception of reality.

Eastern and Western Art Education (New ways of learning)

The way art is taught in Tibet University differs tremendously from the art pedagogy in Europe. In Europe, I think, the greatest values of higher education are the students' own theories of expression and the individual artist's imaginative faculties. In our country, however, only skill matters. It has taken me a long time to adjust to that. For example, when meeting with my supervisor, I always hoped I would be advised about the further steps in my work, because without the process of working according to the premeditated steps that avail in my background, I would be at a loss about its development.

Process and Research

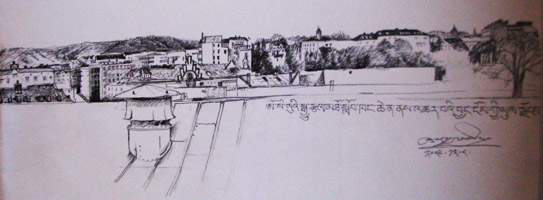

I have been studying in Oslo for about two years. During this time I have visited galleries and museums in Berlin, Copenhagen and in Venice I visited the Biennale of Venetia, studying both classical and contemporary art. Together with my supervisors I have discussed the content of my research, and I have taken part in forums where students presented their work. Gradually the choice of my own topic matured.

Ever since the first time I saw Edward Munch's art, his pictures have always been a great inspiration and have also triggered a lot of passion in me. In Oslo I have been mesmerized by seeing his original works. People have often asked me why I like Munch's works so much, a question I found very difficult to answer. However, after much deliberate thinking, I have gained some insight into my fascination by Edward Munch.

In his works, he describes his personal anguish about love, life and death in highly simplified forms. For example are The Sick Child (fig. 55) and The Moonlight steeped in an atmosphere of a repressed inner world by the dramatic focus of the painting. When Munch portrays his entire family, all the members are dispersed in a series of separate and disconnected figures of sorrow, emphasized by Munch's use of shadow and color to highlight an aura of fear, menace and anxiety. These are all aspects of a very important part of life according to the Buddhist point of view, one of the expressions of the Four Noble Truths (catvāryārya-satyāni); the truth of the suffering of life (khār-yasatya du). Munch's art tells about this powerful part of human life more vehemently, more directly and more passionately than in any other pictures I have seen. His art is like a mighty confirmation of Buddha's truth in color and form. This is why I appreciate Edward Munch's work.

Abstract art and Tibetan religion share many similarities; for example, both make statements about impermanence. As life is primarily about change, physical manifestations of designs and shapes are constantly dissolved and reformed. I feel this transitory aspect of life where nothing is permanent, nothing lasts, but everything is a state of perpetual flux provides me with a vast open space which gives me unlimited freedom to paint.

My History/Culture in a Contemporary Context

I often ponder whether I agree that all the ways of creative expressions that I see at the art academy in Oslo is really art. While continuously improving my art forms, I feel they are deeply rooted in my life and cultural background: My childhood was composed of listening to my mother's stories, attending school, and doing farm work. Everything that happened in life was connected to Tibetan traditional culture, and it is my aim today to incorporate my cultural background in a contemporary context. I consider the two years of studying here as a time where I try to build a bridge between my Tibetan traditional culture and the work of contemporary art I have seen in various galleries in Europe.

My Creative Process

Since I came to Oslo, I have enjoyed the impressions of beautiful city scenes in harmonious plays of colour. Mentally I always compare Norwegian weather, colours of nature, people and society to life in Tibet. Of course, being an artist I am interested in the visual perceptual properties of colour. In Tibet, all four seasons have abundant sunlight; the sun shines annually almost ninety percent of the time making intense colours, and Tibetans like wearing clothes in the bright primary colour tones. The weather may vary several times on a daily base, but here in Oslo the colours and the weather are more soft and stable and the colours appear to be in a quiet harmony. I unconsciously nearly always use bright primary colours in oil paint when I paint Tibetan nomadic figures. However, my perception and use of colour has changed since I came to Norway. Here the colours do not appear as bright as in Tibet. This was my first impression of the differences between Norway and Tibet and is still a fond memory of my first meeting with Norway. (figure 56, 57)

As my use of colour has changed, so has my subject matter. Although my interest in Tibetan Buddhist stories remains unwavered, the style and context in which I work are different today from when I came to Norway. Although always deeply interested in the essential meaning of Tibetan stories and religion, I now transmit the stories differently. In Buddhism the thousand armed Chenrezig (Avalokiteshvara) is a merciful bodhisattva who helps all sentient beings to liberation from suffering. My paintings are usually based on, or inspired by Tibetan Buddhist stories and sutras, and Chenrezig is my inspiration for The Figures in the Swamp. In the foreground the figures in the swamp with televisions on their heads are symbols of human self-centredness. Immersed in their own difficulties they lack the capacity to help each other.

In Buddhist view, the people in "swamp like" or difficult situations never rescue anyone from danger nor ease anybody's pain, as humans first must adhere to the Lama's (Buddhist teacher) teachings in order to abandon their own selfishness and do something for other people. In Buddhist perspective everything is interconnected throughout the aeons of time, and everything has cause and effect. The thousand armed Chenrezig symbolizes unlimited vision. The televisions on the figures' heads are symbols of modern times. Being imprisoned within our delusions and warped thinking, we are desperately in need of rescue. Yet, the one thousand armed Chenrezig can only reveal the path of liberation to us. Like a doctor prescribing medicine he can not force it down out throats; there is always free choice. The televised figures in the swamp are too absorbed in their own delusions to feel compassion for others. (figs. 59, 60)

The background of the picture is a lecture I attended on Buddhist causality in Lhasa years ago. While listening to the enfoldment of the story, a picture formed in my mind; a visual expression of personal anguish and inability to change, expressing the ignorants' road to suffering and ruin.

When painting People in the Swamp years later, the creative process was different from how I normally work from models or photos: Instead of being a clear image from the beginning, the picture seemed to spontaneously unfold from my mind. I read in Sentences on Conceptual Art that ideas not necessarily come in logical order, but rather divert in unexpected directions. This is an apt description of how I felt while painting People in the Swamp.

Different people have commented that the picture reminds them of the work of the Danish artist Michael Kvium. It is fascinating that people have recognized similarities in Kvium's and my works, I was even asked whether I had copied his work. The truth is, I had never heard of the artist nor seen his pictures before after completing People in the Swamp. Seeing Kvium's pictures on the Internet, I too was surprised by the similarity of his picture and my painting. Although both culture and artistic backgrounds between Kvium and me differ tremendously, the pictures are similar in expression, albeit not in meaning.

In my work I seek to make a link or bridge between traditional Tibetan thanka painting and western art, something I feel is a tremendous challenge. However, I was satisfied with "Skulls". In Tibetan folklore, dreaming about skulls brings good luck; stories abound about skulls and the ensuing good effects from their appearance. For example, when a monastery holds a religious dance, skeleton figures usually appear as an important part of the performance as they are believed to help sentient beings in life and death. (figs. 61, 76)

Following my supervisor's advice I continued to modify my work on the hat and the strange dark green form in "Skulls" till the picture became harmonious. (fig. 76)

At the very beginning of my art, I did not make any sketches; I just painted directly on an old painted canvas following my natural instinct. In hindsight, I don't know if I created or destroyed art. This process of working is very different from how I usually work today.

"Greed" is an attempt to merge contemporary human experience with traditional timeless Buddhist values and beliefs still relevant today. In the symbolism of the Tibetan wheel of life, the realm of the Hungry Ghosts is the state of neurotic desire. When is desire neurotic? Desire is neurotic when it seeks from its object more than the object by its very nature is able to give or when even different satisfaction from what the object is able to give, is demanded. Let me take for example the neurotic desire for food: Sometimes people gobble down huge quantities of food, especially sweet things, while their needs are about anything but food, which has merely become a substitute for a deeper need. Psychologists claim that people consume unnecessarily large quantities of food for psychological reasons. Especially is the craving for sweets essentially a need for affection. Neurotic desire in this sense is also very often present in personal relationships; particularly in intimate personal relationships to such an extent that it appears that one hungry ghost is trying to devour another. That's the Pretas', the hungry ghosts', state of mind. (figs. 62-66)

Being very interested in the inner world of human nature, in this picture I have tried to express a feature of the human character I have noticed over time. Some people appear to be very afraid and always angry, but their inner world is very kind, much like the way parents relate to their sons and daughters or like the teacher-student relationship in a Tibetan monastery where teachers never smile with students but at an inner level care deeply for them. In society the theme is reflected in many social relationships; sometimes people are good at pretending wisdom and kindness, but their inner world may be different. By judging from appearances alone we do not understand the inside quality, but are mesmerized by surface glamour and think "what a good heart this person has!" In my paintings I use unusual situations in the foreground while the figures and their shadows are different and act as symbols of the dual character of human nature. In the corner at the background is a symbol of the Buddhas' and bodhisattvas' encompassing understanding. (fig. 69)

Chenrezig (Avalokiteshvara)

Tibetan religious paintings, known as thanka paintings, are an intrinsic part of Tibetan art. They depict different religious personalities and manifestations of the Tibetan pantheon. Chenrezig, the embodiment of compassion and the savior of Tibet, is one of the bodhisattvas whose singular mission is to save all sentient beings. He exudes impartial compassion for all creatures simply because there is no living being that has not once been one's mother or father. As all life forms are interconnected, the taking of a sheep or a goat's life is tantamount to committing matricide or patricide. Wielding the compassion of all the Buddhas, Avalokiteshvara has vowed not to rest until his mission of universal salvation is achieved. (figs. 70, 71)

- Thanka, in the Tibetan language, means something that rests on a flat surface.

- Thanka is a traditional form of painting dating back to the 7th century when it originated in India along with Buddhism.

- Thanka incorporates influences from the neighboring Buddhist countries India and Nepal. It is also influenced by Tibet's indigenous animist Bøn religion.

- The subject of thankas are Buddhist stories that depict deities, Buddhas, bodhisattvas etc.

- Thanka painting has many distinct style periods that have evolved over the centuries.

- Traditionally, thankas are not secular paintings created for galleries or museums, but a religious tool used primarily by monasteries for conducting life according to the Dharma. (The rules and regulations for leading a Buddhist life.) Today, they are also collected as "art".

- Traditionally, thankas are commissioned by families in memory of a deceased (dead) family member. The family offers the artist money, butter and barley. Monasteries often commission larger thankas. (figure73)

- The thanka artist is often a monk living in a monastery but can also be painted by laymen (not monks). The education for thanka painters extends over many years, during which the student traditionally lives with his teacher.

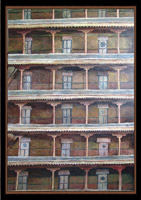

Thankas are usually scrolls painted on long rectangular pieces of un-stretched canvas mounted on traditional satin fabric. The most valuable fabrics are embroidered with pearls. The scrolls are portable, designed to be easily transported from homes to monasteries.

Thanka painting has many rules and conventions in respect to composition, color, and subject matter. They are read clockwise, from the top left-hand corner with the most important figure(s) placed in the center. Usually they are clear and easy to understand by anyone familiar with Tibetan subject matter and Buddhist iconography (symbols). Moreover; they enable illiterates to understand Buddhist stories by simply looking at the thanka motifs. There is a clear distinction between foreground, depicting Buddhas and other deities, and the background with mountains, stones, clouds, trees, and palaces.

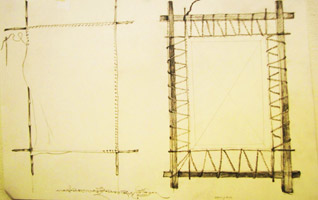

Fig. 72

Fig. 73The process of making a thanka involves first stretching canvas on a removable frame (fig. 72). Then follow the sketching of the lines of the background and figures that have very exact proportions. The artist then grinds pigments from minerals and stones which are mixed with glue to make long lasting paints. Pure gold is also used for the making of paint. When the painting is completed, it is sent to a tailor who fastens the thanka to fabric (often silk or brocade). The process can take from a week to several months to complete. There is also a one-day-thanka commissioned for special occasions. The students study four years to become thanka painters

Acrylic paint was first imported to Tibet in the 1980s. Today, many contemporary painters use acrylic color in Tibet. I find it very easy to combine line drawing with the brush strokes of this media. In my work, A Small Butter Lamp, I used acrylic color on canvas. The idea for the painting comes from a Tibetan story about the Buddha and a devout old woman with a strong belief in Buddhism, who greatly admired the beautiful light of the butter lamps offered by rich people for the Buddha in the monastery. Because she was poor and didn't even have enough money for a single lamp, she decided to beg for money on the streets. Having spent the whole day begging, the money was still insufficient. However, when the shopkeeper found out the butter was for an offering to the Buddha he still gave her some for the small amount of money. Upon receiving the butter her heart warmed and she quickly ran to the monastery to light a lamp for Buddha. The small lamp was burning day and night. A student of the Buddha saw the light from the lamp and tried to put the flame out, but it could not be extinguished. The student got humbled by the Buddha's words that even if all the water in the wide ocean was poured over the little light lamp it would not be put out, because its flame comes from deep within the old woman's heart (fig. 77).

My portrait study is based on the famous South African artist Marlene Dumas's works. Although my painting of portraits can never reach her level, from beginning to end I am fascinated with her works. I also realize that I lack what she refers to as painting from an erotic display of mental disorder. Although there is much beauty in her portrayal of children and women, they always seem somehow uneasy. Her works are full of people showing the usually easily overlooked phenomena of characters with a sense of impurity. I appreciate Marlene Dumas's use of her excellent painting skill to portray and express these issues without tabooing motherhood, virginity, racism, sexuality, and religion with a strong sense of terror. At the same time my traditional conservative ideas are incompatible with the torture which, placed in this context, has no place in Tibetan culture.

I am writing about these two paintings because I want to speak of myself (figs. 78, 79). My intention when painting the young man was to imitate the work of Dumas. I found it very difficult. I first saw Dumas's works in Lhasa in an art magazine and felt attracted to it for long time. I feel her portraits are not only technically skillful but also transmit a very cheerful and relaxed mood. I was very fortunate this year when my supervisor arranged a trip to Venice to visit the Biennial, where I could study Dumas's original works. They are very beautiful and it was also interesting to experience that though all of her paintings first appear to be quick sketches, they are quite elaborate work on closer observation. I realize that my painting will not be admitted into the world of genuine art if I only paint realistically without expressing my inner emotions. Therefore, I continue to learn a lot from studying contemporrary art that I am interested in.

I first tried to do the portrait approach of Marlene Dumas's style of refined brushstrokes. Perhaps because our starting points are based on completely different points of view did I find it interesting, but difficult to imitate her works. The essential point is the face's character, which is why I took great care in the portrayal of the face by a small brush, using very light strokes on the area under the jaw and the cheerful and relaxed textiles, especially the eyebrows. In Tibet, the young actors in traditional drama often paint a thick line in their faces for eyebrows, which is where this idea comes from. But I think many famous works often use this style, in particular in motifs related to opposite ideas of emptiness and reality, or tightness and looseness.

Marlene Dumas' emotional involvement with the subjects, coupled with her distortion of the original photographs create unnaturalistic renderings with a characteristical haunting edge. An amusing thing is that while trying to copy her, I still painted it in the realist style; both content and colors are connected to the natural world

This picture was a gift for Mr. Knud Larsen's seventy year birthday. In this tie, my three different styles of art are included: The early years of realistic painting of Tibetan life; in the middle part the focus is on Tibetan art in Buddhist style centred around religious motives, and finally, during my stay in Oslo my new style with the roots series and people in the swamp emerged. (fig. 81)

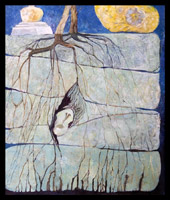

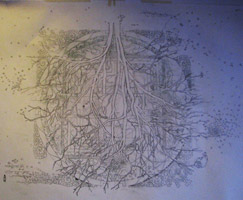

I began painting roots in my work in 1999.(fig. 92) When roots become a subject in my paintings I thought of it as meditation. It is claimed that every individual has different experiences when observing a mandala. However, the overall consensus is that meditating on the mandala form leaves the observer relaxed and with a resolution or clarity concerning the topic that occupied the mind before the meditation. The mandala symbolism gives me endless inspiration, as roots in my idea associates with the pulsation of life in living beings; they are the human veins and the thin lines patterned in leaves and in the wings of certain insects. It's a very animate symbol which can provide artworks with a dynamic quality.According to Tibetan medical science there are four primary elements and one direction: Earth water, fire, air, and space. When one of these becomes imbalanced, the physical body (any living body, both animate and inanimate) becomes sick, and can only heal by the restoration of balance of the four. The yellow colour symbolizes the earth and northern direction, white stands for water and the east, red symbolizes fire and the south, and green represents air and the west. Meditation is exercising the mind in order to strengthen the soul, and this strengthening is symbolized by the symbols of the mandala and roots.

When I contemplate the trunk and roots they remind me of the west and the east door of a house, like when I first saw the buildings of Oslo National Academy of Art and the National Gallery. I did not think the gates very impressive until I came inside, when they were perceived as entrances to vast and endlessly extending mystery houses. In my country the gate is a symbol of power and reputation. Many administrative structures are not so big inside, but are built as luxurous and impressive entrances much like how a personal villa is broadcasting wealth. Comparing these different attitudes in the two cultures gives me new ideas as I continue paiting roots. I think the door is like the trunk.The trunk is what we see above the ground but the roots are hidden beneath the earth and give the tree life. This is important to my work and I take great care to portray roots, which recently have become a great fascination for me. I have changed material and the background shape of the madala; in this mandala all patterns are in the shape of Vajra (= Dorje in Tibetan which means instructible, diamondlike). With the dorje pattern inside the mandala it is a powerful symbol, which is perhaps why I feel it pulls the viewer into the work. (fig. 90)

The meaning of mandala comes from Sanskrit meaning "circle" based on its concentric structure. Symbolizing unity and harmony, mandalas offer the balancing of visual elements. The meanings of individual mandalas are usually different and unique to each mandala. Symbolizing cosmic and psychic order, the purpose of the mandala is to serve as a tool on our spiritual journey.

This rough water colour painting is an illustration of a Tibetan folk story called:

"A Dog Pulling a Horse and a Fox Wearing a Hat"

Once upon a time there was a couple living in a tiny village. The wife found that her husband didn't like to go out and do anything, but was always lying in bed. She said to him: "You must go out and take part in the outside world; a man who stays all day inside the house will not have any prospects". But the stubborn husband was adamant. One day she hid a big box of butter in the grass of the field. Upon returning home, she called her husband and told him that if he didn't like to go out, at least he could climb the house roof. This time he agreed and from the roof he immediately saw many crows scurrying about the field. He thought this very interesting, and hurried out to learn about the cause of the commotion. In the grass he found the big box of butter. Consequently he thought his wife was right; a man should go out and get new experiences. Thereupon he took the butter and went home, making a great show about being a man of ability.

The next morning, he decided to go hunting and grabbed his horse, dog and arrows. Riding briskly through the grassland he saw a fox running into a hole. He tied his dog to the horse's leg and fastened the bow, arrows and bags to the harness. Then he took off his hat and it put over the hole, and started jumping up and down on the ground beside the hole. When the poor fox panicked and ran out with the hat on its head, the dog immediately sat off after the fox, and the horse had no choice but to follow the dog. The man of course, had to run after his horse. After a long time he asked people if they had seen a fox wearing a hat and a dog pulling a horse. People thought he was crazy, and nobody paid any heed to him. Then one night on a hilltop a gangster robbed him of all his clothes. Having walked naked and hungry all night, and finally arrived in a city where he tried to rest in a pigpen. The big boar did not like him, and would not let him sleep. At dawn he spotted a palace in the distance, and as the sun was rising, a princess came out on the palace roof. Washing her hair she dropped her earring which bounced along behind a cow. Cow droppings fell on the earring, and a worker coming along took the dung and fastened it on the wall to dry. (In Tibet people use dry dung for fuel) The princess never understood what had happened, but the man watched all this carefully. In the afternoon, the whole city worried about how the princess had lost her earring. People saw the man without clothes and, thinking he was a fortune-teller brought him to see the king.

The king asked him if he knew where the princess's earring was. The man promptly retorted that he knew the ring's whereabouts, but in order to help retrieving it, he needed the king to do something for him first: "I can help you to find it, but first I need the head from the big pig in the pigpen near the palace". When the pig head arrived the man pretended to do some sort of fortune-telling ceremony, whereupon he led the king to the spot on the wall, where the dung was. He counted the dung cakes and finally chose one, which he asked to be opened. When the earring was found, the king became very happy and gave him many treasures and an army division to bring home with him. (fig. 89).

The story is from an old Tibetan folk tale, with altogether twenty one chapters. The narrator is a corpse talking to a boy, a situation which looks bizarre upon the first gaze, but becomes clearer as it develops and comments on the illusion of life and death, confirming that death is just a transition period from one life to another. I find the tale very interesting. A long time ago, I painted two large size pictures of motifs from this tale (figs. 86, 88), and I plan to continue to paint the Tibetan ancient generations as rendered in the folk tales. I believe these motifs could provide a link to contemporary art.

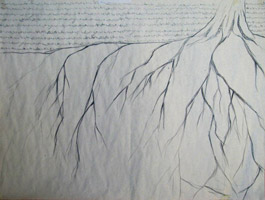

In visual art oil colours always give strong impressions. But in painting sometimes change of material is possible. In my recent work Creating a New Mandala I only use paper and pencil. Although I think there is a lot of repetitive work in painting, this can also lead to the emergence of new impressions.

In the same way a simple colour can leave the viewer deeply impressed.

In my second work about roots and mandala work I still use pencil on paper. Countless letters of many alphabets coming from mazes' roots weave their movements into a conditional Tibetan Buddhist mandala.

These two totally different artistic forms are here brought into harmony. I was wondering how the image would change by adding a person into it. Inspired by the notion in "Sentences on Conceptual Art" that irrational judgements lead to new experiences, I have drawn a small figure in this work which proved to be totally necessary. I think there is a difference between a portrait and a picture of any face or figure.

In the picture Mandala and Roots II (fig. 94), the spectator sees a small figure which is like a mark in the letters of the alphabets. The figure could lead the spectator to connect impressions in the mind in a new way. But maybe the figure in this picture is not harmonious. I think different figures bring different contents to the mind. When seeing the portrait of a figure, we first think it looks like someone we know, or else may express different meanings. Depending on the angle from which the figure is seen, it will be perceived differently, for example, it can be experienced as a person in the picture looking at something. How it is interpretedn depends on the content of the artist's mind.

In the third Roots and Madala picture (fig. 97), the hands of Tara, the fire and the palace in the circle were painted in Tibetan traditional thanka style. Moreover, I have still painted roots, although now the roots are reversed. In Tibetan monasteries, the monks carefully make sand mandalas before religious celebrations. When the rituals are completed, the host lama destroys them with the stroke of a brush as a recognition of and tribute to life's impermanence (fig. 84). I see this basic topic reflected in numerous works of contemporary art. My recent works are based on this idea, which I think is one of the pillars in the western works of art; the courage and ability to change. Around the circle I have painted birds, kites and spheres which are flying freely in boundless space. The design of the sun and moon symbolizes luck and auspicious events in Tibetan traditional culture. In this painting I have changed material from watercolor to pencil on paper. My supervisor asked me again, like she did first after I had just arrived in Oslo, why only about half of the birds are drawn when everything else in the picture is meticulously painted in full shapes, making the traditional Thanka motif appear incomplete.The reason is that when I drew the external forms like the moon and half birds, I only considered the form of the moon, without paying pay attention to whether the shapes of the crowd of birds were complete or incomplete. Unconsciously I have used traditional Chinese birds and flowers in a freehand style, which is half motif and half empty paper.

The universal principle of cause and effect is deeply rooted in Tibetan thinking. Life is like a cosmic loom, and everything is linked through connective threads. The dualistic laws of life apply to all life forms; everyone has times of happiness and times of suffering. All that happens are effects from actions done somewhere in time, which are made from still other effects, creating a chain of personal causes and effects stretching over eons of time, and many, many lifetimes. If, in this or in past lives a person does something good for other sentient beings, positive effects are created. When time is ripe, the person will experience happy effects from the good actions. The loom is always weaving its threads in accordance with the colors it is given, selfishness creates more selfishness, altruism makes more altruism.

Everybody suffers from, and has to deal with the negative effects from past actions, but one can still prepare for a better future life by actively contributing to other people's happiness.

There's a Tibetan idiom which says that the life situation in the present life reflects the past life and the actions of the present life predicts the future life

It is important to live in accordance with the karmic law in order to create better lives for all. Life is an unfoldment of people's understanding of this law.

I am drawing roots and mandala motifs because these symbols represent for me cause and effect. For example, when the soil, water, fertilizers and weather conditions are all in harmony when the seed grows, it will bear strong fruits. Likewise, when the harmonious blend of the earth, fire, water, wind and space circulate in humans, they too are strong and healthy.

When people realize that the law of karma is very important, they will also take responsibility for creating better future. In my works of mandala and roots, the mandala symbolizes the human body as form, a vessel, while roots are veins, the content of the vessel. Through exercising the mandala through meditation, the knots of the veins are unloosened, and light is created.

When people realize that the law of karma is very important, they will also take responsibility for creating better future.

I have tried to unite these powerful symbols in my paintings in order to combine two totally different art styles; the western and the Tibetan. The mandala symbolizes Tibetan art and the roots depict the freedom in contemporary western art. Taken together, the two have opened my mind to a vast unlimited space of creative potential.

When a work of art or any phenomena touches my soul, no matter whether beautiful or ugly, I believe this impression to be art. Naturally, my art is seeking to always express my internal spirit world; the wide and generous Buddhist world is my artistic resource. When starting on a work now, I do not always know how the picture will be. Even when I have clear ideas about image and colour at the beginning, they may change during the creative process. I feel my art has developed from mere depiction of the topic towards a visual discussion of impressions.

Sherab Gyaltsen

Oslo, April, 2010

Acknowledgement and conclusion:

To visit European art galleries and possibly even to study European art techniques and perspectives was the constant dream of my early years. However, numerous attempts to realize the dream over the years all seemed to be of no avail. Since 2006 I had participated in the English classes arranged by the Network for University Co-operation at Tibet University. Here I met my English teacher Ragnhild Schea, who has been helping me to improve my English level; she also consistently encouraged me to apply for a Master degree scholarship. This was the foundation of my study in Norway; so I first would like to express my gratitude her.

My two years study in Norway has near passed. Looking back over this time, there are many people I would like to give my thanks for having made the stay at Khio such an interesting and gratifying time:

From my supervisor Professor Gerd Tinglum, art theory teacher Olga Schmedling, Mr. Ramberg. I have learned many novel things about art which truly have opened new doors in my own creative process, besides they taught me to understand and appreciate western art and art history. I have also visited galleries and art museums in other European countries, as well as having learned about many masterworks from all over the world from ancient times to today from extensive reading. I am proud to say that today I have a fair understanding of contemporary art, which is in particular due to Professor Gerd Tinglum, whose wise guidance in my work helped me to open my perception to new horizons. After these two years, I have now a good command of my intention of blending Tibetan traditional art with contemporary art forms. My deepest thanks to Gerd Tinglum and also to my English teachers in Oslo: Kevin Andrew Firth and Carol Knudsen. Thanks also for the kind support and hospitality of Rinzin Tagyal at the Network office at the university in Oslo.

At last, but most important, my heartfelt gratitude to Tibet University and The Network for University Cooperation Tibet-Norway; without the cooperation between the two I would never have had this experience. And also I deeply thank The Network for University Cooperation Tibet-Norway for the funding of this book.

April, 2010

Reference List:

For general understanding of the Buddhist concepts of the Four Noble Truths, a plethora of literature exists. One example is Trungpa, Chögyam & Lief, Judith, 2009,The Truth of Suffering and the Path of Liberation

Sentences on Conceptual Art, Sol de Witt & Alicia Legg, 1969

Fig. 80: www.littlepaperplanes.com/marlene.jpg

Fig. 95: www.longleaf.net/mandala

Fig. 55: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edvard_Munch

The Story about the Dog Pulling a Horse and a Fox Wearing a Hat: Ro sgrung

(vetala tales). Lhasa: Bod ljongs mi dmangs dpe skrun khang, 2000

(Tales of a Dead Body Speaking. Tibetan Publishing House. Lhasa)