The Future of Nepal’s “Living” Goddess: Is Her Death Necessary?

by Deepak ShimkhadaSeptember 10, 2008

Introduction

Many sensational articles have recently appeared in the Western media, some with titles such as “Kumari in Peril,” “Kumari Sacked from Her Throne,” “Nepal’s Living Goddess Retires,” and “Nepal’s Living Goddess May Die Soon.” The last title may prove to be prophetic because Kumari, as a tradition, is about to become extinct, if elements of Nepal’s new government and some Western human rights groups have their way.

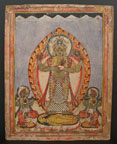

The temple of Kumari, a living embodiment of the Hindu goddess Durga, has been a significant shrine of national importance in Nepal for over three centuries. Ever since Nepal was thrown open to the world with the abolition of the Rana dynasty in the mid twentieth century, the temple has also increasingly become a popular tourist attraction. The admixture of politics and religion is not a new phenomenon in the history of Nepal, but for ages the Valley has also been an exemplar of Hindu-Buddhist unity. The blatant attempt by the new government to eliminate a popular religious and cultural institution is both unnecessary and unwelcome.

While the temple itself is only three centuries old, the tradition of worshipping the goddess in a virgin form in South Asia and among the Hindus is over two millennia old. Not only was the ancient shrine to her at Kanyakumari (the virgin maiden) at the southern tip of the Indian subcontinent well known to the Romans, but the worship of a virgin girl is an essential part of the autumnal worship of the goddess Durga. Nowhere is this religious festival more important than in Bengal among the Bengali speaking Hindus where a virgin girl is the center of the celebration. The Maoists of Nepal should note that the Communists who have been ruling West Bengal for over two decades have not abolished the tradition.

Although the worship of Kumari was officially instituted by King Jayaprakasha Malla (1736-1768) of Nepal in 1757 by building a permanent shrine for her in the heart of the Kathmandu Durbar Square, Kumari’s origin can be traced to King Trailokya Malla (1560 –1613) of Bhaktapur in the sixteenth century. According to a popular legend, it was this king who instituted the tradition of Kumari after forfeiting the right to see Durga in person. [1] However, the Goddess Taleju, who was believed to have been brought to the Kathmandu Valley by King Hari Singh Deva in 1323 from Simrongarh, [2] remained a tutelary deity of the Malla dynasty as well as of the Shah Kings. Taleju was recognized as a form of the Goddess Durga, who appeared in human form in front of King Trailokya Malla every night. The king and the beautiful goddess played a game of dice (tripasa); this continued for some time until one night, overcome by desire, the king made sexual advances toward the goddess. When this happened, the goddess disappeared. The king then felt remorse, but Taleju appeared in the king’s dream and told him that she would appear in the body of a virgin girl of the Shakya caste, a Buddhist by faith, who would bless him every year. The Kumari in her present form is the embodiment of the Goddess Durga. As can be seen, the Kumari tradition not only has historical and religious foundations, but embodies a clear attempt by a ruler to bring Hindus and Buddhists together in harmonious coexistence.

Every September during the Kumari chariot festival (Ratha Jatra), the Malla king would go to Kumari’s residence to receive her blessings. With her blessings the king was given the mandate to rule for another year. Kumari’s Ratha Jatra actually coincides with the Indra Jatra, the festival of Indra (of Vedic origin) to signal the end of the monsoon season. In the Kathmandu Valley the monsoon brings more rain than necessary, and therefore the end of the rain is a welcome sign. There is no better way to celebrate this than with a festival dedicated to Indra, the Vedic God of Rain, and to Kumari, the Living Goddess, who assures prosperity.

Prithvi Narayan Shah of Gorkha in West Nepal, the founder of the Shah dynasty that was deposed in 2008, vanquished the Malla kings, [3] but retained the custom of worshipping Kumari, making the goddess the protector of his own dynasty. Prithvi Narayan Shah, technically an outsider, was smart enough not only to recognize the wisdom of continuing an established tradition that fostered unity among the two religious communities but also contributed to his own legitimacy.

From the time of the Malla kings in the sixteenth century to the time of the Shah Kings in the twenty-first century, Kumari has played the role of the protector of Nepal’s rulers. However, as Nepal assumes a new identity as a republic, and the role of the king comes to an abrupt end, [4] should the new changes abolish some of the age-old traditions that are neither burdensome to the state nor harmful to society? The Maoist party, which has taken a lead role in the forming of a new government, believes in principle neither in organized religion nor in religious institutions. The Maoist lawmaker and winner of a seat in the constituent assembly election, Janardan Sharma, recently declared, “All institutions associated with the royal family and feudalism will have to be changed. The Kumari is not an essential institution for the new Nepal.” [5] Since Kumari is intimately associated with the royal house of Nepal, she falls into the category of institutions to be abolished. But Kumari is not the only religious institution that is closely related to royalty. What about Pashupatinath and even Macchendranath?

It should also be noted that the new Nepal governemnt is not monolithic in regard to the question of the further existence of the Kumari, and Janardan Sharma’s views are not shared by all elements of the government. When the Constituent Assembly elected Rama Baran Yadav as the country’s new president – a new post which replaces some of the king’s role as head of state – one of his first acts was to take darshan and blessings of the Royal Kumari, which he did on July 22, 2008.

President Yadav also went some days later “with full state fanfare” to witness the showing of the bhoto of Macchendranath at Jawalakhel in Patan, another duty of the king in the past. This act was the subject of a critical article in one of Nepal’s major English dailies, The Kathmandu Post, whose author opined: “Political parties have to be more progressive, forward looking and consider just how they can manage to keep the top job of the secular state free of any attachment to religious traditions.” [6]

Controversy

Today, in the name of modernity, some members of human rights groups and the newly elected government are proposing that the Kumari tradition be abolished for good. Although the tradition of a living goddess is also known in India, the personification of Goddess Durga's maiden virginity in a Buddhist girl and the annual festival associated with her is unique to Nepal. The roots of the Kumari tradition and why she has become a pawn in the power struggle are significant phenomena to examine. In this short paper I will argue against abolishing the Kumari tradition from cultural, social, and economic perspectives.

My interest in this subject was sparked by a BBC report. [7] I was so much moved by the news that I wrote a letter to the Kathmandu Post, which published it the same week. Scott Berry, an American writer who coauthored the book From Goddess to Mortal with Rashmila Shakya, [8] a former living goddess, emailed me in support of my position on the issue.

The BBC article reported that the petition to the court to abolish the Kumari tradition was filed last year by a human rights group on the grounds of exploitation and psychological damage suffered by the girls selected as Kumaris. Chunda Bajracharya, a researcher on Newar culture, told the BBC that the tradition has not affected Kumaris' individual rights. In fact, it has elevated their status in society as "someone divine, someone who's above the rest." The court in its wisdom asked that a committee consisting of experts on Kumari be formed. This body has been charged with coming up with recommendations. Based on these recommendations, the court will deliver its verdict. While the petition is pending in the court, the controversy has escalated because the political climate of Nepal has suddenly changed. What effect this will have on the fate of the Kumari is not hard to guess, given the temperament of some parties of the government. Hopefully the judiciary will remain neutral.

It is true that the girls selected to be Kumaris are separated from their families and are required to live in the Kumari House until they complete their term. The fact that these young girls, who would otherwise be in school playing with their friends, are suddenly removed from a conventional social environment and kept in a controlled environment may indeed be an issue for discussion. However, we have to weigh the other benefits accorded to the young girls, such as special care, veneration, security, and home schooling, which they otherwise would not likely receive. Also, let us not forget that the girl’s parents are often allowed to live with the Kumari at her residence to avoid any emotional problems. Although she may not have the freedom to go out to play or do chores like any normal girl of her age, she is kept sufficiently occupied in her residence by her caretakers. The human rights group has charged that the Kumaris have been exploited, but they failed to explain exactly how and by whom.

Such terms as "exploitation" and "psychological damage" are loaded with ambiguities. Have members of the group really researched the situation of the Kumaris? Have they interviewed the Kumaris to see how they feel about this issue? What is the actual percentage of girls that do not marry after they leave the Kumari House? What is their mental health while they try to lead a normal life? If there is a preponderance of evidence to suggest that they indeed suffer emotional damage because of social discrimination and cultural victimization, then we need to find ways to rehabilitate them by providing vocational training, jobs, and a retirement package so that they may be reintegrated into mainstream society. Doing away with the Kumari tradition is not the answer.

In the book authored by Rashmila Shakya, the former Royal Kumari, and the two recent documentaries on Kumari produced by Western filmmakers that I have seen, [9] there is not a shred of evidence to suggest that any former Kumari felt that her experience was a negative one. In open interviews, all former Kumaris, including the oldest surviving Kumari (Hira Lal Shakya, who was said to be eighty-five years old when the documentary was made in 2005), enjoyed their role as a Kumari and never regretted it. So what is the fuss? They all felt empowered and special, even if only for a few years. If the Kumaris do not feel that they have been exploited, isn't the human rights group acting as Big Brother? Is this really such a significant social problem of Nepal that it requires court intervention?

Opinion

Nepal has many social problems. Here are a few: Girls are being sold into prostitution every day. In some parts of the country, girls who are barely thirteen years old are being married to much older men. These girls tend to become pregnant at a young age, exposing them to birth complications and even death. Most girls are not given the opportunity to get an education. Instead of attending school, many underage girls are forced to work. These are not practices essential to Nepali religious tradition. Abolishing the Kumari tradition will not solve these more serious problems.

By doing away with venerated, age-old customs, elements of the new Nepali government and some human rights organization may be going down the path to wiping out their culture, history, and identity as Nepalis. Cultural identity is more important than political identity. As we move toward assuring essential human rights for all, we should preserve those customs that make us who we are. As a Nepali, I certainly hope that the newly elected government in power will think twice before abolishing cultural traditions that add value to the country’s heritage and prestige, and bring financial gain to the country through tourism. Although Kumari was traditionally associated with the throne, she does not have to disappear just because Nepal has voted to abolish the monarchy. Judging by the situation on the globe all heads of states could do with the blessings of a living goddess. The people of Nepal, who need and seek peace, harmony, and reconciliation, need Kumari’s blessings more than ever.