Teaching the Dharma in Pictures:

Illustrated Mongolian Books of the Ernst Collection in Switzerland

by Karénina Kollmar-Paulenz, University of Berne/Switzerland

(click on the small image for full screen image with captions)

Introduction

The Swiss nobel laureate for chemistry of 1991, Prof. Richard Ernst,[1I owe deep gratitude to Professor Ernst for his kind permission to publish the illustrations and for his constant support of Mongolian Studies in Switzerland. A special thanks goes also to Daniela Heiniger who prepared the photos.] owns what is perhaps the largest private collection of Tibetan and Mongolian xylographs and manuscripts in Europe, consisting of more than 750 Tibetan and more than 150 Mongolian texts. All the texts are of Mongolian origin, dating from the early 17th century to the first half of the 20th century. The collection is now in the process of being catalogued by Dr. Daniel Scheidegger, former research assistant at the Institute for the Science of Religion at Berne University, and the author of this paper. Illustrated manuscripts and xylographs in Mongolian language form part of this unique collection. They[2The collection contains many Tibetan (and some) Mongolian astrological texts with often colourful illustrations. They are not included in this communication.] consist of a couple of the well-known Molon toyin stories, some general hell picture books, an illustrated life of Mi la ras pa and a commentary on the benefits of the Vajracchedikā-Prajñāpāramitā. All of them have been produced in the 19th and early 20th century. These books belong to the literary genre called jiruγ-tu nom, “book with illustrations”, and most of them are handwritten, not printed. Although illustrated books have been known in Mongolia as early as the 17th century,[3Compare György Kara, Books of the Mongolian Nomads. More than Eight Centuries of Writing Mongolian (Bloomington: Research Institute for Inner Asian Studies, 2005), 248-255.] the majority of the jiruγ-tu nom nowadays known appear not earlier than the 19th century. They were used in private households, by wandering monks, the so called badarči, and by itinerant story-tellers who in the course of their narration would point with a stick to the different scenes in the picture book.

In recent years scholars have turned to the study of the “written word [...] as a locus of cultural and social practices,”[4Kurtis R. Schaeffer, The culture of the Book in Tibet (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009), VIII.] exploring culture in a single material and at the same time highly symbolic object, the book. In Buddhist studies research into the cult of the book has been well prepared in the groundbreaking contribution by Gregory Schopen.[5Gregory Schopen, “The Phrase `sa prtivīpradśaś caityabhūto bhavet’ in the Vajracchedikā: Notes on the Cult of the Book in Mahāyāna.” Indo-Iranian Journal 17 (1975): 147-181. There have been a few studies about the book and its social and cultural aspects in Chinese culture, see for example Benjamin Elman, From Philosophy to Philology. Intellectual and Social Aspects of Change in Late Imperial China (Los Angeles: UCLA Asian Pacific Monograph Series, 2001), and Joseph P. McDermott, A Social History of the Chinese Book. Books and Literati Culture in Late Imperial China (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2006). Furthermore Craig Clunas addresses questions of the interplay between material and visual aspects of culture by an examination of texts in Ming China, see his Empire of Great Brightness. Visual and Material Culture of Ming China, 1368-1644 (London: Reaktion Books, 2008), especially chapter 3, 84-111.] Recently, scholars of Mongolian studies have turned to the study of the culture of the book, too.[6Vesna Wallace, “Texts as Deities: Mongols’ Rituals of Worshipping Sūtras and Rituals of Accomplishing Various Goals by Means of Sūtras.” Tibetan Ritual. Edited by José Ignacio Cabezón (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 207-224. The paper has to be read with caution, as there are some obvious mistakes. Concerning the Mongolian cult of the book, see also the remarks by Elisabetta Chiodo, The Mongolian Manuscripts on Birch Bark from Xarbuxyn Balgas in the Collection of the Mongolian Academy of Sciences. Part 2 (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2009), 5-6.] It allows for an analysis of the social, cultural, economic and political areas of Mongolian societies which are interrelated in the material object of the book. But although including ritual and performative practices, this approach still focuses very much on verbal literacy and textual representation, leaving aside visual literacy and visual representation. It thus makes it difficult to include in the analysis the illuminated books so popular in 19th century Mongolia. During that period we notice a kind of “pictorial turn” in Mongolian book production, demonstrating a shift in the representational practices. This shift coincides with a marked deterioration of the living conditions in the outer as well as the inner Mongolian regions during the late Qing dynasty. Mongolian society in the Qing empire was (roughly) divided into two main classes, the nobility and the subjects (albatu)who were liable to render corvée duties. They were divided into imperial subjects under the Manchu administration, and qamjilγa, the personal subjects of the nobility. A third group, the šabi, consisted of the monastic subjects who belonged to the monasteries and the high lamas. Trade was mainly in the hands of Chinese merchants, who took high interest on the nobility who could never pay off their debts. The monasteries worked hand in hand with the Chinese trading firms and themselves often developed into large trading houses. Traditional handicrafts declined because the Mongol craftsmen could not compete with the Russian hardware and the Chinese merchandise which was increasingly imported. By the middle of the 19th century, while wealth was accumulated in a few hands, a substantial part of Mongolian society was impoverished. Cases of starvation quite frequently occurred.[7Charles R. Bawden, The modern history of Mongolia (London and New York: Kegan Paul, 1989), 142-143.] The situation triggered different reactions. Some nomads took to vagrancy beyond the borders of their banners to escape the burden of forced labour for their overlord, others tried to survive by joining marauding bands. In Inner Mongolia, probably first in the Ordos regions, a resistance movement whose members called themselves duγuyilang, “circle”, was built.[8Henry Serruys, “Documents from Ordos on the `Revolutionary Circles’. Part I,” Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 97, No. 4 (1977): 482-486.] In the literature of the time the sayin ere, the “good man”, Robin Hood-like men who allegedly robbed the rich and distributed their booty among the poor, were idealized and soon became a symbol for the resistance against the social oppression. Monks turned their back on their monasteries and became badarči, wandering monks who often sharply criticized the bigoted and morally depraved clergy. New ways of social communication commenced, which made use of the traditional literary forms, but filled them with new contents. In anonymous orally transmitted ballads, songs and animal fables[9In the form of the traditional üge and üliger.] banner regents, nobles and corrupt lamas were satirically portrayed and criticised.[10For example the Qalqa banner official Gendün meyiren (ca. 1820-1882), who was famous for his satirical animal tales, see Walther Heissig, Geschichte der mongolischen Literatur. Bd. II, 20. Jahrhundert bis zum Einfluss neuer Ideen (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1994), 623-627.] These new forms of social representation simultaneously aimed at social criticism and moral advice. The picture-books of the Ernst collection are situated in this socio-cultural context. They were produced in the monasteries, as can be seen from the few colophons which are preserved, but they target the lay population. Despite their different contents, the picture-books in the Ernst collection have one theme in common, the hell descriptions. Be it Molon toyin, Mi la ras pa or one of the heroes in the Sūtra on the benefit of reciting the Vajracchedikā-Prajñāpāramitā, they all find their way into the Buddhist hells. In their concentration on the hells the picture-books draw on a collective imaginaire which their mostly anonymous authors use for didactic goals. In their complex relation between word and picture which requires from the competent reader a constant code switching between “verbal and visual literacy”,[11W.J. Thomas Mitchell, Picture Theory. Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1994), 89.] the jiruγ-tu nom may be described as “imagetexts”,[12Mitchell, W.J. Thomas. Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation. (Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press, 1994), 89, n. 9.] synthetic works combining image and text.

Molon toyin tales

The collection contains four Molon toyin-tales. This well-known tale[13For the transmission history of the story see Matthew Kapstein, “Mulian in the Land of Snows and King Gesar in Hell: A Chinese Tale of Parental Death in Its Tibetan Transformations,” Brian J. Cuevas and Jacqueline I. Stone (eds.), The Buddhist Dead. Practices, Discourses, Representations (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2007), 345-377, especially notes 4 and 5 where the relevant literature is given in detail and commented upon.] goes back to the story of Maudgalyāyana’s journeys to the Buddhist hells and his ignorance of his mother’s places of rebirth as told in the Mahāvastu.[14See J.J. Jones, The Mahāvastu (London: Luzac, 1949), vol. 1, 6-21, for the description of Maudgalyāyana’s hell journeys.] Along the way from India through Central Asia to China these tales were further elaborated and retold in two separate works, the “Sūtra of the Yulan Vessel” (Yulanpen jing)[15Its Tibetan version has been included into three manuscript versions of the bKa’ `gyur under the title `Phags pa yongs su skyobs pa’i snod ces bya ba’i mdo, see Kapstein, “Mulian in the Land of Snows”, 348. Whether the Yulanpen jing is indeed a translation from an Indian original, is still open to discussion.] and the “Transformation text on Mulian Saving his Mother from Hell” (Damuqianlian mingjian jiumu bianwen).[16In the Tibetan documents from Dunhuang (M.A. Stein collection) a short verse version of the story, based on the Damuqianlian mingjian jiumu bianwen, is preserved. Kapstein, “Mulian in the land of Snows”, 351-353, provides a translation of this short text. The Damuqianlian mingjian jiumu bianwen was well known in later Tibetan literature, and Jampa Samten mentions a version of it to be preserved in the manuscript bKa’ `gyur of O rgyan gling, under the title Me’u `gal gyi bu ma dmyal khams nas drangs pa’i mdo, see Jampa Samten, “Notes on the Bka’-`gyur of O-rgyan-gling, the Family Temple of the Sixth Dalai Lama (1683-1706)”, Tibetan Studies: Proceedings of the 6th Seminar of the International Association of Tibetan Studies, Fagernes 1992, Vol. 1, ed. by Per Kvaerne (Oslo: The Institute for Comparative Research in Human Culture, 1994), 395-396.] As Matthew Kapstein has recently shown,[17Kapstein, Matthew. “Mulian in the Land of Snows and King Gesar in Hell: A Chinese Tale of Parental Death in Its Tibetan Transformations.” Brian J. Cuevas and Jacqueline I. Stone (eds.), The Buddhist Dead. Practices, Discourses, Representations. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2007, 346-350.] there is an extensive Tibetan tradition of stories about Me’u gal gyi bu, as Maudgalyāyana is often called in Tibetan manuscripts, going back to the Chinese texts mentioned above, which have been introduced in Tibet during the Tang dynasty via Dunhuang. The Tibetan tales became, as Kapstein has convincingly shown, assimiliated to the `das log genre.[18Kapstein, Matthew. “Mulian in the Land of Snows and King Gesar in Hell: A Chinese Tale of Parental Death in Its Tibetan Transformations.”, 355-358. For a study of the `Das log see Bryan J. Cuevas, Travels in the Netherworld. Buddhist Popular Narratives of Death and the Afterlife in Tibet (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008). See also Francoise Pommaret, “Returning from Hell,” Religions of Tibet in practice. Edited by Donald S. Lopez, Jr., Abridged edition (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2007), 377-388, and Bryan J. Cuevas, “The death and Return of Lady Wangzin: Visions of the Afterlife in Tibetan Buddhist Popular Literature”, Cuevas and Stone (eds.), The Buddhist Dead, 297-325.]

Furthermore, the Damuqianlian mingjian jiumu bianwen belongs, as indicated by the title, to the literary genre of the bianwen, the “transformation texts”, and texts belonging to this genre were closely connected with oral recitation which were accompanied by paintings of the narrated events.[19A new evaluation of the complex relation between bianwen and bianxiang paintings gives Wu Hung, “What is Bianxiang? - On the Relationship Between Bunhuang Art and Dunhuang Literature”, Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, Vol. 52, No. 1 (Jun. 1992), 111-192. I am grateful to Amy Heller who brought this paper to my attention.] Whereas the Chinese Mulian-stories were performed in a picture recitation,we do not have evidence of this kind concerning the Tibetan Me’u gal gyi bu-stories. But the motif of Mulian’s journey to the hells has been included into the Tibetan Gesar-epic, of which the last episode is called the “Dominion of hell” (dmyal gling) and which in many respects resembles the story of Mulian searching in the hells for his mother.[20See Kapstein, “Mulian in the Land of Snows”, 358-362, who argues that the deep impact of the Chinese Mulian legends upon Tibetan narratives of unexpected parental death and their rebirth in the hells can be seen in the Gesar epic. The hero becomes Gesar and not Mulian. The Gesar epic also has a strong tradition of picture recitation, so that the close association of the Mulian stories with the Chinese bianwen surfaces again in the epic performance.] In Mongolia the picture recitation was probably influenced by the Chinese bianwen. Although the text of the Molon toyin-tale was translated from the Tibetan, the Mongolian name of the hero, Molon, points to a direct Chinese influence, as Molon derives from the Chinese Mulian, and not from the Tibetan Me’u gal gyi bu. The Tibetan text, `Phags ‘dus pa chen po byang chub sems dpa’ me’u gal gyi bu’i ma la phan bdag pa’i mdo,[21There also exists a fake Sanskrit title of the work, Āryapatabodhicittamudgalyāyana-

matihrdayasūtra.] has been translated by the famous Siregetü güsi corji at the beginning of the 17th century under the title Qutuγ-tu molon toyin eke-dür-iyen ači qariγuluγsan kemekü sudur orsibai.[22See Walther Heissig, Die Pekinger lamaistischen Blockdrucke in mongolischer Sprache (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1954), No. 15, 23-27, who gives an extensive summary of content. See also Walther Heissig, Mongolische Handschriften, Blockdrucke, Landkarten beschrieben von Walther Heissig unter Mitarbeit von Klaus Sagaster (Wiesbaden: Steiner, 1961), No. 138.] He was probably drawing on earlier translations from the 14th century.[23Walther Heissig, Geschichte der mongolischen Literatur. Bd. I, 19. Jahrhundert bis zum Beginn des 20. Jahrhunderts (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1994), 88.] Siregetü’s translation was printed for the first time in 1686,[24This first printed edition, of which to my knowledge only one copy survived, is not well known. Heissig in his Blockdrucke and Geschichte der mongolischen Literatur, for example, does not mention it. The xylograph is kept in the university library at Hohot, see Bükü ulus-un Mongγol qaγučin-un γarčaγ (Kökeqota, 1979), No. 0926 (1), quoted after Aleksej G. Sazykin, Videnija Buddijskogo Ada. Predislovie, perevod, transliteracija, primechanija i glossarii (St. - Petersburg, 2004), 9, n. 11.] and then again in 1708 at Beijing.[25Sazykin, Videnija, 9-10, notes 14-16, provides an extensive list of the libraries which keep a copy of this 1708 edition. Siregetü güüsi čorji’s translation was also printed in the Aginskoe Datsan in Buryatia in the 19th century, see Sazykin, Videnija, 10, n. 18. There also exist a few manuscripts of this translation.] There exist two other Mongolian translations, one by Altangerel ubashi,[26Laszlo Lőrincz, Molon Toyin’s Journey into the Hell. Altan Gerel’s Translation. 1. Introduction and Transcription. Budapest 1982.] a contemporary of the Tüsiyetü qan Gombodorji of the Qalqa (early 17th century), and one in 500 verses, which originated in the Ordos region.

In the 19th century the tales apparently became so popular that illustrated books started to circulate, most of them told and illustrated by anonymous narrators.[27A selection of illustrations from different Mongolian Molon toyin-manuscripts are included in the monograph by Ch. Zhachina, Molon tojny ėkhin ach khariulsan sudar (Ulaanbaatar 1992), see Sazykin, Videnija, 12, n. 34.. Unfortunately, I did not have access to this work at the time of writing this paper.] One of these texts, however,[28Preserved at the Royal Library at Copenhagen, Ms. Mong. 417, and now available in digitalized form. The booklet has been translated into German by Walther Heissig, see his Mongolische Erzählungen. Helden-, Höllenfahrts- und Schelmengeschichten (Zürich: Manesse, 1986), 169-218.] a manuscript preserved at the Kopenhagen Royal Library contains a colophon and mentions as author one Sayin oyutu dalai (Blo bzang rgya mtsho).[29Heissig, Geschichte der mongolischen Literatur, 90-91.] We know nothing about him. His work draws on the one hand on the Beijing xylograph (the translation of Siregetü güüsi čorji), on the other hand on the Chinese versions of the story.[30Heissig, Geschichte der mongolischen Literatur. I, 91-99, provides detailed information about the literary models of the story as told by Sayin oyutu dalai.] A couple of episodes are not included in the xylograph, but we find them in the Chinese versions: Molon toyin’s activities as a merchant, his journey, the splitting of the household property in three parts after his father’s death, the lies of the mother, her punishment by sudden death, her rebirth in the deepest hell and the appearance of the Buddha in this hell.

None of the illustrated Molon toyin-texts of the Ernst collection contains a colophon and thus their authors are unknown. The stories are adjusted to a Sino-Mongolian environment. Maudgalyāyana has become Labuγ, the son of a Mongolian noble man who is active in trade. During his absence Labuγ’s mother leads a sinful life, ridiculing Buddhist monks and rituals and performing karmically un-wholesome actions like slaughtering animals. When she falls ill and dies, she is immediately transferred to the lowest of the hot hells from where Labuγ who, after having entered monkhood, is renamed Molon toyin, rescues her, so that in the end she is reborn in the Sukhāvatī. The story as told in these picture books touches on the notions of filial piety, as the mother dies in the absence of her son, a recurrent theme in the Chinese Damuqianlian mingjian jiumu bianwen.

Much research has already been done on the Mongolian Molon toyin-tales, among them the works of Sarközi,[31Alice Sarközi, “A Mongolian Picture-Book of Molon Toyin’s Descent into Hell.” Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, Tomus XXX (1976):273-308. Sarközi, 276, n. 16, gives a thorough list of the extant Molon Toyin-tales in libraries around the world.] Heissig and Sazykin,[32Sazykin, Aleksej G. Videnija Buddijskogo Ada. Predislovie, perevod, transliteracija, primechanija i glossarii. St. - Petersburg, 2004., 31-65.] to name but a few.[33See also Kh. Zh. Garmaeva, „Ob illjustrirovannykh mongol’skikh spiskakh sutry o Molon-Tojne.“ Tezisy i doklady mezhdunarodnoj nauchno-teoreticheskoj konferencii “Banzarovskie chtenija - 2”, posvjashchennoj 175-letiju so dnja rozhdenija Dorzhi Banzarova (Ulan-Ude, 1997), 207-211. The author describes one copy of the tale and two illustrated manuscripts preserved in the Mongolian fond of the IMBT SO RAN. The text dates from the 18th century.] The texts of the Ernst collection do not add anything new, as they are variations of the already known popular Molon toyin picture books. Their value rather lies in the fact that they show the extent of the popularity these picture-books enjoyed in 19th century Mongolia. The four texts are the following:

1. Molon toyin-u jiruγ-tu taγuji[!] orosibai. 35 x 22 cm, 23 folios, written on modern Russian paper (the emblem of hammer and sickle in the paper water mark is visible on some folios). No colophon. Collector’s reference number: ET 816.

2. No title. Illustrated Molon toyin-tale. 22.1 x 35.4 cm, 28 folios. The text on Russian paper with the paper water mark fabrika naslednikov Sumkina[34A number on the seal cannot be made out. The factory worked since 1829 in Lajsk in the Volga district.]is in very bad condition, many folios are torn and part of the text is missing. Some of the illustrations are only outlined and not filled with water-colours. No colophon. Collector’s reference number: ET 427.

3. No title. Illustrated Molon toyin-tale. Lined booklet, 27 pages. No colophon. Collector’s reference number: ET 325.[35This text is in such a bad condition that only photos of reduced scale are at my disposal. Therefore I cannot provide the exact measurements of the text.]

4. Title illegible, caused by water damage; on the cover folio only “tuγtu” is legible. 35 x 22.3 cm, 25 folios. Each folio consists of two separate sheets glued together, the paper is of Russian origin. No colophon. Collector’s reference number: ET 820.

Text 1 was written in the first part of the 20th century, as can be seen by the paper's water marks and the paper used. Nevertheless the illustrations, either beneath or above the written text, put the story firmly in a Mongolian cultural context of the 19th century. Molon Qatun is depicted in a dress which was typical for married Qalqa women in the 19th century: Her dress has puffed sleeves, which get tight around her wrists, and her hair is done in the Qalqa “horn” fashion.[36For the 20th century compare also U. Jadamsurėn, BNMA Ulsyn ardyn khuvcas (Ulaanbaatar: Ulsyn khėvlėl, 1967), fig. 27 and 28.] She wears a hat decorated with ribbons which was customary for men and women in 19th century Qalqa Mongolia.[37Compare Jadamsurėn, BNMA Ulsyn ardyn khuvcas, fig. 3-6 and 35-36.] Local officials are depicted wearing hats with a peacock feather, indicating their rank within the Qing petty nobility. The pictures contain many detailed depictions of every-day utensils like mats, tables or cooking pots which provide a glimpse into the life circumstances of 19th century Mongolians. Perhaps the drawings of different weapons most strongly show outside influence: hunters shoot with traditional weapons like the bow-string and arrows, but sometimes one comes across a hunter with a rifle.[38Already in the 1630s rifles were among the favoured trade items in the Russian-Oirat trade relations, see Peter C. Perdue, China Marches West. The Qing Conquest of Central Eurasia. (Cambridge and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005), 98-101. The influx of rifles into Mongolia in the 18th and 19th centuries most probably commenced from the important border town Kiakhta (the Chinese Maimaicheng). For evidence of the existence of rifles in late 17th century Tibet compare Amy Heller, “The Life of Gesar Thangka Series in the Sichuan Provincial Museum: Historical and Art Historical Context”.]

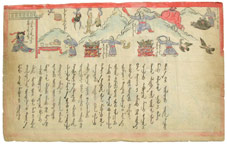

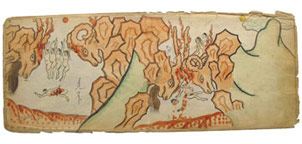

Fig. 1The architecture of the houses and temples in the illustrations of Text 1 and 4 is in Sino-Mongolian style. Other aspects show diverse cultural influences. On folio 7 (Text 1) Molon toyin, still named Labuγ, is depicted sitting in a ger made of grass (ebesün), to his right we see the coffin of Molon qatun, his mother. The coffin has the form of a Chinese wooden box. (Fig 1) In the text beneath the illustration we read that Molon toyin sat in the ger for hundred days and mourned his mother. In the 19th century the funeral in wooden coffins and the mourning custom described here was performed only in regions which had close cultural contact with Chinese culture, like in the eastern regions of Jehol or in the Čaqar regions.[39See Heissig, Geschichte der mongolischen Literatur, I, 89-90.] We cannot, however, be sure about the provenance of this picture book. On the one hand the clothes, the dress and hairstyle of the people point to a Qalqa environment, on the other hand the funeral scene shows strong Chinese influence. Judging by the paper used, the text was composed after the communist take over, in the latter part of the twenties of the 20th century, at the earliest. This opens up different possibilities: The picture books may have been copied over decades without any significant changes and artists may have taken over regionally specific illustrations without adjusting them to a different cultural environment. Furthermore the unknown artists could have had different picture-books at their disposal whose features they combined. This would explain the depiction of Chinese-influenced funeral customs in an obvious Qalqa-environment.

Fig. 2In Text 1 and Text 4 particular attention is given to the depiction of morally appalling behaviour.[40Both texts differ markedly in the quality of the drawings: whereas text 1 is of a very fine artistic quality, the pictures of text 4 are very simple and quite crudely executed. They are very similar in style to Mong. 418, preserved at the Royal Library in Copenhagen.] One scene shows servants of Molon Qatun butchering animals, in another scene Molon Qatun drives away the monks with a long stick (Fig 2).[41The illustrations of text 1 are nearly as explicit as Ms. Mong. 417 (Copenhagen Royal Library).] The accompanying text paints a gruesome picture of her behaviour:

“Molon Qatun: After Labuγ left to do business abroad, she bought with gold and silver many animals, fattened them, hung them up from wooden poles and beat them while they were still alive with wooden clubs so that the blood clotted in their bodies. Saying that they would taste good, she had them killed, mixed the meat and the blood, blended it with garlic and sweet wine, and enjoyed eating it. Furthermore she put fish while still alive into a pot, fried and ate it. Further she put geese, hens and many other birds still alive into a hot pot, so that they pulled out their feathers with their own beaks and died. She dipped the meat of these birds into salt and ate it. Again she pulled out the hearts of pigs still alive, took them and made offerings to the bad Ongγod. She commited various kinds of evil deeds and sins to her heart’s content and enjoyed herself.”[42Molon qatun: labuγ-yi γadaγsi qudalduγalaran odduγsan-u qoyin-a altan mönggü-iyer olan mal-yi qudaldun abcu bortuγun taraγun bolγaju modun-aca elgüjü amidu-bar mun-a-bar jangciju cisü nöji-i beyengdür quriyan amta-ni sayiqan kemeged alaγulun miq-a cisü-yi nayiraγulan sarimsuγ ba: darasu qoliju iden jirγabai: basa jiγasu-i amidu-bar quu toγun-iyar qabaqaγlaju qaγurcu idebei: basa γalaγu takiy-a terigüten olan šibaγu-ud-i amidu-bar qalaγun toγun-du qabqaγlan öberün qošiγu-iyar üsü jolγaγaju ükümüi: tedeger sibaγun-u miq-a-yi dabusun-dur dürejü idemüi: basa γaqai-yi amidu-bar jirüke-yi suγulaju abuγad maγu ongγod-i takin eldeb jüil jüil-ün olan maγu kilingce nigül-i ali dur-a-bar üiledcü jirγan saγubai: The text is identical with Mong. 417 in the Royal Library at Copenhagen, see the German translation by Heissig. Mongolische Erzählungen, 174-175; it is also very similar to the version published by Č. Damdinsürüng, Mongγol uran jokiyal-un degeji jaγun bilig orosibai (Ulaanbaatar: Öbör mongγol-un arad-un keblel-ün quriy-a, 1959), 261-277. A translation of the text published by Damdinsürüng provides Sarközi, “Mongolian Picture Book”.]

The hell scenes make up the better part of the Molon toyin-picture books. They resemble each other quite closely and are already known from other published sources.[43For example in Mong. 417 of the Copenhagen Royal Library or from the picture book Alice Sarközi published, see her “Mongolian Picture Book”.]

The benefit of reciting the Vajracchedikā-Prajñāpāramitā

The Ernst collection holds an illustrated commentary about the benefits of reciting the Vajracchedikā-Prajñāpāramitā. Texts explaining the benefits of reciting the Vajracchedikā have been very popular in Tibet and Mongolia. There exists an early Mongolian translation of this apocryphical collection of tales,[44Tibetan title: `Phags pa shes rab kyi pha rol tu phyin pa rdo rje gcod pa’i phan yod bshad pa’i mdo. ] prepared by Dzhin Čordzhi and dating from the 17th century, entitled Gčodba-yin tayilburi.[45Manuscript of the Palace library in Beijing, as microfilm preserved in the collection of Raghu Vira at New Delhi.] The original translation from the Tibetan consists of 15 stories respectively chapters, and most of the copies preserved in libraries around the world have 15 chapters. Recently, one chapter from the Tibetan version, the tale about the boy who wrote the Vajracchedikā in the sky, has been translated by Kurtis Schaeffer.[46Schaeffer, Culture of the Book, 147.]The Mongolian version of the book has been translated by Sazykin.[47Sazykin, Videnija, 67-108, Latin transcription of the text on pages 109-146. For a Latin transcription and translation of a redaction of this text, published in 1871 in Burjatia, see D. Jondon/A.G. Sazykin, “Mongol’skaja versija rasskazov o pol’ze “Almaznoj sutry.” Mongolica IV, 90-letiju so dnja rozhdenija C. Damdinsurena posvjashchaetsja, SPB (1998): 36-47. An Oirat version of the text is published by Aleksej G. Sazykin, “Ojratskaya versiya rasskazov o pol’ze “Vadzhrachchkhediki””. Peterburgskoe vostokovedenie. Vyp. 10 (1997): 139-160.] Apart from the text with 15 chapters, there exists a version with 22 chapters, as in our case. This version is a unique Mongolian addition and was probably prepared in the second part of the 19th century.[48See Sazykin, Videnija, 18. See also A.G. Sazykin, “Mongol’skie versii rasskazov o pol’ze “Vadzhrachchkhediki””.Pis’mennye pamjatniki i problemy istorii kul’tury narodov Vostoka. Moskva, 1986, Vol. XX, part 1: 70-74.] It contains six new tales, whereas the seventh has come about through the splitting up of the fifth chapter into two parts.[49Sazykin, Videnija, 18.] A Tibetan translation of this longer version was prepared by the Qalqa Qambo Lama Jamyan Garbo (1861-1917). The text can therefore serve as an example of the two-way cultural transmission between Tibet and the Mongolian regions.

The title of the manuscript in the Ernst Collection is given in both Mongolian and Tibetan: Qutuγ-tu bilig-ün činadu kijaγar-a kürügsen vačir-iyar oγtaluγči-yin ači tusa üjegüllügsen sudur-un jiruγ orosiba; Tibetan title in dbu med script: `Phags pa shes rab kyi pha rol tu phyin pa rdo rje gcod pa zhes bya ba theg pa chen po’i mdo’i phan yon kyi ri mo `zhugs so. The manuscript consists of 71 pages in square format (21.5 x 17 cm). Only the title is bilingual, the text itself is in Mongolian.[50Collector’s reference number: ET 365.]

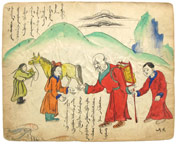

Fig. 3This book is divided into 22 chapters in which the benefits of reciting the Vajracchedikā-Prajñāpāramitā-Sūtra during one’s life time are stressed by giving examples taken from everyday life. The illustrations are lovingly drawn with an evident eye for detail in depicting everyday life. To give just one example: In chapter 19 a boy who is the only son of a wealthy official is bitten by a rabid dog. Although his father immediately takes him to a doctor , the doctor can’t help him. On their way back they meet an old man, obviously a badarči by his appearance, who by reciting the Vajracchedikā-Prajñāpāramitā-Sūtra and blessing him with the book heals the boy, consequently , “although other people died, this boy did not become infected by rabies.”[51Page 59.] On page 58 the old man wears a yandaγ, [52Heissig, Geschichte der mongolischen Literatur, II, 743-744, gives a detailed description of the badarči and his appearance.] a wooden rack, on his back in which he carries his belongings. (Fig 3) In the illustration on page 59 the yandaγ, the typical outfit of a badarči, is seen to his right. (Fig 4)

Fig. 4According to the colophon the text was written and illustrated by the monk Čültrim Sodba of the Ganden Monastery.[53Which “Ganden” monastery, is not specified, perhaps the Ganden Thegchenling monastery in Urga.] No date is given in the colophon. The book was probably written at the end of the 19th, beginning of the 20th century.

To my knowledge, the copies extant in libraries are not illustrated.[54For a thorough documentation of the libraries where copies of the text are kept see Sazykin, Videnija, 16ff. , especially n. 62, p. 18.] At least the catalogues do not mention any illustrations, and also the titles[55The titles of the copies kept in the State Library of Ulaanbaatar are meticulously listed in Sazykin, Videnija, 18, n. 62.] do not contain the generic term jiruγ-tu nom. The copy of the Ernst collection is unique in so far as it does not present the text of the Sūtra, but gives just a very short summary of the story beneath each picture. If one does not know the detailed version, the text often remains obscure. The few lines accompanying the pictures serve to trigger the memory of the storyteller who narrates the tales in an oral performance. The pictures, which translate the tales into a Tibeto-Mongolian social context, are dominant, they convey the message, not the written text.

Hell descriptions

The Ernst collection aptly demonstrates the Mongolian obsession with hell. Apart from the Molon toyin tales and the Vajracchedikā-Commentary which all include hell illustrations, the collection contains three illustrated xylographs, books of illustrations to the canonical Dran pa nyer bzhag.[56The well known Dran pa nye bar bzhag pa’i mdo, Skt. Ārya-saddharmānusmrtyupasthāna, Tib. `Phags pa dam pa’i chos dran pa nye bar bzhag pa, Mong. Qutuγ-tu degedü-yin nom-i duradqui oyir-a aγulqui. See Louis Ligeti, Catalogue du Mongol Kanjur Imprimé (Budapest: Societé Kőrősi, 1942), Nos. 1044-1047.] The author is one Tshe spel dbang phyug rdo rje, his Mongolian name being Erdeni bisireltü mergen bandida gambo. The text has been described in detail by Sarközi and Bethlenfalvy.[57Alice Sarközi, Geza Bethlenfalvy, “Representation of Buddhist Hells in a Tibeto-Mongol Illustrated Blockprint.” Altaica Collecta. Berichte und Vorträge der XVII. Permanent International Altaistic Conference 3. - 8. Juni 1974 in Bonn/ Bad Honnef. Herausgegeben von Walther Heissig (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1976), 93 -136, and Geza Bethlenfalvy & Alice Sarközi, A Tibeto-Mongolian Picture-Book of Hell. Budapest 2010. The last mentioned volume contains a facsimile reproduction of the text as well as a detailed description.]

Fig. 5All three xylographs of the Ernst collection are incomplete, as are all the other known copies so far. They are printed from the same wooden blocks.[58Collector’s reference numbers: ET 405, ET 369 and ET 469.] The illustrations show a Mongolian setting, as can be seen in the depiction of the “sinful passions”: Tiny ger are nestling against a mountain, and the people wear Mongolian dress.[59This illustration is copied in Kara, Books of the Mongolian Nomads, Plate XXXV.] The drawings of the animals and the depiction of the hell beings are very similar to the drawings of the illustrated Molon toyin books.

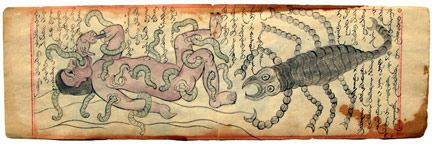

The collection also contains an incomplete illustrated book about the hells, entitled Eldeb jüil-ün yeke tam [!] nuγud orsibai (size 34.5 x 10.8 cm).[60I did not find evidence of a text with this title in other libraries.] It consists of 13 folios without numbering. On each side of a folio is a coloured drawing of one hell. The drawings are beautifully executed in muted colours. They make out the middle of the folio, the text is written around them. (Fig 5) Like in the Sūtra about the benefits of reciting the Vajracchedikā-Prajñāpāramitā, text and picture build a unity.

Fig. 6The last picture book I will briefly introduce is an illustrated manuscript of 117 folios which tells the life of Mi la ras pa (yogacaris-un erketü milarayiba), the cotton-clad saint (1012-1097).[61Collector’s reference number: ET 771. ] The biography of Mi la ras pa, rNal `byor gyi dbang phyug chen po rje btsun mi la ras pa’i rnam thar,[62An overview of the Tibetan biographical tradition concerning Mi la ras pa gives Francis V. Tiso, “The Biographical Tradition of Milarepa: Orality, Literacy and Iconography,” The Tibet Journal XXI, no. 2 (1996):10-21.] composed by gTsang smyon Heruka (1452-1507)[63On him see Gene Smith, “The Life of Gtsang smyon Heruka”. Among Tibetan Texts. History and Literature of the Himalayan Plateau. E. Gene Smith. Edited by Kurtis R. Schaeffer with a foreword by Jeffrey Hopkins (Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2001), 59-79.] in 1488, is among the non-canonical texts translated into Mongolian at an early date.[64Heissig, Blockdrucke, No. 131. Copies of the text are kept in different libraries around the world, compare for example Heissig, Mongolische Handschriften, No. 490, and György Kara, The Mongol and Manchu Manuscripts and Blockprints in the Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (Budapest, 2000), Nos. 141 and 212.] The stories about Mi la ras pa and his songs were widespread and apparently very popular in early 17th century Mongolia, as the newly discovered song fragments from Xarbuxyn Balgas to the west of Ulaanbaatar demonstrate.[65Elisabetta Chiodo, Mongolian Manuscripts, 15-55.] In 1618 the famous translator Siregetü Güüsi corji[66On him see György Kara, “Zur Liste der mongolischen Übersetzungen von Siregetü güüsi,” Documenta Barbarorum. Festschrift für Walther Heissig zum 70. Geburtstag. Herausgegeben von Klaus Sagaster und Michael Weiers (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1983), 210-217, and Čoyiji, “Randbemerkungen über Siregetü güüsi čorji von Kökeqota,” Zentralasiatische Studien 21 (1988-1989): 140-151.] translated the biography into Mongolian.[67For an edition of the text see James Evert Bosson, Yogazaris-un erketü degedü getülgegči milarasba-yin rnam tar: nirvana kiged qamuγ-i ayiladuγči mör-i üjegülügsen kemegdekü orosiba. The Biography of Milaraspa in its Mongolian Version by Siregetü güüsi corjiva. With an introduction by J.E.B. (Taipei, 1967).] This translation was widely known, and in 1756 a revised version of Siregetü güsi corji’s translation was put into print on the order of the second lCang skya Qutuγtu Rol pa’i rdo rje. Another, independent translation was prepared by Toyin čoγ-tu guisi,[68 On him see Walther Heissig, “Toyin guosi ~ guisi alias Čoγtu guisi: Versuch einer Identifizierung,” Zentralasiatische Studien 9 (1975): 361-446.] who was a contemporary of Siregetü güüsi čorji. This translation circulated as manuscript.[69Lázló Lőrincz, Milaraspa Életrajza. Mi-la-pas-pa’i rnam-thar Čoγ-tu guisi fordititása (Budapest, 1967); see also Kara, Mongol and Manchu Manuscripts, No. 318.]

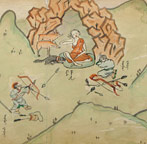

Fig. 7The manuscript in the Ernst collection does not have a cover title, but the first line of fol. 1 starts with “mila boγda-yin ijaγur anu”, “the origin of the saint Mila”. Every second folio consists of an illustration, with the verso side blank. The text is written on Russian paper, with the paper- mill's water mark visible: “fabriki naslednikov Sumkina, No. 6”.[70For Russian paper- mill marks see Zoya Uchastkina, A History of Russian hand paper-mills and their watermarks (Hilversum, 1962).] The scribe’s name is not mentioned, but the date, a female wood-hare-year that is most probably 1915. If the “reader” picks out only the illustrated folios (and ignores the folios of written text in between), this book can easily be “read” as a picture book devoid of text. As the life of Mi la ras pa is transferred to a Mongolian environment, the meaning of the pictures is comprehensible for everybody. Many of the lively scenes deal with hunting episodes, among them the famous meeting with the hunter Gombo dorji (Fig 6). A couple of illustrations are again devoted to hell descriptions. (Fig 7)

Painting technique

The technique of the illustrated books described here is always the same: First, single-colour lines are drawn, either by brush and black ink or by pencil. They serve as a draft-outline for water-colours, as can by seen in the xylographs and manuscripts where colouring of the drawings was started but on many folios has not been completed.[71For example in the blockprinted hell descriptions, or in one of the Molon toyin-picture books (ET 427).] Multi-layered modes of representation are evident in the depiction of nature, in the trees and mountains, and the architecture of houses and temples. Nepalese and Tibetan painting styles, the latter having absorbed Chinese influences, were reintroduced[72During Qubilai’s reign the Nepalese artist Aniga (A-ni-ko) (1244-1306?) was active at the Yuan court. During one of his brief visits to Tibet, `Phags pa Lama met the Nepalese artist and, despite his protestations, brought him to China, where he worked for the Mongols. In 1273, he was promoted head of the Directorate General for the Management of Artisans in the Yuan administration, see Morris Rossabi, Khubilai Khan. His Life and Times (Berkeley/ Los Ageles/ London: University of California Press, 1988), 171. Compare also Christopher Atwood, Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire (New York: Facts on File, 2004), 13-14. Aniga’s Nepalese style was influential during the Yuan and Ming dynasties, and even exerted considerable influence on the famous Mongolian sculptor (and 1st Jebtsundampa Khutukhtu) Janabazar in the 17th century.] into the Mongolian regions during the late 16th century under the Altan Qaγan of the Tumed-Mongols,[73See his Mongolian biography, the Erdeni tunumal neretü sudur, fol. 36r17-18, composed around 1607 by an unknown author.] and continued to spread in Mongolia and Northern China in the 17th century. At the same time, the Manchus introduced Chinese art and architecture to the Mongols.[74See Patricia Berger, Empire of Emptiness. Buddhist Art and Political Authority in Qing China (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2003), 31-33.]

The illustrations in the Jiruγ-tu nom are nearly always executed in water-colours. Some are executed in coloured crayons. These colours have most probably recently been added, probably to increase their market value.

Conclusion

The appearance of picture books in 19th century Mongolia goes along with marked socio-cultural changes in these outer regions of the Qing Empire where social conditions were rapidly deteriorating.[75Perdue, China Marches West, 547-565, gives a lucid analysis of the reasons why the Qing empire declined in the 19th century, laying emphasis on four entangled processes, of which two apply to the situation in the Mongolian lands: the unstable power balance with Mongolian local leaders and the impact of commercialisation on social solidarity.] Two forms of communication, produced by the social realities that shaped the lives of the people, became increasingly important: oral and pictorial communication. Social grievances were expressed on the one hand in orally transmitted ballads, songs, satirical sayings and so on, on the other hand in the imagetexts, a form of communication which operated in a system of signification within the community of image-users. The picture books were used as a didactic means to emphasize Buddhist ethics and moral behaviour, contrasting socio-religious norms to bleak social reality. Social criticism was expressed in Buddhist terms. Social agency, which was mediated in the picture books, shifted away from the monastic establishments and banner offices towards the common people. Normative religious textuality gave way to more secular, visual forms of expression. By drawing on Chinese as well as Tibetan practices of picture recitations the Mongols adapted, modified and transformed these alien cultural aspects into a genuine Mongolian cultural device. In the imagetexts the Mongols negotiated practices, ideas, institutions and values constitutive for their social reality.