asianart.com | articles

Download the PDF version of this article

Microcosm of Kathmandu’s Living Culture and Storied History

by Dipesh Risal

text and photos © asianart.com and the author except as where otherwise noted

September 03, 2015

(click on images to go to larger image and full captions)

Kasthamandap is no more. It collapsed into a pile of rubble in the first of the earthquakes that rattled Nepal in April-May, 2015. Kasthamandap (literally Wooden Hall), originally a public rest-house (sattal), has also served many social and religious functions over its lifetime. It was easily the oldest standing building in all of Nepal, dating back to at least 1143 CE. Kasthamandap underwent numerous repairs, remodeling, and renovations over the centuries. However, the large platform with its surrounding quartet of tall, one-piece, “ship-mast” pillars and carved capitals – collectively making up its defining core – most likely date from the original foundation. Kasthamandap is also the largest structure ever built in the traditional triple-tiered roof style. In Nepal, its grand interior space was never surpassed until the eighteenth century. Further, it alone preserves the original configuration and may have established some sort of prototype for a suite of sattals built during the fourteenth through sixteenth centuries. [1] Although it housed several shrines, Kasthamandap was primarily devoted to multiple secular functions: rest-house, council hall, social center, marketplace, and more.

In local tradition, the building is fondly referred to as Maru (Madu)-sattal, after the name of the surrounding tol (neighborhood). It is likely that during its original founding, or in the early centuries of its existence, the sattal also acted as a marketplace. Indeed, the open spaces around Kasthamandap, through Indra Chowk and all the way to the Asan Tol are still thriving marketplaces to this day. In this context, it is worth mentioning that one of the twin sattals flanking the ancient fountain Manidhara in Patan was the municipal weighing house, as well as the place where market prices were fixed.[2] All this gives special resonance to the legend attached to Kasthamandap’s founding, according to which the locals should shout loudly during the annual sattal puja (ritual worship) that the price of salt and oil were still not the same. [3] The shouting is related to the belief that the divine tree god Kalpavriksha, who had procured the tree from which Kasthamandap was constructed, was bound by a promise to remain in the locality until the day the price of salt and oil would become the same. The legend supports the view that Kasthamandap, or at least the area around it, was a marketplace. So does a watercolor from the1860s by Oldfield (see fig. 1).

Fig. 1: “The Market Place, Kathmandu,” 1860s watercolor by H. A. Oldfield.

Kasthamandap occupies a central location in Kathmandu valley, at the intersection of two ancient towns known as Koligrama and Daksina (south) Koligrama (and later as Yambu and Yangal).[4] Moreover, Kasthamandap sits squarely at the crossroads of the ancient trade route that connected India with Tibet and the principal North-South road of Kathmandu. Within a few yards of Kasthamandap, and also flanking the ancient crossroads sit two other sattals, Laksmi Narayana Sattal (17th c) and Silyan (Singha) Sattal (16th c, although legend claims this one is as old as the original Kasthamandap).[5] Together, the three sattals at the heart of the valley must have catered to the traffic at the crossroads, much like motels that are found at the junction of major modern highways in the US.

Fig. 2 : The ancient trans-Himalayan trade route crossed the main Kathmandu North-South road at Kasthamandap.

Given all this, if Kasthamandap is not restored, and the associated historic treasures are not found, Nepal will lose a significant part of its heritage and identity. Forever. Unfortunately, most Nepalis believe Kasthamandap was built many centuries later. The misperception of Kasthamandap s age stems from 19th century Kathmandu vamsavalis (chronicles), which without fail, and for some inexplicable reason, credit Laxmi Narsingh Malla (ruled 1621-1641 CE) for the establishment of this monument. The rigorous Samsodhan Mandal research group had correctly established the antiquity of Kasthamandap more than twenty-five years ago.[6] However, the incorrect later dating has been cited and perpetuated in many Nepali and Western publications.

Let us, then, recollect the established historic evidence of Kasthamandap, a building of such importance it has been recognized as “the singlemost (sic) important building of Kathmandu.”[7] Let us also act immediately to seek out what remains, and to restore the sattal to its rightful place at the heart of old Kathmandu.

Fig. 3: Kasthamandap ruin showing a makeshift mandap. Photo Sameer Tuladhar

First tentative mention of Kasthamandap: 1090 CE (Nepal Sambat 210)

A manuscript of the Astasahasrika-Prajnaparamita, with a colophon dating it to 1090 CE, was discovered by Mary Slusser and Gautama Vajracharya when they were researching Kasthamandap in the early 1970s. As of 1974, as reported by them, the manuscript was in possession of a social organization (guthi) associated with Kasthamandap; guthi members claimed at that time “that the manuscript contains a history of the sattal, its foundation and subsequent renovations” but it was not made available to the authors for more than a brief perusal.[8]It is possible that the guthi manuscript survived the 2015 earthquake because of being stored away from Kasthamandap. Locating and studying the manuscript may provide crucial evidence supporting the sattal’s antiquity.

First confirmed mention of the name Kasthamandap: 1143 CE (263 NS)

The polymath Rahul Sankrityayan, traveling under great duress to Tibet in 1936, found in the Sakya monastery a worn-out palm-leaf copy of the manuscript Namasangiti.[9] The colophon of this manuscript contains the words Sri Kasthamandape and is the first confirmed record of the place name “Kasthamandap” to date. According to Petech’s reading of the text, this manuscript copy was completed in Brahma Tol, Kathmandu in “the last hours of Friday, September 24th, 1143” during the reign of Narendra Deva.[10] He was the third ruler of the Licchavi or Transitional Periods to bear that name and reigned from about 1140 to 1147 CE.It is not illogical to assume that the place name Kasthamandap was derived from the large, well-known sattal of the same name that dominated the local landscape. It is also not illogical to surmise that the construction of the building itself preceded the first recorded mention in 1143 CE by many years - at least as many as fifty-three, if the 1090 CE manuscript reference is confirmed. The geographic extent of Kasthamandap was originally limited to the area around the sattal, but eventually grew to cover the entire northern city (formerly known as Koligrama, then Yambu), and by the fourteenth century, the unified Kathmandu city.

How did this manuscript make its way into Tibet? We will never know. Did it ride the back of a porter to survive the rain and snow along the way? Did it stay warm in the bosom of a pilgrim traveling back home after earning much religious merit in Nepal?

Fig. 4: Capital of one of the four central ground-floor pillars. Photo Mary Slusser 1970

Cultural Capsules in Copper

The most valuable set of Kasthamandap treasures are the copperplate inscriptions (tamrapatra) that were physically affixed to the beams or façade of the sattal. Beginning in the Licchavi period, inscriptions have been used in Nepal as contemporary “press releases”, through which kings promulgated their edicts, recorded heroic deeds and socio-religious acts, and their subjects made known the meritorious acts by which they and all beings earned religious merit.The Licchavis placed such inscriptions on stone slabs (silapatra) set up in well-frequented places such as public fountains and water tanks, and the pedestals of sacred images.[11] Sometimes, too, they engraved inscriptions on the pedestals of bronze images or on the gilt copper repousse coverings of stone images.[12]

Copperplate inscriptions also existed in Licchavi times, but recorded history captures an increased frequency of them during the Transitional Period (879 – 1200 CE).[13] Most inscriptions, whether carved on stone or engraved on copper, were placed in public places where a maximum number of city dwellers would be able to see them. It is therefore not surprising that the local elite chose Kasthamandap for many of these copperplate inscriptions, due to the sattal’s location at the heart of the Kathmandu Valley. In doing so, these copperplate inscriptions fortuitously captured a wide variety of themes, ranging from concrete evidence of historically significant events, to slow-moving transitions in the cultural or religious landscape, and even poignant vignettes of contemporary Nepali society. Of them, the oldest one is so rich a capsule of contemporary society and culture that it deserves a detailed analysis, at least of the first three lines.

Oldest copperplate inscription attached to Kasthamandap: 1333 CE (454 NS)

This copperplate inscription was affixed to the front wall of Kasthamandap during the reign of Arimalla (II). It is the oldest physical record that directly links the name “Kasthamandap” to the sattal.भह्नाह्नस सुदिस श्रीत्याछ तवतवमी संमतन जुर उदैशन थितिलोपन

याङ थाक्र थितिथिरा रपरंगा भाष थ्वते जुर् वं। श्रीपांचालि भह्नाह्नस श्रीगछे त...[14]

Let it be auspicious. In [Nepal] Sambat 454, on the eleventh lunar day of waning [fortnight of the month of] Marga, at Yangal. The auspicious building of the three royal families, the deity Panchali.[15]

Yangal is the southern sector of Kathmandu as noted previously. Tribhaya chem translates as “building of the three royal families” and probably points to use of the sattal as a royal council hall by three contemporary ruling families. In this regard, it is worth noting that Manimandapa - one of the twin sattals flanking the ancient Patan fountain Manidhara - was used as a royal council hall and occasional coronation place of kings.[16]

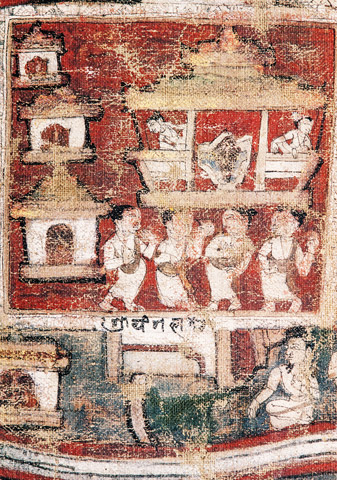

Fig. 5: Detail of a 16th c. pata showing Yangal.

Photo Mary Slusser

Panchali is a reference to Lord Pachali, who is “petitioned as the divine witness to a political pact and made guardian of certain funds deposited as a gage in his temple, the sattal”.[17] In keeping with a common Kathmandu tradition, the building has probably always been both a shrine and a public hall. Pachali Bhairav is a much revered deity particular to the southern half of Kathmandu to this day.

This copperplate is valuable not only because of its antiquity and content. It is also one of the first records of the use of Nepal bhasa (along with Sanskrit) in court-sponsored writing, and captures a medieval Kathmandu transition during which manuscripts and inscriptions slowly changed from being fully in Sanskrit during the Licchavi period to also incorporating Nepal bhasa (Newari), and by the end of the fifteenth century Nepal bhasa was beginning to supplant the previously dominant Sanskrit.[18]

In addition to serving as a public rest-house, and being associated with local royal families and the deity Pachali, Kasthamandap also has long-standing Buddhist connections. As of 1974, a Buddhist guthi still performed panchadana (five offerings) on bhadra chaturdasi at the site, during which is displayed, among other things, the Astasahasrika-Prajnaparamita manuscript from 1090 CE mentioned above.[19] One can only hope that despite Kasthamandap’s fall, there will be a panchadana at the site during this year’s bhadra chaturdasi in September, 2015. This would be an excellent opportunity to confirm the existence – and to document the contents – of the 1090 CE manuscript.

Fig. 6: Frieze details from Kasthamandap: a group of monks worshipping the Buddhist stupa (above) and

another group of devotees worshipping the Shiva Linga (below). Photo Mary Slusser 1970

The Gorakshyanath Connection

For many decades beginning in 1953[20], scholars had read the phrase “devo gorakṣo” at the beginning of another copperplate inscription from 1379 CE (499 NS) leading them to associate Kasthamandap with Guru Gorakshyanath, and the Nath cult (more on this below). Indeed, working off the imperfect transcription and lack of access to the physical copperplate inscription, Slusser and Vajracharya translated the available transcription thus:However, the Nepali scholar Kashinath Tamot, working off a subsequent photograph of the inscription, claims that the phrase “devo gorakṣo” as read by previous scholars is actually “vesakha shukla” (second lunar day of waxing fortnight of the month of Vaisakha), concluding that Kasthamandap was not given to Gorakshyanath as claimed by other scholars.[22] K.P. Malla also supports this interpretation.[23] While we may accept the absence of “devo gorakṣo” from the inscription, the occurrence of “harigana” (a common name for followers of the Nath cult) in the inscription leaves open the possibility of a Gorakshyanath association. Certainly, a later Kasthamandap copperplate inscription from 1465 CE (585 NS) confirms the dedication of Kasthamandap to Gorakshyanath and his gana (followers).[24]

The Nath cult, focused on worship of Shiva, originated in India during ancient times and was an extremist branch of Pashupati ascetics called Kapalikas. In the Kathmandu valley, the Nath cult, with its veneration of Gorakshyanath, flourished between 1367 CE to 1482 CE, as documented in numerous inscriptional references.[25]

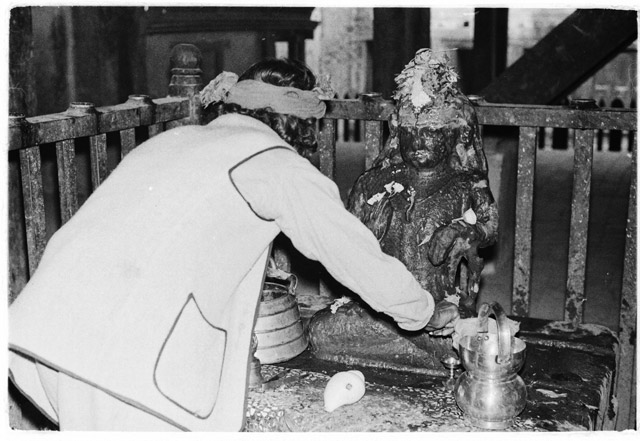

Fig. 7: Nath yogi performs puja (worship) of the Gorakshyanath statue. Photo Mary Slusser 1970

Gorakshyanath is believed to have traveled to Kathmandu himself. We can assume that his arrival was warmly received by rulers and valley dwellers who always had a soft spot for Shiva, who in the guise of Lord Pashupatinath was one of the principal patron gods of their enchanted valley. On a side note, a small and then-insignificant hill state to the west of the Kathmandu valley, known as Gorkha, had also incorporated Gorakshyanath as their patron saint.

Descendants of the Nath yogis, popularly called kanphatta (slit-eared, because of their ears slit to accommodate circular crystal earrings), still lived within Kasthamandap as of 1966, when they were evicted for renovation of the building.[26] Members of the Kusale caste of Kathmandu also trace their origins to the Nath sect.

In keeping with another Kathmandu theme, Gorakshyanath himself is considered a disciple of Matsyendranath, who is associated as closely with the Buddhist pantheon as he is with the Hindu one; Matsyendranath plays a monumental role in Kathmandu Valley history and culture, his story a subject to which justice cannot be done in these few pages.

The stone statue of Guru Gorakshyanath that occupied the center of the main floor of Kasthamandap may have been a gift from Jayasthiti Malla dating to the same time as the NS 499 1379 CE inscription. Gorakshyanath is usually represented only in symbolic form, with his paduka (imprint or relief of feet). The stone statue therefore is extremely rare, and is one of only two known images in the Kathmandu valley. The signature slit ear of kanphatta yogis is a salient feature in the Kasthamandap statue.

Very recently we have heard that this rare and precious historic statue was recovered from the rubble and is now stored in the Hanumandhoka Museum, although some reports state that perhaps only the upper half of the statue was recovered and obtaining a photo has not yet been possible.[27]

As for the 1379 CE copperplate itself, it was already significantly damaged pre-earthquake, but we can hope that the diligent workers of the Archeological Department will recover this as well.

More Stories in Copper, More History

One copperplate inscription, from the time of Jayajyoti Malla’s rule, was written in Patan on Friday, June 18, 1423 and brought to Kathmandu.[28] One can see hints of Patan’s fame as a metalworking center in this small historic record.Interestingly, the three copperplate inscriptions just noted belong to a continuous line of Malla descendants: Jayasthiti (ruled 1382-1395 CE), Jayajyoti ruled (1396-1428 CE) and Yakshya Malla (1428-1482 CE). This stability might be a reflection of the famously stable rules of the first and third kings.

Another copperplate inscription from 1485 CE (605 NS) contains the lines:

अद्य वाराहकल्पे, वैवश्र्वतमन्वन्तरे, श्रीकलिजुगे, जम्बुदीपे।

भरतखण्डे हिमवत्पादे वासुकिक्षेत्रे, श्रीनेपालदेशे, पशुपति सन्निधाने, वाग्मत्या:

पश्चिम्कूले विष्णुमत्या पूर्वकूले, इहैव स्थाने, श्रीकाष्ठमण्डपनगरे,

श्रेयो∫स्तु सम्वत् ६०५ अश्विनिशुक्लचतुर्थ्यायान्तिथौ। अंगारवासरे।

भाषा सिवलितिन लिलावरङाव जोगी भलादत्वंसकल लिथ्यनङाव,

चक्र बिययातं किटनद्वंबू रोव ४ तलपतिसमत। थ्व बूया वाससन द्वथ्यम्

ब्रषम्प्रत्ते बसवम् चक्र बिम्य निस्त्रप निर्ब्वाहरप यन्जमाल। [29]

Let it be better. During the victorious reigns of Sri Sri Jaya Ratna Malla Deva and Sri Sri Jaya Ari Malla Deva. Today, in Baraaha Kalpa… during the Age of Kali, In Jambu Island, In Bharatkhanda, at the base of the mountains, in the territory of [serpent] Vasuki, in the auspicious country of Nepal, beside Pashupati, along the western banks of the Bagmati, along the eastern banks of the Bishnumati, here in the city of Kasthamandap. Let it be auspicious. 605 NS, the fourth lunar day of waxing [fortnight of the month of] Ashwin, on this Tuesday. [30]

The opening line suggests that two of Yakshya Malla’s sons, Ratna and Ari Malla, were joint rulers of Kasthamandap at that time. Behind this bland official “press-release” lies a tale of intrigue and conflict that was to eventually see the Malla kingdom formally divided into three. In 1482 CE, Yakshya Malla had died, leaving the Valley to his six sons, who were to rule jointly, thus preserving the integrity of the Malla Kingdom. However, before three years had passed, one of his sons, Ratna Malla seized Kathmandu and declared it an independent state. He ruled it jointly with his brother Ari Malla for a period, then wrested all control and ruled singly to 1520 CE. The infighting among these brothers and their descendants lasted all the way until 1769 CE, at which date an invading king from the previously insignificant hill state of Gorkha changed the course of Kathmandu history once again.

Returning, then, to the copperplate inscription in question, what follows is an expansive description of the location of Kasthamandap, the city. The inscription demonstrates that the city of Kasthamandap of the period was bounded by the western banks of Bagmati and the eastern banks of Bishnumati. By 1485 CE, then, the prior Yangala and Yambu sectors had morphed into a single city-state and had adopted the sattal’s name as its own.

The details are interesting. But it is the sustained eloquence of the Sanskrit text here that rivets a Nepali’s attention. The spatio-temporal definition begins with a large canvas, naming the contemporary epoch and the continent of interest. Then in spheres of influence growing smaller, more familiar, more personal, the writer seems to nudge us emotionally towards the center. The suspense builds with each closing in. Now we are in the realm of influence of the serpent Vasuki…now we arrive at the country of Nepal…We pay our respects to Pashupati…We lean forward a bit in anticipation and voila arrive at the center, right at the city of Sri Kasthamandap. Along the way, the two rivers of Bagmati and Bishnumati demarcate Kathmandu using their flowing feminine forms, and somehow seem to relieve the rigid mathematical intensity of the concentric spheres.

Returning to the subject at hand, yet another Kasthamandap copperplate inscription, from 1512 CE (632 NS), this one plated with gold, contains the words pla and karsha.[31] As pla and karshapana in the Licchavi period, these terms referred to coinage. But Petech suggests that in the later Malla use the words denote measures of weight.[32]

In addition to the richly storied copperplates, Kasthamandap housed a copper pot with a 1417 CE (537 NS) inscription that records an order to provide two manas (approx. 800 grams) of beaten rice to pilgrims who had made the arduous journey to Gosainkunda and back.[33] This Saiva pilgrimage site in the mountains north of Kathmandu is still very important to many Valley dwellers, and one can imagine its merit-accumulating potentials for the disciples of Gorakshyanath. In fact when the pilgrimage is made at the August full moon an image of the deity goes with the pilgrims.[34]

In Summary:

1. Kasthamandap was a public sattal that gave Kathmandu its name and its very identity.

2. Kasthamandap was at least 900 years old and possibly more than a thousand, at the time of the 2015 earthquakes. It was therefore the oldest building in Kathmandu and anywhere in the entire surrounding Valley. It was also the largest traditional building.

3. With the fall of Kasthamandap, we have lost an incomparable monument, six copperplate inscriptions and one storied copper pot crucial to its history: The inscriptions are between 682 and 503 years old. Further, the core mandap and four surrounding pillars with carved capitals almost certainly date from the foundation, at a minimum 900 years ago. In addition, some of the carved columns, bricks and other building material, now lost, could possibly be equally old. [Note: As of the publication of this article, some portion of the statue of Gorakhshyanath, at least one of the four Ganesh sculptures, a few of the larger wood columns, pillars and some balcony details have been rescued. However, the rest of the treasures are still unaccounted for, though we have hopes that the workers of the Archeological Department will recover some if not all of them.]

4. Kasthamandap was a time-capsule of old Kathmandu, capturing by way of its inscriptions the contemporary practices of disseminating knowledge through “press-releases” inscribed in copper, confirming the existence of the two townships of Yangal and Yambu, and showing the gradual merging of these local townships into the unified city-state of Kasthamandap (now Kathmandu). Further, the inscriptions establish the association with Pachali Bhairav, illustrate the rise and longevity of the Gorakshyanath cult, reveal the ascendancy of Nepal bhasa as a state language, show the long-standing Buddhist connections, and indicate the dual-kingship sometimes in effect during the Malla era. And lastly, the inscriptions reveal the continuum of culture in Nepal through the endurance of centuries-old Licchavi system of coinage/weights, and clarify the importance of guthi associations still so very relevant in Kathmandu.

5. Kasthamandap, occupying the heart of present-day Kathmandu, is an integral part of Nepal's heritage. It lived through the evolution of Kathmandu, and was an active participant in it. Moreover, Kasthamandap likely served as an early prototype for rest-houses to fulfill various religious and cultural requirements of an evolving city nucleus during the Transitional and early Malla periods.[35]

6. As such, it is also one of the most important buildings in the history and development of traditional Newar architecture.

Let us locate the treasures lost in the debris of Kasthamandap, and let us rebuild it back to its original iconic status. Modern engineering technologies can make the structure earthquake-resistant, while also respecting important local beliefs and building practices. If we do not act, a significant part of Nepal's heritage will be lost forever.

To learn more about Kasthamandap, and to get involved in its restoration, visit www.rebuildkasthamandap.com (where a version of this article originally appeared).

The author would like to thank Ian Alsop for his help in preparing this article and in locating photographs, Mr. Kashinath Tamot and Dr. Gautama V. Vajracharya for help with copperplate inscriptions and manuscripts, Dr. Niels Gutschow for helpful insights, and Neil Greentree for scanning images. Last but not the least, thanks to Dr. Mary Shepherd Slusser, doyenne of Nepali culture and art history, for her infectious dedication to Kasthamandap, introductions to the above scholars, guidance, edits, and access to records including her valuable photographs.

Footnotes:

1.Neils Gutschow, Architecture of the Newars: A History of Building Typologies and Details in Nepal (Chicago: Serindia, 2013), Vol II, 331, 359-60, 373.

2. Wolfgang Korn, The Traditional Architecture of the Kathmandu Valley (Kathmandu: Ratna Pustak Bhandar, 1998), 92.

3. Daniel Wright, History of Nepal (Cambridge: University Press, 1877), 211. See http://www.rebuildkasthamandap.com/legend for a stylized retelling.

4. Mary Shepherd Slusser, Nepal Mandala: A Cultural Study of the Kathmandu Valley, (Princeton: Princeton, 1982), Vol I, 89.

5. Neils Gutschow, Architecture of the Newars: A History of Building Typologies and Details in Nepal (Chicago: Serindia, 2013), Vol II, 345.

6. Dhanavajra Vajracharya, ed., Itihas Samshodhanako Pramana Prameya (Lalitpur: Jagadamba Prakasan, 1962) Part I, 110.

7. Neils Gutschow, Architecture of the Newars: A History of Building Typologies and Details in Nepal (Chicago: Serindia, 2013), Vol 1, 125.

8. Mary S. Slusser and Gautamavajra Vajracharya, “Two Medieval Nepalese Buildings: An Architectural and Cultural Study”, Artibus Asiae 36-3 (1974): 207, fn 34. See also Luciano Petech, Mediaeval History of Nepal (Rome: Istituto Italiano Per Il Medio Ed Estremo Oriente, 1984), 187.

9. Rahul Sankrityayan, “Sanskrit palm-leaf manuscripts in Tibet”, Journal of the Bihar and Orissa Research Society 23 (1937): p. 39 and fn 4, ms. no. 266. Cited in Luciano Petech, Mediaeval History of Nepal (Rome: Istituto Italiano Per Il Medio Ed Estremo Oriente, 1984), p. 59, also fn 6 on same page.

10. Luciano Petech, Mediaeval History of Nepal (Rome: Istituto Italiano Per Il Medio Ed Estremo Oriente, 1984), 60.

11. Like the early steles at Kel-tol and Swayambhu from Manadeva's rule (464 – 505 CE), Slusser (1982) Appendix IV-1; water tanks, For example, the slab above the tutedhara at Khapimche-tol, Patan from 530 CE, Slusser (1982) Appendix IV-1; pedestals of images, Like the pedestal of Tunaldevi at Bishalnagar, Kathmandu (475 CE) and the Lazimpat Shivalingas from Manadeva's rule, Slusser (1982) Appendix IV-1.

12. Mary Shepherd Slusser, "On the Antiquity of Nepalese Metalcraft", Archives of Asian Art, 29 (1975-1976): 80-95

13. Licchavi stone inscriptions capture references to such copperplate inscriptions, as in inscr. 126 from Dhanavajra Vajracharya, Licchavikalka Abhilekh (Kathmandu: Institute of Nepal and Asian Studies, 1973, 474-478. The earliest known copperplate inscription is from 1100 CE, as described in Mahesh R. Pant and Aishvarya D. Sharma, “The two earliest copperplate inscriptions from Nepal”, Nepal Research Centre Miscellaneous Papers 12 (1977): 1-26.

14. Dilli Raman Regmi, Medieval Nepal (New Delhi: Rupa & Co., 2007), Vol 1, Appendix 18.

15. From Nepali translation provided by Gautamavajra Vajracharya, "Yangala, Yambu", Contributions to Nepalese Studies I:2 (1974): 93.

16. Mary S. Slusser and Gautamavajra Vajracharya, “Two Medieval Nepalese Buildings: An Architectural and Cultural Study”, Artibus Asiae 36-3 (1974): 174.

17. Mary S. Slusser and Gautamavajra Vajracharya, “Two Medieval Nepalese Buildings: An Architectural and Cultural Study”, Artibus Asiae 36-3 (1974): 209.

18. See early inscriptions in Regmi (2007) Appendix A, p 2 ff., including the one on the pedestal of the Uma Maheswar image at Ganchanani, Patan from 1012 CE. For later period and the transition to Nepal Bhasha, see inscriptions in Regmi (2007) Appendix A, p88 ff., such as the inscription from 1493 CE attached to the façade of the Yaksheswar temple in Bhaktapur.

19. Mary S. Slusser and Gautamavajra Vajracharya, “Two Medieval Nepalese Buildings: An Architectural and Cultural Study”, Artibus Asiae 36-3 (1974): 207, 209.

20. Yogi Naraharinath, "Kasthamandap", Sanskrit Sandesh 1:6 (1953) 4-10 as cited in Kashinath Tamot, " "Devo Gorakso" is not there", personal communication on unpublished manuscript.

21. Mary S. Slusser and Gautamavajra Vajracharya, “Two Medieval Nepalese Buildings: An Architectural and Cultural Study”, Artibus Asiae 36-3 (1974): 211.

22. Kashinath Tamot, “ “Devo Gorakso” is not there”, personal communication on unpublished manuscript.

23. Kamal Prakash Malla, “The Early Mediaeval Inscriptions of Nepala-maṇḍala”. Contributions to Nepalese Studies Vol 39, No. 1 , January 2012. Also published under the same title in Malla, Kamal Prakash, From Literature to Culture: Selected Writings on Nepalese Studies, 1980-2010, 465-493, Kathmandu: Himal Books, 2015, see p. 483 for passage on this inscription.

24. Dilli Raman Regmi, Medieval Nepal (New Delhi: Rupa & Co., 2007), Vol 1, Appendix 79.

25. Mary S. Slusser and Gautamavajra Vajracharya, “Two Medieval Nepalese Buildings: An Architectural and Cultural Study”, Artibus Asiae 36-3 (1974): 210.

26. R. Thapa, Kasthamandap, Ancient Nepal No. 3, Kathmandu (1968) 43.

27. personal communication, Sameer Tuladhar, assistant editor Asianart.com, Aug. 12, 2015.

28. Dilli Raman Regmi, Medieval Nepal (New Delhi: Rupa & Co., 2007), Vol 1, Appendix 54; Luciano Petech, Mediaeval History of Nepal (Rome: Istituto Italiano Per Il Medio Ed Estremo Oriente, 1984), 165.

29. Dilli Raman Regmi, Medieval Nepal (New Delhi: Rupa & Co., 2007), Vol 1, Appendix 85.

30. From Nepali translation in Itihas Samshodhanako Pramana Prameya (Lalitpur: Jagadamba Prakasan, 1962) Part I, 114.

31. Dilli Raman Regmi, Medieval Nepal (New Delhi: Rupa & Co., 2007), Vol 1, Appendix 99.

32. Luciano Petech, Mediaeval History of Nepal (Rome: Istituto Italiano Per Il Medio Ed Estremo Oriente, 1984), 202.

33. Gautamavajra Vajracharya, “Yangala, Yambu”, Contributions to Nepalese Studies I:2 (1974): 92.

34. Mary Shepherd Slusser, personal communication, Jul. 21, 2015.

35. Neils Gutschow, Architecture of the Newars: A History of Building Typologies and Details in Nepal (Chicago: Serindia, 2013), Vol II, 359.

1.Neils Gutschow, Architecture of the Newars: A History of Building Typologies and Details in Nepal (Chicago: Serindia, 2013), Vol II, 331, 359-60, 373.

2. Wolfgang Korn, The Traditional Architecture of the Kathmandu Valley (Kathmandu: Ratna Pustak Bhandar, 1998), 92.

3. Daniel Wright, History of Nepal (Cambridge: University Press, 1877), 211. See http://www.rebuildkasthamandap.com/legend for a stylized retelling.

4. Mary Shepherd Slusser, Nepal Mandala: A Cultural Study of the Kathmandu Valley, (Princeton: Princeton, 1982), Vol I, 89.

5. Neils Gutschow, Architecture of the Newars: A History of Building Typologies and Details in Nepal (Chicago: Serindia, 2013), Vol II, 345.

6. Dhanavajra Vajracharya, ed., Itihas Samshodhanako Pramana Prameya (Lalitpur: Jagadamba Prakasan, 1962) Part I, 110.

7. Neils Gutschow, Architecture of the Newars: A History of Building Typologies and Details in Nepal (Chicago: Serindia, 2013), Vol 1, 125.

8. Mary S. Slusser and Gautamavajra Vajracharya, “Two Medieval Nepalese Buildings: An Architectural and Cultural Study”, Artibus Asiae 36-3 (1974): 207, fn 34. See also Luciano Petech, Mediaeval History of Nepal (Rome: Istituto Italiano Per Il Medio Ed Estremo Oriente, 1984), 187.

9. Rahul Sankrityayan, “Sanskrit palm-leaf manuscripts in Tibet”, Journal of the Bihar and Orissa Research Society 23 (1937): p. 39 and fn 4, ms. no. 266. Cited in Luciano Petech, Mediaeval History of Nepal (Rome: Istituto Italiano Per Il Medio Ed Estremo Oriente, 1984), p. 59, also fn 6 on same page.

10. Luciano Petech, Mediaeval History of Nepal (Rome: Istituto Italiano Per Il Medio Ed Estremo Oriente, 1984), 60.

11. Like the early steles at Kel-tol and Swayambhu from Manadeva's rule (464 – 505 CE), Slusser (1982) Appendix IV-1; water tanks, For example, the slab above the tutedhara at Khapimche-tol, Patan from 530 CE, Slusser (1982) Appendix IV-1; pedestals of images, Like the pedestal of Tunaldevi at Bishalnagar, Kathmandu (475 CE) and the Lazimpat Shivalingas from Manadeva's rule, Slusser (1982) Appendix IV-1.

12. Mary Shepherd Slusser, "On the Antiquity of Nepalese Metalcraft", Archives of Asian Art, 29 (1975-1976): 80-95

13. Licchavi stone inscriptions capture references to such copperplate inscriptions, as in inscr. 126 from Dhanavajra Vajracharya, Licchavikalka Abhilekh (Kathmandu: Institute of Nepal and Asian Studies, 1973, 474-478. The earliest known copperplate inscription is from 1100 CE, as described in Mahesh R. Pant and Aishvarya D. Sharma, “The two earliest copperplate inscriptions from Nepal”, Nepal Research Centre Miscellaneous Papers 12 (1977): 1-26.

14. Dilli Raman Regmi, Medieval Nepal (New Delhi: Rupa & Co., 2007), Vol 1, Appendix 18.

15. From Nepali translation provided by Gautamavajra Vajracharya, "Yangala, Yambu", Contributions to Nepalese Studies I:2 (1974): 93.

16. Mary S. Slusser and Gautamavajra Vajracharya, “Two Medieval Nepalese Buildings: An Architectural and Cultural Study”, Artibus Asiae 36-3 (1974): 174.

17. Mary S. Slusser and Gautamavajra Vajracharya, “Two Medieval Nepalese Buildings: An Architectural and Cultural Study”, Artibus Asiae 36-3 (1974): 209.

18. See early inscriptions in Regmi (2007) Appendix A, p 2 ff., including the one on the pedestal of the Uma Maheswar image at Ganchanani, Patan from 1012 CE. For later period and the transition to Nepal Bhasha, see inscriptions in Regmi (2007) Appendix A, p88 ff., such as the inscription from 1493 CE attached to the façade of the Yaksheswar temple in Bhaktapur.

19. Mary S. Slusser and Gautamavajra Vajracharya, “Two Medieval Nepalese Buildings: An Architectural and Cultural Study”, Artibus Asiae 36-3 (1974): 207, 209.

20. Yogi Naraharinath, "Kasthamandap", Sanskrit Sandesh 1:6 (1953) 4-10 as cited in Kashinath Tamot, " "Devo Gorakso" is not there", personal communication on unpublished manuscript.

21. Mary S. Slusser and Gautamavajra Vajracharya, “Two Medieval Nepalese Buildings: An Architectural and Cultural Study”, Artibus Asiae 36-3 (1974): 211.

22. Kashinath Tamot, “ “Devo Gorakso” is not there”, personal communication on unpublished manuscript.

23. Kamal Prakash Malla, “The Early Mediaeval Inscriptions of Nepala-maṇḍala”. Contributions to Nepalese Studies Vol 39, No. 1 , January 2012. Also published under the same title in Malla, Kamal Prakash, From Literature to Culture: Selected Writings on Nepalese Studies, 1980-2010, 465-493, Kathmandu: Himal Books, 2015, see p. 483 for passage on this inscription.

24. Dilli Raman Regmi, Medieval Nepal (New Delhi: Rupa & Co., 2007), Vol 1, Appendix 79.

25. Mary S. Slusser and Gautamavajra Vajracharya, “Two Medieval Nepalese Buildings: An Architectural and Cultural Study”, Artibus Asiae 36-3 (1974): 210.

26. R. Thapa, Kasthamandap, Ancient Nepal No. 3, Kathmandu (1968) 43.

27. personal communication, Sameer Tuladhar, assistant editor Asianart.com, Aug. 12, 2015.

28. Dilli Raman Regmi, Medieval Nepal (New Delhi: Rupa & Co., 2007), Vol 1, Appendix 54; Luciano Petech, Mediaeval History of Nepal (Rome: Istituto Italiano Per Il Medio Ed Estremo Oriente, 1984), 165.

29. Dilli Raman Regmi, Medieval Nepal (New Delhi: Rupa & Co., 2007), Vol 1, Appendix 85.

30. From Nepali translation in Itihas Samshodhanako Pramana Prameya (Lalitpur: Jagadamba Prakasan, 1962) Part I, 114.

31. Dilli Raman Regmi, Medieval Nepal (New Delhi: Rupa & Co., 2007), Vol 1, Appendix 99.

32. Luciano Petech, Mediaeval History of Nepal (Rome: Istituto Italiano Per Il Medio Ed Estremo Oriente, 1984), 202.

33. Gautamavajra Vajracharya, “Yangala, Yambu”, Contributions to Nepalese Studies I:2 (1974): 92.

34. Mary Shepherd Slusser, personal communication, Jul. 21, 2015.

35. Neils Gutschow, Architecture of the Newars: A History of Building Typologies and Details in Nepal (Chicago: Serindia, 2013), Vol II, 359.

Bibliography

Bangdel, Dina. Reconsecration of Svayambhu Mahachaitya. In The Circle of Bliss: Buddhist Meditational Art, edited by John. C. Huntington, Dina Bangdel and Robert. A. F. Thurman, 112-115. Chicago: Serindia, 2003.

Doig, Desmond and Dubay Bhagat. Down History's Narrow Lanes. New Delhi: Braaten, 2009.

Gutschow, Neils. Architecture of the Newars: A History of Building Typologies and Details in Nepal. Chicago: Serindia, 2013. Three Volumes.

Hasrat, Bikrama Jit. History of Nepal, As Told by Its Own and Contemporary Chroniclers. Panjab: V. V. Research Institute, 1971.

Korn, Wolfgang. The Traditional Architecture of the Kathmandu Valley. Kathmandu: Ratna Pustak Bhandar, 1998.

Malla, Kamal Prakash. “The Early Mediaeval Inscriptions of Nepala-maṇḍala”. Contributions to Nepalese Studies Vol 39, No. 1 , January 2012. Also published under the same title in Malla, Kamal Prakash, From Literature to Culture: Selected Writings on Nepalese Studies, 1980-2010, 465-493, Kathmandu: Himal Books, 2015

Pant, Mahesh R. and Aishvarya D. Sharma. “The two earliest copperplate inscriptions from Nepal”. Nepal Research Centre Miscellaneous Papers 12 (1977): 1-26

Petech, Luciano. Mediaeval History of Nepal. Rome: Istituto Italiano Per Il Medio Ed Estremo Oriente, 1984.

Regmi, Dilli Raman. Medieval Nepal. New Delhi: Rupa & Co., 2007. Two Volumes.

Rospatt, Alexander V. The Past Renovations of the Svayambhucaitya. In Light of the Valley: Renewing the Sacret Art and Traditions of Svayambhu, edited by Tsering P. Gellek and Padma D. Maitland, 157-206. Cazadero: Dharma Publishing, 2011.

Sakya, Hemaraj, and Tulasi Ram Vaidya. Medieval Nepal: Colophons and Inscriptions. Kathmandu: Tulasi Ram Vaidya, 1970.

Sankrityayan, Rahul. “Second Search of Sanskrit palm-leaf manuscripts in Tibet”. Journal of the Bihar and Orissa Research Society 23 (1937): 1-57.

Sestini, Valerio and Enzo Somigli. Architettura Himalayana: Architettura tradizionale nella valle di Kathmandu / Himalayan Architecture: Traditional architecture in the Kathmandu Valley. Rome: Polistampa, 2007.

Slusser, Mary Shepherd. “On the Antiquity of Nepalese Metalcraft”. Archives of Asian Art 29: 80-95 (1975-1976).

Slusser, Mary Shepherd. Nepal Mandala: A Cultural Study of the Kathmandu Valley. Princeton: Princeton, 1982. Two Volumes.

Slusser, Mary Shepherd. “On a Sixteenth-Century Pictorial Pilgrim’s Guide from Nepal”. Archives of Asian Art 38 (1985): 6-36.

Slusser. Mary S. and Gautamavajra Vajracharya. “Two Medieval Nepalese Buildings: An Architectural and Cultural Study”. Artibus Asiae 36-3 (1974): 169-218.

Tamot, Kashinath. “ “Devo Gorakso” is not there”. Unpublished manuscript.

Thapa, Ramesh Jung. “Kasthamandapa”. Ancient Nepal 3 (1968): 41-43.

Tiwari, Sudarshan Raj. Temples of the Nepal Valley. Kathmandu: Himal Books, 2009.

Vajracharya, Dhanavajra, ed. Itihas Samshodhanako Pramana Prameya. Lalitpur: Jagadamba Prakasan, 1962.

Vajracharya, Dhanavajra. “Licchavikalka Shaasan Sambandhi Paaribhasik Shabdako Byakhya”. Purnima 3:2 (1965): 9-17.

Vajracharya, Dhanavajra. Licchavikalka Abhilekh. Kathmandu: Institute of Nepal and Asian Studies, 1973.

Vajracharya, Gautamavajra. “Yangala, Yambu”. Contributions to Nepalese Studies I:2 (1974): 90-98.

Wright, Daniel. History of Nepal. Cambridge: University Press, 1877.

Yogi Naraharinath. “Kasthamandap”. Sanskrit Sandesh 1:6 (1953): 4-10.

Bangdel, Dina. Reconsecration of Svayambhu Mahachaitya. In The Circle of Bliss: Buddhist Meditational Art, edited by John. C. Huntington, Dina Bangdel and Robert. A. F. Thurman, 112-115. Chicago: Serindia, 2003.

Doig, Desmond and Dubay Bhagat. Down History's Narrow Lanes. New Delhi: Braaten, 2009.

Gutschow, Neils. Architecture of the Newars: A History of Building Typologies and Details in Nepal. Chicago: Serindia, 2013. Three Volumes.

Hasrat, Bikrama Jit. History of Nepal, As Told by Its Own and Contemporary Chroniclers. Panjab: V. V. Research Institute, 1971.

Korn, Wolfgang. The Traditional Architecture of the Kathmandu Valley. Kathmandu: Ratna Pustak Bhandar, 1998.

Malla, Kamal Prakash. “The Early Mediaeval Inscriptions of Nepala-maṇḍala”. Contributions to Nepalese Studies Vol 39, No. 1 , January 2012. Also published under the same title in Malla, Kamal Prakash, From Literature to Culture: Selected Writings on Nepalese Studies, 1980-2010, 465-493, Kathmandu: Himal Books, 2015

Pant, Mahesh R. and Aishvarya D. Sharma. “The two earliest copperplate inscriptions from Nepal”. Nepal Research Centre Miscellaneous Papers 12 (1977): 1-26

Petech, Luciano. Mediaeval History of Nepal. Rome: Istituto Italiano Per Il Medio Ed Estremo Oriente, 1984.

Regmi, Dilli Raman. Medieval Nepal. New Delhi: Rupa & Co., 2007. Two Volumes.

Rospatt, Alexander V. The Past Renovations of the Svayambhucaitya. In Light of the Valley: Renewing the Sacret Art and Traditions of Svayambhu, edited by Tsering P. Gellek and Padma D. Maitland, 157-206. Cazadero: Dharma Publishing, 2011.

Sakya, Hemaraj, and Tulasi Ram Vaidya. Medieval Nepal: Colophons and Inscriptions. Kathmandu: Tulasi Ram Vaidya, 1970.

Sankrityayan, Rahul. “Second Search of Sanskrit palm-leaf manuscripts in Tibet”. Journal of the Bihar and Orissa Research Society 23 (1937): 1-57.

Sestini, Valerio and Enzo Somigli. Architettura Himalayana: Architettura tradizionale nella valle di Kathmandu / Himalayan Architecture: Traditional architecture in the Kathmandu Valley. Rome: Polistampa, 2007.

Slusser, Mary Shepherd. “On the Antiquity of Nepalese Metalcraft”. Archives of Asian Art 29: 80-95 (1975-1976).

Slusser, Mary Shepherd. Nepal Mandala: A Cultural Study of the Kathmandu Valley. Princeton: Princeton, 1982. Two Volumes.

Slusser, Mary Shepherd. “On a Sixteenth-Century Pictorial Pilgrim’s Guide from Nepal”. Archives of Asian Art 38 (1985): 6-36.

Slusser. Mary S. and Gautamavajra Vajracharya. “Two Medieval Nepalese Buildings: An Architectural and Cultural Study”. Artibus Asiae 36-3 (1974): 169-218.

Tamot, Kashinath. “ “Devo Gorakso” is not there”. Unpublished manuscript.

Thapa, Ramesh Jung. “Kasthamandapa”. Ancient Nepal 3 (1968): 41-43.

Tiwari, Sudarshan Raj. Temples of the Nepal Valley. Kathmandu: Himal Books, 2009.

Vajracharya, Dhanavajra, ed. Itihas Samshodhanako Pramana Prameya. Lalitpur: Jagadamba Prakasan, 1962.

Vajracharya, Dhanavajra. “Licchavikalka Shaasan Sambandhi Paaribhasik Shabdako Byakhya”. Purnima 3:2 (1965): 9-17.

Vajracharya, Dhanavajra. Licchavikalka Abhilekh. Kathmandu: Institute of Nepal and Asian Studies, 1973.

Vajracharya, Gautamavajra. “Yangala, Yambu”. Contributions to Nepalese Studies I:2 (1974): 90-98.

Wright, Daniel. History of Nepal. Cambridge: University Press, 1877.

Yogi Naraharinath. “Kasthamandap”. Sanskrit Sandesh 1:6 (1953): 4-10.

asianart.com | articles