asianart.com | articles

Download the PDF version of this article

by Ulrich von Schroeder

Text & images © Ulrich von Schroeder

March 18, 2024

The stūpa in its earliest form was of pre-Buddhist origin and represented a burial mound built over the corporeal relics of significant personalities. Its use was not restricted to any particular religious tradition. After “the passing away into final mahāparinirvāṇa” of the historical Buddha Śākyamuni at Kuśīnagara (Kasia, Uttar Pradesh, N. India), his corpse was cremated with royal honors. The remains were divided among eight kings and eight stūpas were erected in their kingdoms to enshrine Śākyamuni’s corporal relics. The mostly large monuments that contain relics are called Stūpas, whereas those exemplars without relics and usually of smaller size are called Caityas.

Fig. 1. Votive Stūpas at Bodhgayā in India worshipped by Hindus as Śiva-liṅga. The practice of worshipping caityas as Śiva-liṅgas is documented at Bodhgayā in the late 19th century as recorded by Brian H. Hodgson: “In Buddh Gayah there is a temple of Maha Buddha in the interior of which is enshrined the image of Sakya Sinha. At a little distance to the north of the great Maha Buddha temple are many small Chaityas, which the Brahmans call Siva Lingas, and as such worship them, having broken off the Chura Mani from each”.[1] (Photo: After Buddha-Weekly). |

While discussing the assumed purge of Licchavi caityas at the hand of Brahmans with the purpose to render them into Śiva-liṅgas, it is necessary to explain in a few words the origin of liṅgas and their ritual functions. Numerous phallus-shaped objects discovered in the Indus Valley have been interpreted as the cult-objects of indigenous people who were culturally different from the early Vedic Indo-Aryans who objected to such customs. There can be no doubt that phallicism was conceived as a symbol of the potent force at the root of creation. The Post-Vedic Indo- Aryans only openly acknowledged phallicism when it became indivisibly connected with the worship of Rudra-Śiva. The most popular abstract form (niṣkala) of Śiva is embodied by the phallus-shaped liṅga. A mānuṣaliṅga (“man-made liṅga”) has three parts: namely the brahmābhaga – the lowest part of the liṅga that is square; viṣṇubhaga – the middle section of octagonal shape, facing the four cardinal and four intermediate directions; and the rudrabhaga – the topmost part of the central shaft with a rounded tip. The square section at the bottom stands for Brahmā or the aspect of creation. The middle octagonal section represents Viṣṇu or the aspect of preservation. The round shaft at the top represents the aspect of the limitless Maheśvara, the “great lord” (Fig. 2). Liṅgas are customarily mounted upright, at first in a square, later in a round grooved pedestal called jalaharī “small pit of water” with a spout to drain the oblations that serves as bathing-seat (snānapiṭha). In the Śaiva context, the pedestal, serving a utilitarian purpose, came to be identified as the female sexual organ (yoni).[2] The positioning of the liṅga and the yoni are paradoxical phenomena because the liṅga emerges from the yoni, it does not penetrate it. Stone-carved liṅgas can be found in different environments, either as principal icons placed in the sanctum of temples, placed inside small shrines, or in the open.[3] As outlined elsewhere in this essay, Licchavi votive caityas without spire and empty niches removed from their pedestals are worshiped by the Hindus as Śiva-liṅgas.

Fig. 2. Śiva-Liṅga. Stone. Size (?). Nepal (Licchavi Period); circa 5th century. Liṅga, with square, octagonal and round segments decorated with engraved lines (brahmāsūtra). Erected inside a circular grooved jalaharī “small pit of water” regarded as yoni. East side of Gaurī Ghāṭ. Paśupatinātha. Deopatan. Kathmandu. (Photo: Lain S. Bangdel, 1984).[4] |

Sadāśivamūrti or “representation of the everlasting-Śiva” can be represented in the form of a liṅga (phallus) with four faces (caturmukhaliṅga). Each face depicts a different aspect, and additionally two arms protrude from the shaft of the liṅga below each face. All different aspects are identical regarding the hand-held attributes, the rosary (akṣamālā) held in the right hands and the water-flask (kamaṇḍalu) held in the right hands. Thus, only the differences in hairdo, crowns and earrings enable a distinction between the various aspects. In Nepal where the Pāśupatas are the dominant Śaiva sect, the iconography of the four faces was at times interpreted differently. One of the faces sometimes encountered among early Nepalese caturmukhaliṅgas represents Lakulīśa the “lord with the club”, a reformer of the Pāśupata cult who was active in about the 2nd century. Faces of Lakulīśa are distinguished by curly hair like Buddha images and they are visible on several of Śiva-liṅgas.[5] The two illustrated caturmukhaliṅgas have two counter-positioned heads with curly hair and date from the Licchavi period, or 6th/7th century. One of them certainly represents Lakulīśa and the other possibly Buddha, as a syncretistic representation of Śiva and Buddha (Figs. 3–4).[6] The principal reason for the purge of Licchavi caityas must have been their resemblance with Śiva-liṅgas.

|

|

|

Fig. 3. Caturmukha Śiva-Liṅga. Stone. Height: 41.3 cm. Nepal (Licchavi Period); 6th/7th century. Śiva in the form of a liṅga with four faces (caturmukhaliṅga). On all four sides the right hand holds a rosary (akṣamālā), the left hand a water-flask (kamaṇḍalu). Note the two heads with curly hair looking side wards. The one on the left likely represents Lakulīśa and the head on the right possibly Buddha. Faces of Lakulīśa are distinguished by curly hair like Buddha images. This is an example that the four faces not necessarily have to represent Tatpuruṣa (east), Aghora (south), Sadyojāta (west), and Vāmadeva (north) as is often the case. [Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Accession Number: M.88.226) (Acquired in 1988)]. (Photo: Courtesy of LACMA). [7] Fig. 4. Caturmukha Śiva-Liṅga. Stone. Height: 65 cm. Nepal (Licchavi Period); 7th/8th century. The central face and the face towards the opposite direction are depicted with curly hair [not visible on the available photographs]. One of the two faces likely represents Lakulīśa and the other one possibly Buddha. Pāñcadevala Cok. Rājarājeśvarī Ghāṭ. Paśupatinātha. Deopatan. Kathmandu. (Photo: Ulrich von Schroeder, 1965)[8] |

Although almost all surviving Licchavi votive caityas bear empty niches, there are a few caityas that are decorated with images. Certainly, the most famous of them is the Caturvyūha Caitya unearthed in 1956/1957 at the Dhvākā Bāhā in Kathmandu (Fig. 5). The excellent condition is thanks to the fact that this caitya was buried for protection at the time of the purge and remained underground almost a thousand years. Unaware of this, other scholars use the Dhvākā Bāhā Caturvyūha Caitya as an example that there was never a purge, otherwise this caitya would not have survived with the images intact. It is likely that other Licchavi caityas were also buried at the time of the purge awaiting to be rediscovered in future. On Svayambhu Hill in Kathmandu is a Caturvyūha Caitya also from circa 7th century that was not hidden during the purge. All what is left from two pairs of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas decorating originally the shaft are empty niches (Fig. 16). The same fate befell the Caturvyūha Caitya moved from an unknown Buddhist to the Hindu Nandikeśvara Bahāl Ḍhuṅgedhārā at Naxāl in Kathmandu (Fig. 17).

Fig. 5. Caturvyūha Caitya dating from circa 7th century. The shaft is decorated with a pair of Buddhas and a pair of Bodhisattvas standing in niches. The four images are facing the cardinal directions and are surmounted by a caitya with four niches containing identical images of Amitābha in meditation attitude. This well preserved Licchavi Period Caitya, presumably hidden during the purge of caityas, was rediscovered while cleaning the Ikā Pukhu sometime in 1956/1957 on the day of Sithinakhah, on which every well, pond and Hiti in Kathmandu were cleaned until the 1970’s. Dhvākā Bāhā Monastery in Kathmandu. [Personal communication by Sukra Sagar Shrestha]. (Photo: Ulrich von Schroeder, 1976).[9] |

|

|

|

Fig. 6. Votive caitya with intact images but destroyed spire. Licchavi Period, circa 9th/10th century. Stone. Height: 50 cm. Only few Licchavi caityas have survived the Śaiva purge intact. Most likely this caitya and others were buried for safe-guarding. Other Licchavi caityas that were buried might be discovered in future. Musum Bāhā [skt. Maṇi Saṅgha Mahāvihāra]. Musum Bāhā Ṭole. Bare Nani. Kathmandu. (Photo: Ulrich von Schroeder 1976). Fig. 7. The empty niches of this Licchavi caitya were later filled with stone images. Licchavi Period, circa 9th/10th century. Stone. Height: 70 cm. Near Kuṭu Bahī. Cābahil Ṭole. Deopatan. Kathmandu. (Photo: Ulrich von Schroeder 1976). |

Fig. 8. Many Licchavi caityas affected by the purge were moved from their original locations. This stepping stone was perhaps earlier part of the pedestal of a Licchavi caitya. The panel is decorated with a squatting yakṣa holding lotus flowers embedded in foliate scroll motifs (patralāta) with two squatting lions to occupy the corners. Entrance of the principal shrine of the Kuṭu Bahī Monastery in Cābahil. Size: 27 x 128 cm. Licchavi Period, circa 9th/10th century. (Photo: Sunil Dongol, 30 July 2011).[10] |

Thousands of Buddhists caityas carved in stone have been erected all over the Kathmandu Valley, with the earliest dating back to the Licchavi period (circa 400–879 AD). Whereas all caityas set up later than the Licchavi period are decorated with images of Buddhas or Bodhisattvas, most of the surviving Licchavi period caityas have empty niches. There has been much speculation and disagreement regarding the empty niches of Licchavi caityas. Some scholars maintain that the empty niches are part of the original features, others claim that the empty niches are the result of forcibly removed images. Everybody can agree that it serves no purpose to erect caityas with permanently empty niches. It is therefore reasonable to assume, that if the empty niches were made purposely at the time of making caityas, they were intended to be filled with four Tathāgatas, namely Amitābha (west), Amoghasiddhi (north), Akṣobhya (east), and Ratnasambhava (south). However, as there never existed any restriction in Buddhism regarding the presence of images, why would the artists make empty niches instead of carving the images into the caitya? The Buddha images of the large Licchavi Period caityas were permanently installed, as documented by the Mahācaitya on Svayambhū Hill, Dharmadeva Caitya (Cārumatī Stūpa) at Cābahil; Kāṭheśimbhū in Kathmandu. Why would it be different for the smaller votive caityas. As will be detailed later, there is ample evidence to prove that the images were forcefully removed from Licchavi Period caityas with the intention to alter them within acceptable limits for the Hindus to be worshipped as liṅgas (Fig. 23). Caityas with empty niches are in most cases considered by Buddhists to be desecrated and not any longer objects of worship. As an object of worship, a caitya needs to be placed upon a pedestal, is ornamented mostly with Buddha images, and a dome topped by a spire. This explains why only few of the Licchavi Period votive caityas with empty niches are still installed at their original setting within Buddhist monasteries. Fragments of different Licchavi Period caityas are sometimes assembled, or added as fragments to caityas made during the Malla Periods. In some cases, the missing spires were reinstalled and empty niches filled with separately carved Buddha stone images as a permanent installation (Figs. 7 & 15). Now, what would be the purpose of making caityas with empty niches to be filled then permanently with separately carved stone images?

Fig. 9. Licchavi Stūpa with empty niches at the older Teku cremation ground. Kathmandu. (Photo: Sukra Sagar Shrestha, 1997). |

|

|

|

Fig. 10. Licchavi caitya with empty niches located near the Dharmadeva Caitya (Cārumatī Stūpa). Cābahil. Deopatan (Kathmandu). [Established by King Dharmadeva about middle of 5th century]. (Photo: Ulrich von Schroeder, 15 April 2023). Fig. 11. Licchavi caitya with empty niches located near the Dharmadeva Caitya (Cārumatī Stūpa). Cābahil. Deopatan (Kathmandu). (Photo: Ulrich von Schroeder, 15 April 2023). |

|

|

|

Fig. 12. Licchavi caitya with empty niches located near the Dharmadeva Caitya (Cārumatī Stūpa). Cābahil. Deopatan (Kathmandu). [Established by King Dharmadeva about middle of 5th century]. (Photo: Ulrich von Schroeder, 15 April 2023). Fig. 13. Licchavi caitya with empty niches located at Misā Hiti or “woman’s fountain”, because only woman could bath here before. Outside the main gate to the Kumbheśvara Śaiva temple compound. Konti Ṭole. Patan (Kathmandu Valley). (Photo: Ulrich von Schroeder, 20 June 2012). |

|

|

|

Fig. 14. Licchavi caitya with twelve empty niches in 1976. Located in the Sī Bahī Stūpa compound. Naxāl. Kathmandu. (Photo: Ulrich von Schroeder, 1976). Fig. 15. The same caitya in 2011 with the formerly empty niches filled with separately carved stone images as a permanent installation. Sī Bahī Stūpa compound. Naxāl. Kathmandu. (Photo: Ulrich von Schroeder, 13th August 2011). |

There is strong evidence that sometimes in the past a purge directed against Licchavi caityas happened during which their sculptural decoration was replaced with empty niches. Its existence is manifest through the almost three hundred of desecrated Licchavi caityas dispersed all over the Kathmandu Valley. The exact date and length of this purge remains unknown, but all affected caityas pre-date the Malla Period (circa 1200–1769). That means that the purge started possibly sometimes in the 9th century during the late Licchavi Period and ended during the Transitional Period (circa 879–1200). The principal reason for the purge of Licchavi caityas was their resemblance with Śiva-liṅgas. The shafts of stone liṅgas consist of square, octagonal, and round sections, thus very similar to an altered stone caitya of which the images and the spire have been chiseled away. Unaltered caityas decorated with Buddha images were perceived by Śaiva fanatics as desecrated liṅgas equaling blasphemy. By replacing the images with empty niches and removal of the spires, caityas started resembling liṅgas (Figs. 10–14). Among Newar Buddhists, the notion is prevalent that there was an awful persecution of Buddhists by the seventh reincarnation of the renowned Indian Śaṅkarācārya in Nepal in the 9th century (though this date has been disputed).[11] Śrī Ādi Śaṅkarācārya is considered an incarnation of Śiva and the world’s greatest Guru (Jagathguru). He purified Vedic knowledge by teaching discernment and he instituted the worship of deities as worshipping different forms of the one God. The Nepalese Buddhists believe that one of the incarnations of Śaṅkarācārya is responsible for the purge which resulted in empty niches of all caityas which were not hidden during that time. The caityas were re-shaped in response to the most common of Śaiva emblems, the liṅga raised in the yoni. The Tathagatas on the four sides correspond to the four faces the Śaiva emblem so frequently shows in its caturmukhaliṅga form. Once images and the spire were removed from a caitya its dome became very similar to a Śiva-liṅga. Caityas and liṅgas not only share visual aspects in their manifestations, but are also related to each other during some religious events. A particular Buddhist procession to eight liṅgas located in the Kathmandu Valley is completed with a visit to four caityas.[12]

|

|

|

Fig. 16. On Svayambhū Hill is a Caturvyūha Caitya also from circa 7th century that was not buried. Unprotected the caitya became a victim of the Śaiva purge as indicated by the empty niches. (Photo: Vajra Alsop, 30 July 2022). Fig. 17. Inside the Nandikeśvara Bahāl Ḍhuṅgedhārā at Naxāl in Kathmandu is another Caturvyūha Caitya also from circa 7th century that became also a victim of the Śaiva purge. Without spire and placed inside a grooved pedestal (jalaharī) there can be no doubt that the former caitya is now worshipped as a Śiva-liṅga. (Photo: Ulrich von Schroeder, 13 August 2011). |

|

|

|

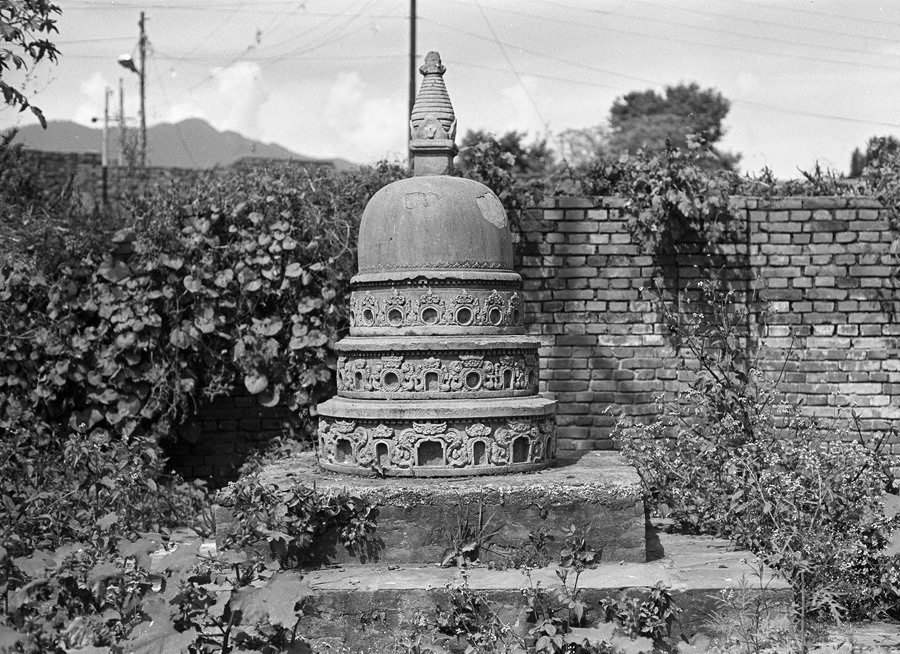

Fig. 18. Licchavi caitya with the empty niches filled with separately carved stone images of Buddhas that are partly damaged. Outside the Svatha Nārāyaṇa Hindu Tempel. Svatha. Patan. Patan. (Photo: Ulrich von Schroeder, 15 April 2023). Fig. 19. This Licchavi caitya manufactured without images bear a strong resemblance to a Śiva-liṅga once the spire is removed. Tadhaṃ Bāhā [skt. Dharmacakra Mahāvihāra]. Otu (Wotu). Kathmandu. (Photo: Niels Gutschow).[13] |

Fig. 20. Two Licchavi caityas with empty niches worshipped as Śiva-liṅgas. The Licchavi caitya in the background is mounted on a circular section of another caitya. In front is a tall Caturvyūha Caitya inside a rectangular grooved pedestal (jalaharī). Nandikeśvara Bāhā. Ḍhuṅgedhārā. Naxāl. Kathmandu. (Photo: Ulrich von Schroeder, 2011). |

The practice of worshipping caityas as Śiva-liṅgas is documented at Bodhgayā in the late 19th century, according to a Nepalese Buddhist who visited it, as recorded by Brian H. Hodgson: “In Buddh Gayah there is a temple of Maha Buddha in the interior of which is enshrined the image of Sakya Sinha. This temple of Maha Buddha, the Brahmans call the temple of Jagat Natha [Lord of the World], and the image of Sakya Sinha they name Maha Muni [The Great Sage]. At a little distance to the north of the great Maha Buddha temple are many small Chaityas (Fig. 1), which the Brahmans call Siva Lingas, and as such worship them, having broken off the Chura Mani from each. In Nepaul, the Chaitya is exclusively appropriated to five Dhyani Buddhas, whose images are placed in niches around the base of the solid hemisphere which forms the most essential part of the Chaitya. Almost every Nepaul Chaitya has its hemisphere surmounted by a cone or pyramid called Chura Mani. The small and unadorned Chaitya [with empty niches?] might easily be taken for a Linga like metamorphosis of the Chaitya into a Lingam and its worship as the latter, may now be seen in numerous instances in Nepaul” (Fig. 22).[14] This record clearly documents an apparent custom among Indian and Nepalese Śiva-mārgī to worship altered caityas as Śiva-liṅga.

Fig. 21. Viṣṇu-Caturvyūha with four Śrīdhara aspects of Viṣṇu attached to a shaft reminiscent of a Śiva-liṅga. Mounted on grooved pedestal (jalaharī) and supported by a brick pedestal with the corners fashioned of fragments of Licchavi caityas with empty niches. Nandikeśvara Bāhā. Ḍhuṅgedhārā. Naxāl. Kathmandu. (Photo: Ulrich von Schroeder, 2011). |

Fig. 22. Fragment of a Licchavi caitya worshipped as Śiva-liṅga beside another liṅga mounted inside a circular grooved pedestal (jalaharī) at Paśupatinātha in Kathmandu. Liṅgas are usually mounted upright in the centre of a round, oval, or sometimes square grooved pedestal called jalaharī “small pit of water” with a spout to drain the oblations that serves as bathing-seat (snānapiṭha). (Photo: Ulrich von Schroeder, 1 August 2022). |

According to Mary Shepherd Slusser, the rough back wall of the empty niches is inconsistent with the overall perfection of Licchavi caityas. According to her opinion, either the statues were later removed or they once held removable images of metal or stone, perhaps only installed on occasions.[15] For Ulrich Wiesner, who up to now has made the most insightful study, the rough back walls of the empty niches are the result of iconographical details being chiseled away by Brahmans, as a form of censorship in what he calls an extremely odd phenomenon. He claims that all Licchavi caityas were affected and became ambiguous monuments that could be adapted for other cults. Wiesner’s conclusions are supported by the notion, prevalent among Newar Buddhists, that there was a terrible persecution of Buddhists at the hand of one of the incarnations of the Indian Hindu reformer Śaṅkarācārya.[16] In the opinion of Ulrich Wiesner the reworking must be regarded as a form of censorship and not as an act of destruction.

Mary Shepherd Slusser believed that there exists no historical evidence regarding any purge of Licchavi caityas by Indians.[17] However, as recorded in the Buddhist Vaṃśāvalī quoted by Daniel Wright concerning a certain Śivadeva:[18] “Being a wise monarch, he caused to be uncovered in the city a caitya which Śaṅkarācārya had concealed”.19] It is stated in a recent published Nepālarāja Vaṃśāvalī that “Adi Śaṅkarācārya came from the South and destroyed the Buddha faith during Kali 2614 or 487 BCE. For many critics of the theory that a purge had taken place, the argument remains how could it be possible that beside the numerous depilated caityas with empty niches some caityas survived with the images left unmolested? The Caturvyūha Caitya at the Dhvākā Bāhā in Kathmandu is the most spectacular exception in this respect and thus quoted by all writers. How could the images of the Dhvākā Bāhā Caitya be intact, whereas almost all other Licchavi caityas only bear empty niches. However, none of the writers were aware that the Dhvākā Bāhā Caitya is only installed above ground since 1956/1957 after having remained underground for almost thousand years, which explains the remarkable condition (Fig. 5).[20] The opinion of Niels Gutschow is that in the one case, the figures were fashioned in one piece with the caitya itself, and in the other they were placed into it.[21] According to Bernhard Klöver “the caitya was re-shaped in response to that most common of Śaiva emblems, the liṅga raised in the yoni.”[22] To this we add that three or four Licchavi caityas with intact images is all what there exists, compared to the almost three hundreds dilapidated ones with empty niches.

Ian Alsop states that among the curious puzzles of early Nepalese sculpture and architecture are the empty niches of the Licchavi stone caityas that dot the Kathmandu valley. These elegant caityas are fully decorated, often with exquisitely detailed carvings, but the niches where one might suppose the figures of the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas would normally reside, are vacant. According to Ian Alsop, several explanations have been offered for this puzzling detail of these monuments. One is that the figures originally contained in the niches were destroyed during the week-long Muslim incursion led by Sultan Sham ud-din Ilyas of Bengal in 1349. Ian Alsop further notes whereas the larger images in the niches of large stūpas were designed to be left in situ permanently, metal images were probably only inserted into the empty niche at the time of periodic ritual worship. He illustrates this with several small copper images with tenons protruding from their back.[23] However, he does not address the issue why there is nothing inside any of the thousand empty niches to affix them to it? Ian Alsop is ruling out that there ever was a purge resulting in empty niches after chiseling away the images. Alexander von Rospatt regards empty niches [not as the result of a purge] but rather as a prominent feature of Nepalese caityas and can already be found in the case of Licchavi caityas form the first millennium.[24]

In the relatively small valley of Kathmandu, countless temples and shrines of different religious sects survive. Almost all foreign writers, the author of this essay included, maintained that Hindus and Buddhists lived throughout the history in a relatively peaceful co-existence of the manifold religious traditions. This opinion is not shared among Nepalese historians who point out that there existed a long history of overt and covert conflict between the Hindu majority and the Buddhists minority. Local chronicles abound in reports of religious pogroms and devote much attention to a detailed and vivid account of the destruction of Buddhism by Śaṅkarācārya. This divergence, as one example, is illustrated by ceremonial lamps (tvāḥdevā), which in the case of Hindus bear an image of Gaṇeśa. This contrasts with the Buddhists who light similar lamps crowned with representations of Vighnāntaka, or “destroyer (antaka) of obstacles (vighna)” – a tantric Buddhist deity in the act of subduing the obstacle personified by Gaṇeśa. Unsurprisingly, according to Hindu interpretations, Gaṇeśa is supporting Vighnāntaka. It is significant that Gaṇeśa also known as Vighneśvara the “remover of obstacles”, is considered by the Buddhists to be himself the obstacle to be overcome by Vighnāntaka. The sādhana texts only mention the obstacle to be trampled on, without mentioning Gaṇeśa in particular, although he is clearly identified as such in sculptures and paintings.[25] Royal patronage by the Hindu rulers was never evenly distributed and always favored Hindu communities, whereas the Buddhist communities depended mostly on local patrons.

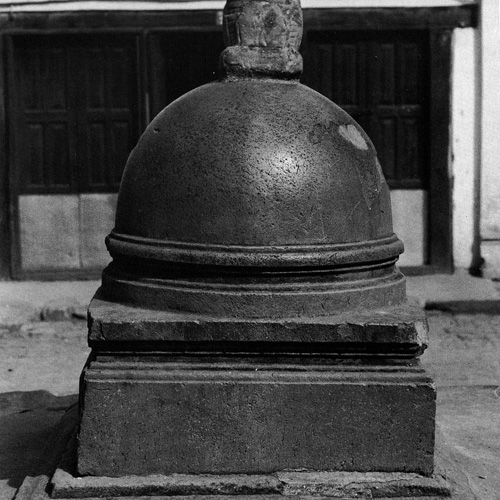

A puzzling change in the design of caityas in the Kathmandu Valley occurred in the mid-19th century as a result of Śiva-mārgī interference as documented by the Jalaharyūparisumerucaityas. These syncretistic caityas, of which seventy-two are known to survive, are mounted in a round grooved pedestal called jalaharī “small pit of water” with a spout as used traditionally for Śiva-liṅgas (Fig. 23).[26] However, the predominantly Buddhist Patan was less affected. Among the Bauddha-mārgī of Patan only one example of a Jalaharyūparisumerucaitya is known to exist among the likely more than thousand caityas located there. This contrasts with the situation in Kathmandu where seventy-one erected under the domain of the Śiva-mārgī survived. The Jalaharyūparisumerucaityas were re-shaped to resemble the most common of Śaiva emblems, the liṅga raised in the grooved pedestal called jalaharī, identified in the Śaiva context as yoni. The Tathāgatas on the four sides correspond to the four faces depicted on caturmukhaliṅgas. The Tibetan teacher Si tu Paṇ chen Chos kyi ’byung gnas («situ panchen chökyi jungney») (1700–1774) remarked regarding the Jalaharyūparisumerucaityas that this caitya, in fact, is a ‘receptacle for offering’ (Tib. mChod rten = caitya) dedicated to Mahādeva [Śiva], the great Hindu god. The caitya is square in shape, made in the form of a vessel with a spout, the inner hub of which, in the shape of a yoni, carries a liṅga in its center — apart from which it is correctly built as a stūpa]. Of this class of caitya, there are great numbers, but one should view them as sacred representations of the Hindus.[27] As documented by the Jalaharyūparisumerucaitya erected in 1869 at the Kirtipunya Mahāvihāra in Kathmandu, syncretism was not restricted to the addition of a round grooved pedestal called jalaharī, but upsets also the iconographical rendering of the four Tathāgatas issuing from the central shaft. Amoghasiddhi is rendered four-armed with the attributes of Viṣṇu, namely disc (cakra), club (gadā), conch shell (śaṅkha), and lotus flower (padma). Ratnasambhava is also rendered four-armed holding attributes of Śiva, the double drum (ḍamaru), the trident (triśūla) as the attribute par excellence of Śiva, the water-flask (kamaṇḍalu), and vibhūti.[28]

Fig. 23. Malla Period caitya erected inside a jalaharī as used for Śiva-liṅgas. Tābāhā, Kathmandu, built 1863. (Photo: Niels Gutschow). |

Almost one hundred years later, in 1967, another syncretistic votive structure in the shape of a Sumeru Caitya was erected in Sānāgāon Village in the Kathmandu Valley. Here the shaft of the caitya is occupied by four standing Hindu gods, namely Viṣṇu with Garuḍa (north), Śiva with the bull (west), Rāma with Hanumān (south), and Kṛṣṇa also with Garuḍa (east). The presence of Śaiva and Vaiṣṇava emblems on this unique caitya represents thus a syncretism of the three principal religious traditions practiced in Nepal. And as stated by Niels Gutschow, with this structure we appear to have come full cycle.[29] Although the syncretistic caityas are not related to the phenomena of empty niches as such, they nevertheless illustrate the lasting interference by the Śiva-mārgī regarding the Buddhist caityas. The political and cultural milieus during these periods evidently show increasing political and cultural fundamental Hinduisation by successive dynasties.[30]

In 1349, an army led by Sultan Shams ud-dīn Ilyās attacked the Kathmandu Valley.[31] This raid lasting seven days wreaked far greater havoc than that incurred by all the earlier Khasa and Maithilī raids put together. The latter at least respected the sanctity of most of the temples and shrines, while the Muslims laid much of valley in ruins, purposely destroying in their iconoclastic fervor many religious monuments after looting them for their sacred treasures. Any hypothesis that Muslim soldiers chiseled out images from caityas instead of just smashing them remains doubtful.

Personally, I always feel somehow uncomfortable coming across votive caityas with mostly crudely executed empty niches while strolling around the Kathmandu Valley. The caityas look mutilated and abused and remind me of ruined buildings in a war-like setting. The only empty niches that occur in Buddhist traditions are those of the Licchavi caityas. There is sufficient archaeological evidence and literary reference to have confidence in that a radical purge had taken place during circa the 9th or 10th century. As traditionally maintained by the Newar Buddhists, the purge focused against caityas was instigated by an unknown reincarnations of the Indian Hindu reformer Śaṅkarācārya. The animosities against Buddhist caityas might have lasted more than a decade as it took time to remove the images from several hundred Licchavi caityas. Originally, most caityas were properly installed on pedestals inside Buddhist compounds. Following the purge many Licchavi caityas were removed from their original settings in Buddhist compounds and dispersed among Hindu locations. For the Newar Buddhists something they must live with.

Select Literature:

Hodgson, Brian. H. 1874. “On the Extreme Resemblance that Prevails between many of the Symbols of Buddhism and Saivism”. In: Essays on the languages, literature, and religion of Nepál and Tibet. (London, Trübner & Co.).

Wright, Daniel (ed.). 1877. History of Nepal. Translated from Parbatiyā by Munshī Shew Shunker Singh and Pandit Shrī Gunānand. (Cambridge: University Press, 1877).

Pal, Pratapaditya. 1974. Buddhist Art in Licchavi Nepal. Marg Publications. Vol. 27. No. 3 (June 1974).

Slusser, Mary Shepherd. 1980. “Nepalese caityas as mirrors of mediaeval architecture”. In: The Stūpa: Its Religious, Historical and Architectural Significance. Edited by A. L. Dallapiccola et al.: 157–165, pls. XI/1–XI/10. Beiträge zur Südasienforschung Südasien-Institut Universität Heidelberg. Band 55.

Wiesner, Ulrich. 1980. “Nepalese votive stūpas of the Licchavi period: the empty niche”. In: The Stūpa: Its Religious, Historical and Architectural Significance. Edited by A. L. Dallapiccola et al.: 166–174, pls. XII/1–XII/14 Beiträge zur Südasienforschung Südasien-Institut Universität Heidelberg. Band 55.

Slusser, Mary Shepherd. 1982. Nepal Mandala: A Cultural Study of the Kathmandu Valley. Two Vols. (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press).

Malla, Kamal Prakash. 1983. “The Limits of Surface Archeology”, Contributions to Nepalese Studies, vol. 11, no. 1: 125–133.

Alsop, Ian. 1997/2000. “Licchavi Caityas of Nepal: A Solution to the Empty Niche”. www.asianart.com/alsop/licchavi.html.

Narayan, Sachindra. 1987. Bodh Gaya: Shiva-Buddha? (New Delhi: Inter-India Publ.).

Klöver, Bernhard. 1992. “Some Examples of Syncretism in Nepal”. In: Aspects of Nepalese Traditions, ed. by Bernhard Klöver: 209–222.

Gutschow, Niels. 1997. The Nepalese Caitya: 1500 Years of Buddhist Votive Architecture in the Kathmandu Valley. (Stuttgart/London: Edition Axel Menges).

Decleer, Hubert. 2000. “Chaityas of the Valley by Niels Gutschow: A Book Review”. In: Buddhist Himalaya: A Journal of Nagarjuna Institute of Exact Methods. Vol. X No. I & II (1999-2000). https://buddhism.lib.ntu.edu.tw/FULLTEXT/JR-BH/bh117558.htm.

Rospatt, Alexander von. 2013. “Altering the Immutable: Textual Evidence in Support of an Architectural History of the Svayambhū Caitya of Kathmandu”. In: Nepalica-Tibetica. Festgabe for Christoph Cüppers; edited by Franz-Karl Ehrhard and Petra Maurer. Band 2: 91–115, 3 plans, 11 pls.

von Schroeder, Ulrich. 2019. Nepalese Stone Sculptures. Vol. One: Hindu; Vol. Two: Buddhist. (Visual Dharma Publications).

Endnotes

1. Hodgson, Brian. H. “On the Extreme Resemblance that Prevails between many of the Symbols of Buddhism and Saivism”. In: Essays on the languages, literature, and religion of Nepál and Tibet. (London, Trübner & Co., 1874).

2. Gutschow, Niels. 1997. The Nepalese Caitya: 284: A jalaharī, if placed below a liṅga, is identified as a yoni.

3. von Schroeder, Ulrich. 2019. Nepalese Stone Sculptures. Vol. One: Hindu: 138

4. von Schroeder, Ulrich. 2019. Nepalese Stone Sculptures. Vol. One: Hindu: 146–147, Plate 35D.

5. von Schroeder, Ulrich. 2019. Nepalese Stone Sculptures. Vol. One: Hindu: Plates 37A–37C, 37E, 38D, 39E, 42E, 42G, 43D, 44A–44B, 44D–44E, 45B, 45F.

6. Slusser, Mary Shepherd. 1982. Nepal Mandala: 224, pl. 337

7. von Schroeder, Ulrich. 2019. Nepalese Stone Sculptures. Vol. One: Hindu: 150–151, Plate 37A.

8. von Schroeder, Ulrich. 2019. Nepalese Stone Sculptures. Vol. One: Hindu: 150–151, Plate 37C.

9. von Schroeder, Ulrich. 2019. Nepalese Stone Sculptures. Vol. Two: Buddhist: 920–921, pls. 285A–E.

10. von Schroeder, Ulrich. 2019. Nepalese Stone Sculptures. Vol. Two: Buddhist: 106, pl. 25A.

11. Wiesner, Ulrich. 1980. “Wiesner, Ulrich. 1980. “Nepalese Votive Stūpas of the Licchavi Period: The Empty Niche”. In: The Stūpa: Its Religious, Historical and Architectural Significance. Edited by A. L. Dallapiccola et al.: 172.

12. Gutschow, Niels. 2012. Architecture of the Newars. Vol. I: The Early Periods: 53–56.

13. Gutschow, Niels. 1997. The Nepalese Caitya: 116–117, fig. 234.

14. Hodgson, Brian. H. “On the Extreme Resemblance that Prevails between many of the Symbols of Buddhism and Saivism”. In: Essays on the languages, literature, and religion of Nepál and Tibet. (London, Trübner & Co., 1874)

15. Slusser, Mary Shepherd. 1982. Nepal Mandala: 172.

16. Wiesner, Ulrich. 1980. “Nepalese Votive Stūpas of the Licchavi Period: The Empty Niche”. In: The Stūpa: Its Religious, Historical and Architectural Significance. Edited by A. L. Dallapiccola et al.: 166–174, 14 pls.

17. Slusser, Mary Shepherd. 1982. Nepal Mandala: 49.

18. Perhaps Śivadeva/Siṃhadeva (reigned c. 1100–1123).

19. Wright, Daniel (ed.). 1877. History of Nepal. Translated from Parbatiyā by Munshī Shew Shunker Singh and Pandit Shrī Gunānand. (Cambridge: University Press, 1877): 126 [footnote 32].

20. According to a personal communication by Sukra Sagar Shrestha the Dhvākā Bāhā Caitya was found while cleaning the Ikāpukhu sometimes in 1956/1957 on the day of Sithinakhah that falls in the month of June on which every well, pond and Hiti were cleaned until 1970’s.

21. Gutschow, Niels. 1997. The Nepalese Caitya: 109–110.

22. Klöver, Bernhard. 1992. “Some Examples of Syncretism in Nepal”. In: Aspects of Nepalese Traditions, ed. by B. Klöver: 216. [Quoted by N. Gutschow].

23. Alsop, Ian. 1997/2000. “Licchavi Caityas of Nepal: A Solution to the Empty Niche”. www.asianart.com/alsop/licchavi.html.

24. Rospatt, Alexander von. 2013. “Altering the Immutable: Textual Evidence in Support of an Architectural History of the Svayambhū Caitya of Kathmandu”. In: Nepalica-Tibetica. Festgabe for Christoph Cüppers; edited by Franz-Karl Ehrhard and Petra Maurer. Band 2: 101.

25. Bhattacharyya, Benoytosh. 1958. The Indian Buddhist Iconography: 180–181; Mallmann, Marie-Thérèse de. 1975. Introduction à l’iconographie du tântrisme bouddhique: 447–450.

26. Gutschow, Niels. 1997. The Nepalese Caitya: 301, fig. 562: Jalaharyūparisumerucaitya at Tābāhā, Kathmandu. Built 1863.

27. Situ Panchen. The Autobiography & Diaries of Situ Panchen (Tibetan Text), Lokesh Chandra, ed.; introduction by Gene Smith). (Delhi: International Academy of Indian Culture 1968). [Quoted by Hubert Decleer, 2000.

28. Cf. Gutschow, Niels. 1997. The Nepalese Caitya: 36–37, figs. 34–37.

29. Gutschow, Niels. 1997. The Nepalese Caitya: 285, fig. 530.

30. Malla, Kamal Prakash. 1983. “The Limits of Surface Archeology”, Contributions to Nepalese Studies, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 126. [Quoted by H. Decleer].

31. Petech, Luciano. 1984. Mediaeval History of Nepal (c. 750–1480): 125–127.

asianart.com | articles