asianart.com | articles

Download the PDF version of this article

by Jane Thurston-Hoskins

Published November, 2020

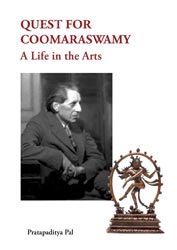

Bayeux Arts, Calgary, Canada, 2020

I have a vivid memory of Thursday afternoon lectures in my first year at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London (SOAS) when we were given a rather general introduction to the discipline of Art History. Early in the course we were instructed to read “The Dance of Shiva” by Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, by way of an introduction to the mind of a great philosopher, seen through his observation of a single form; in particular, we were told to consider how the Natarajah directs and influences ideas and opinions between South Asia and the west. Coomaraswamy, of Sri Lankan and British heritage was uniquely placed to understand and reveal those implications.

I have a vivid memory of Thursday afternoon lectures in my first year at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London (SOAS) when we were given a rather general introduction to the discipline of Art History. Early in the course we were instructed to read “The Dance of Shiva” by Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, by way of an introduction to the mind of a great philosopher, seen through his observation of a single form; in particular, we were told to consider how the Natarajah directs and influences ideas and opinions between South Asia and the west. Coomaraswamy, of Sri Lankan and British heritage was uniquely placed to understand and reveal those implications.

Then, the following Thursday’s lecture focussed on someone else, I forget who, and “The Dance of Shiva” was put back on its library shelf awaiting the next year’s intake of students. How welcome now, to return to the great man through “Quest for Coomaraswamy” by Pratapaditya Pal, and to deepen one’s appreciation of his contribution to the ways in which we see and participate in creative activities in the early 21st century. More than seventy years after his death, it becomes clear that he predicted the direction in which art was moving; he appreciated and encouraged innovation and I suspect he would have been delighted by walls covered with graffiti, by mobile phone selfies and by the manipulation of the visual image that is achievable on a computer. This appreciation is long overdue!

Coomaraswamy

at his desk

Dona Luisa

To be able to write about so many aspects of a remarkable mind is an achievement in itself and Pratapaditya Pal has produced a work that is informative, thought provoking and a pleasure to read. He is uniquely qualified to write on Coomaraswamy. From 1967 to 1969 he held the post of “Keeper” (Curator) of Indian Art at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston (MFA), following in the footsteps of AKC, who had sat at the same desk between 1917 and his death some thirty years later. As Pal informs us in his Introduction, shortly after his own arrival in Boston, he had the pleasure of meeting Dona Luisa Coomaraswamy, AKC’s widow and he subsequently met his son, Rama and others who had known and worked with the savant.

Pal moved from Boston to a distinguished career at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) and under his guidance, the collection of South and Southeast Asian and Himalayan art became one of the finest in the United States. The catalogues of the collection, written by Pal in the 1980’s, form one of the best introductions to the field that any student could wish for. After his retirement from LACMA, he continued his research and writing at the Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena and the Art Institute of Chicago. He has written extensively on the arts of South and Southeast Asia and the Himalayas; when he was editor of Marg he also initiated and oversaw projects involving others. He has further curated numerous path-breaking exhibitions and two stand out for me in particular: “Himalayas” at the Art Institute of Chicago in 2003 was a bountiful event, encompassing the entire region from Kashmir through Tibet and it included some of the finest works in museum and private collections. The second is an earlier and less weighty catalogue of exquisitely mostly Rajput pictures depicting the raga or musical modes, which were collected mostly by AKC for Boston and to which the UK and USA were introduced in the early 20th century by his second wife, Ratan Devi. In 2014, Pratapaditya Pal was honoured by SOAS with the creation of an academic post bearing his name; in November 2020, Dr. Stephen A. Murphy takes up the post of Pratapaditya Pal Senior Lecturer of Curating and Museology.

It is well known that Coomaraswamy, having been given the pioneering role of curator of the Indian collection at the MFA, Boston, increasingly turned his attention to the deeper philosophical underpinnings of the art; Pal has done the opposite, extending his passion for the South Asian, Himalayan and Southeast Asian aesthetic traditions to the widest possible audience by making the subject approachable and enjoyable as well as scholarly.

In the Preface to his latest work Pal modestly states that ‘Not being a professional biographer or a psychologist but a mere art historian, the task proved to be daunting.’ That sentence alone opens the door to the extraordinary mind of Ananda K. Coomaraswamy.

About fifteen years ago, the British biographer, Antonia Fraser, published a highly entertaining work on King Louis XIV of France. Entitled “Love and Louis XIV” it approaches the king though the influence of the numerous women in his life. To some extent, Pal’s biography of Coomaraswamy follows a similar path. The son of a remarkable British woman, AKC married no less than four equally fascinating women who, at different stages of his life, directed his attention through their own attainments into a deeper exploration of his own thoughts. His father, Sir Mutu Coomaraswamy, had less direct influence due to his untimely death when AKC was only a baby. AKC was raised in in the UK by his English mother, Elizabeth Beeby and educated at a public school, but with a deep appreciation of his Sri Lankan Tamil paternal forebears and heritage. As a boy, he visited the island and he would return there at the start of his career, surprisingly perhaps as the first director of the Mineralogical Survey of Ceylon. Nevertheless, one wonders if he would have been Coomaraswamy without his English upbringing and education.

Thereafter, the progress of the scientist revealed his broadly enquiring mind and constant pursuit of knowledge. He began to study and write about South Asian art and architecture, encouraged by his first wife, Ethel. He visited India, befriending members of the Tagore family and Ernest Binfield Havell in Calcutta (now Kolkata). A further enduring influence was that of Swami Vivekananda and his disciple, Sister Nivedita, a remarkable Irish woman who had embraced his beliefs and became an authority on Indian philosophies and culture. The famous Japanese savant Okakura Kakuzo, a friend of Sister Nivedita and the Tagore family, was Coomaraswamy’s predecessor at the Boston Museum and although they never met, was an influence on him, as Dr. Pal discusses.

On their return to England, AKC and Ethel began an association with the followers of William Morris and the Arts and Crafts Movement, filling their home with artworks they had commissioned in Sri Lanka, establishing a printing press and, in Ethel’s case, beginning a distinguished career as a weaver. Inevitably, one sees a connection with the Kiplings, but unlike John Lockwood and Rudyard, Coomaraswamy’s appreciation of Indian traditions became linked to a rejection of his British heritage. His decision to be a conscientious objector in the First World War was driven by his rejection of the principles that continued to justify a colonial presence in India and Sri Lanka. This raised the ire of the British government and his prospects of finding a job in Britain evaporated. Moreover, by 1916, his marriage with Ethel had ended as he found a new love in the famous musician, Alice Richardson (Ratan Devi) whose mastery of both Western and Indian music attracted the attention of music lovers in the UK. She was invited to tour the USA and so the couple sailed across the Atlantic seeking fame and fortune. Undoubtedly Ratan Devi encouraged his interest in both Western and Indian music.

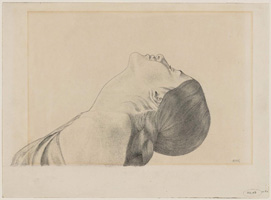

Stella Bloch

Stella Bloch

For a couple of years in America, they performed together to great acclaim, she as the exponent of Indian music half a century or more before Ravi Shankar, and he as the theoriser. They were divorced after she gave him two children. He settled in Boston where the museum acquired his collection through Denman Waldo Ross, to be discussed below. It did not take him long to find a third wife, the dancer Stella Bloch, an emigree from Europe, who developed his understanding of dance as an integral part of South Asian culture. In the west, there has been an increasing tendency to categorise the arts separately, for instance; painting, music, poetry, dance. AKC embraced them all and then went on to show the world how they belong to a single inter-dependent network that is perhaps understood and expressed most readily in Asian, notably Indian culture. Interestingly, his fourth wife, Dona Luisa, was a social photographer and photography and film always fascinated AKC; indeed, he predicted that film would become the dominant form of expression that it now is around the world. Beyond that, he expressed the belief that art should be based on realism for it to succeed. It had to be recognisable in order to be understood and to influence the next generation of creative artists.

As I read Pal’s book and was guided through AKC’s life I was interested in his opinion of the 'true artist". He had little or no time for the picturesque and I wonder if this reflects his aversion to the British Empire and things British. I wonder what he thought of the Daniells? Did his idea of industrial art stem from William Morris’s belief that everything should have beauty, regardless of its purpose? Certainly, during AKC's lifetime many British painters, such as Paul Nash and Eric Ravilious identified the ways in which one can abandon the picturesque and address realism before identifying the aspects of anxiety and beauty within.

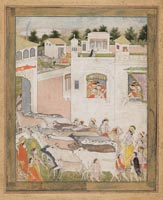

How did all this relate to AKC’s work as curator of Asian Art at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston? Beginning with “The Dance of Shiva”, the philosophical works that he wrote in the congenial atmosphere of the Asian department are his enduring contribution to the wider field of Art History. He became part of an open-minded group of individuals with a sense of responsibility to explore the world through its art. A figure who stands out from the pages of ‘The Quest for Coomaraswamy” is Denman Waldo Ross, who Pal describes as ‘a titanic collector of art, including Indian, and a generous benefactor long before he and Coomaraswamy met.’ The works that Ross acquired and gave to the Museum are testament also to his exquisite taste. Pal gives due credit to this in his illustrations of masterpieces given by him to the MFA that continue to attract visitors. Readers can find an eloquent description of the relationship between Ross and Coomaraswamy in "A Tale of a Collector and Curator: The Ross-Coomaraswamy Bond", an excerpt from the book on asianart.com. During AKC’s long tenure there, the Museum acquired works intended to present as many aspects of India as possible, both its historic culture and future outlook. The collection of Indian paintings is outstanding both from the point of view of academic interest and visual pleasure! However, demonstrating his wider concerns for the future of the MFA, it was AKC who persuaded the Trustees to begin collecting photographs of works of art.

The Hour of Cowdust |

Durga as Mahishasuramardini |

Fertility goddess (yakshi) |

I wonder if someone lacking AKC’s Sri Lankan/English background, could ever have achieved such an understanding of what motivates the creation of art. As I read “The Quest for Coomaraswamy”, I spent some time pondering the western concept and categorisation of "artist" which can so often stifle the desire and ability to create. All too often I remember my art teacher at school telling me that I was "doing it wrong" because my ideas did not comply with hers! In the west we recognise "artists" and we either place them on a pedestal, like a museum exhibit, or we feel we have the right to criticise something we don't understand, instead of making an attempt to do so. I also contemplated the extent to which AKC’s experience of America shaped his work there. A society that lacked the prejudices of the British Empire, even if it harboured some of its own, allowed him to express his appreciation of India and to place it in the context of world culture. As a scientist and writer, AKC knew that we all have to find a means of communication, then he identified art as an effective way of doing so. Vitally when observing, for instance, eastern Indian Buddhist sculptures, he explained how art has a language of its own that, like music, extends beyond the spoken word.

Above all, as “The Quest for Coomaraswamy” by Pratapaditya Pal so amply explains, Coomaraswamy’s work reflects his awesome capacity to move between diverse academic disciplines (and he was master of so many). I am left thinking about his desire to preserve pre-imperial Indian traditions, in the way that Lockwood Kipling, for instance did, while using them to invite investigation into India’s future role in the world. On the surface, that might go beyond the primary role of a museum curator, but it was in the surroundings of the Boston Museum that AKC developed his thoughts and wrote his finest philosophical work. He used art to explore the depths of his mind; I fear my teachers at SOAS hoped to achieve something along those lines with me, but that was too much to hope for in a single lecture.

asianart.com | articles