A note on a disputed Khmer sculpture of three figures from the Bàkoṅ known as the Lord Umāgaṅgāpatīśvara

November 21, 2005

(click on the small image for full screen image with captions)

Introduction

At the time of its apogee (ca. 9.-13. c.) ancient Khmer culture created sculptures at a temple complex known as the Bàkoṅ [1The Bàkoṅ is located at Roluôḥ south of Prà Kô; cf. COE 2003: 104-105.], about 15 km SE. from present-day Siem Rǎp, Cambodia, that proved to be influential markers for a tradition culminating in the accomplishments of Aṅkor Vat. With the Khmer ruler Indravarman (reign 877/8-889/90) and his accession to the throne (ca. 877/8 A.D.) a new wave of building activity produced the temple of Prà Kô(sanctified 880 A.D.) as well as the Bàkoṅ. Only a few years later the ancestor temple of Lolei was erected by his son and successor, Yaśovarman I (reign 889 to ca. 900/10). Together these three form the ancient center of the town now known as Roluôḥ. Whereas Prà Kô also functioned as a temple for Jayavarman II and his consort Dharaṇīndradevī, for Rudravarman and Narendradevī as well as for Pṛthivīndravarman and Pṛthivīndradevī and whereas Lolei was erected in memory of Indravarman himself, the Bàkoṅ (foundation date: Śaka 803 = 5th March 881–23rd March 882) was used during the reign of Indravarman (ca. 877–89 A.D.) exclusively as a place of worship with Śiva as its central deity.

Time's grains of sand have worn away some of its former beauty. But the enduring solid material of the temple has preserved the monument with its inscriptions so well that its original set up and purpose are now, after efforts of restoration, evident upon sight. [2Cf. HIGHAM 1989: 327.]

The restoration has shown that the temple mound was once richly adorned with artistic friezes, sculptures, and carvings the motifs of which were taken from the mythological beliefs of the Khmer people as well as inspired by Indian sacred writings. Nevertheless a certain heterogeneity is noticeable due to varying components dating back to different periods of time. A group of three sacred figures hitherto known from various photographs taken in situ before their removal from the Bàkoṅ [3JESSUP 1997: 190 gives their present whereabouts as "Depot for the Conservation of Angkor".] and identified variously as the king with his two consorts, as Viṣṇu with two female attendants, and as the Lord Umāgaṅgāpatīśvara, i.e. the Hindu deity Śiva with his two divine consorts Umā and Gaṅgā, forms the subject-matter of investigation of this paper. It is my intention to present as convincing facts the overall local coherences that argue for the solution of the issue in question.

Historical Background

Indian brahmanical religion with its worship of the liṅga found its continuation in the Khmer world with rulers as keepers of the faith, as its propagators, as mediators between the divine and earthly realm and perhaps at some stage also with the liṅga as apotheosis of the ruler. Numerous Khmer inscriptions speak of this close interrelation of the faith and the ruler of the country. The royal lineage of Indravarman, a disciple of his spiritual master, the Brahman Śivasoma, is identified in the Bàkoṅ inscription IV [4G. Coedès was among the first to write about and transliterate the Bàkoṅ inscriptions; cf. COEDES 1937: 17-18 and 31-36. It was, however, necessary to improve the work of Coedès. The selected inscriptions are rendered adjusted to the standard of classical Sanskrit.] as follows:

rājñī rājaparaṃparoditavatī śrīrudravarmātmajā

rājaśrīnṛpatīndravarmatanayājātā satī yābhavat

patnī śrīpṛthivīndravarmanṛpateḥ kṣatrānvayāptodgates

tasyā bhūmipatiḥ suto nṛpanato yaḥ śrīndravarmāhvayaḥ [5Cf. COEDES 1937: 32 (Bàkoṅ IV = Prà Kô IV.5-6)]

A virtuous queen, who was born in a family with a succession of kings,

the daughter of Śrī Rudravarman and daughter's daughter of king Śrī Nṛpatīndravarman,

became the wife of king Śrī Pṛthivīndravarman, born of a Kṣatriya family.

She had a son called Śrī Indravarman, a king respected by other kings.[6His ascension to the throne is recorded in Bàkoṅ inscription III as the Śaka year 799, i.e. 877/78 A.D., as well as in the Prà Kô inscription III; cf. COEDES 1937: 32 and 24.]

Indravarman, known from historical accounts as a devout follower of Śaivism, erected his royal liṅga called Indreśvara [7On the controversy surrounding the liṅga bearing the name of the individual ruler and the suffix –īśvara, denoting an association of the monarch with Śiva cf. JESSUP 1997: 105-106. The erection of Śiva's liṅga by Indravarman at the Bàkoṅ is further mentioned in inscription XXXV.] in the center of his state temple, the Bàkoṅ. This temple was built shortly after his accession to the throne (881 A.D.), demonstrating thereby his secular and sacred command as given in Bàkoṅ XXIII.27: [8Cf. GOLZIO 2003: 51.]

tenāgnigagaṇavasubhir vasūpamenedam atra vasudātrā

śrīndreśvara iti liṅgaṃ tribhuvanacūḍāmaṇau nihitam [9Cf. COEDES 1937: 32.]

[In the year denoted by] Fire [3], Sky [0], and the Vasus [8] this [king],

comparable to the Vasus as a giver of wealth (vasu), established the liṅga

"Śrī Indreśvara" here on the Tribhuvanacūḍāmaṇi [10Cf. COEDES 1937: 34, n. 4 for this technical term.].

The temple complex

General outline of the Bàkoṅ

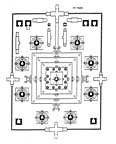

Map of AngkorThe Bàkoṅ, an artificial temple mound, was the centre of the ancient town of Hariharālaya. [11The complex was restored to its present shape in 1936/7-1943 A.D. under Maurice Glaize.], [12Cf. COE 2003: 104-105.] It was built in an architectural outline based on Brahmanic cosmological concepts [13For the cosmological concept of Mount Meru as found in Indian texts cf. KIRFEL 1967: 15ff and JESSUP 1997: 101-102. Cf. STIERLIN 1994: 81-82 for the religious implications of Khmer temple architecture.]. A rectangle with its longer sides facing North and South forms the basic outer enclosure of this complex. Two main passages on the East and West lead through the outer concentric enclosure to the interior. The inner concentric enclosure is surrounded by a moat. Four entrances give access to the inner enclosure with two major entrances at the East and West and two minor, one in the North as well as in the South, and allow passage to the innermost part of the sacred maṇḍala. [14Cf. STIERLIN 1994: 25.] From the East an erstwhile aisle flanked by two elongated buildings guides the visitor to the central mound rising 15m in height.

Outline of the Bàkoṅ ensemble [15Cf. BUNCE 2002: 177 for the outline of the Bàkoṅ.]Four axial stairways lead up five gradually receding square tiers to its crown, a sacred tower rebuilt at a later date perhaps in the 12th cent. A.D. and erected on an lotus-shaped base. Twelve smaller towers surround the peak on the fourth tier. Elephants [16Elephants were according to JESSUP 1997. 286: "Appearing first toward the end of the ninth century on the tiers of the pyramid at Bakong... ".] successively smaller in size stand at the corner of the first three tiers of the base. Eight minor stone islands of varying size, with partially intact sanctuary towers [17Cf. PARMENTIER 1919, Pl. XVI for a pen drawing of one of these sanctuary towers.] , surround the mountain's base (67 x 95m) [18Cf. GROSLIER 1965: 110.], two at each side. Mount Meru, seat of the gods, and its eight satellites, facing East, the direction of the sunrise and of Hindu worship are here embodied in brick as a representation of the cosmic order, and still impress, though with a derelict appearance, their former importance upon the viewer. [19For an in-depth description of the temple's layout cf. BRIGGS 1951: 101 and JACQUES 1997: 68. Cf. further MAZZEO 1979: 53ff and ROONEY 1994: 182-183.]

|

|

|

The lower eight square sanctuaries of stuccoed brick, two at each of the four sides of the temple mountain's base, are considered as contemporaneous with the founding of the temple. They functioned as receptacles for the worship of Śiva's eight divine forms (mūrti). [21Cf. BUNCE 2002: 177.]

The shrine tower (prasat) in the North-East

Bàkoṅ shrine tower

in the North-East [22For the picture cf. STIERLIN 1994: 27.]

The two sanctuaries East of the temple mound survive only as stone bases. A group of three sculptured figures, the subject of investigation of this paper, was found in the North-East shrine.

This shrine tower (prasat) with a square as its base and two upper indented tiers of an octogonal form carried once on its upper level a sanctuary tower. The tower's shape can be guessed at from those that survive intact in the South and West of the central monument. [23Cf. PARMENTIER 1919: Pl. XVI.] It contained a square cella and had four entrances. Three of these were false doors whereas the real one was the one to the East. [24Cf. MAZZEO 1979: 50.] Four axial stairways each flanked by a crouching lion still lead to the central sanctuary. The remaining door frame of the main entrance to the East, slightly worn-down, has an embellished octogonal column at each side of the doorjambs that have fine line carvings. [25For the colums and the lintel cf. MAZZEO 1979: 50.]

It carries a magnificent Khmer lintel with a play of sumptuous arabesques over a plain background; its rhythmic, luxuriant foliage with figurative motifs and the mounted head of a grinning kāla with bulbous eyes, pointed ears, and a frightening row of upper teeth adorn the sacred passage. [26For examples of Khmer lintels from primitive to 9th cent. types cf. GLAIZE 1993: Pl IV- Evolution du linteau jusqu'au Xe siècle. Cf. JACQUES 1990: 177-178 for lintels of the Prà Kô-style.]

column |

column |

tower in the North-East |

The interior of the cella was, according to the Bàkoṅ inscriptions XXIV-V and XXVIII, to house a divine form (mūrti) [27On the aṣṭamūrti of Śiva and their respective names cf. MEINHARD 1928: 9-14 and BHATTACHARYA 1961: 58-60. For further reference cf. COEDES 1937: 34, n. 7.] of Śiva:

śrīndreśvarāṅgane 'py atra dṛśām

utsavakāriṇī tvaṣṭur apy avisaṃvādimanovismayadāyini (XXIV)

ilāni(lāgnicandrārka-)sa(l)ilākāśayajvan(aḥ)

rājav(ṛtt)īri(t)e(śa)sya [28The reconstruction of the incomplete inscription is commented on in COEDES 1937: 34, n. 6.] so 'ṣṭamūrtīr atiṣṭhipat (XXV)

teṣāṃ vicitraśikharān prāsādān sa

śilāmayān cakāra lalitākārān dharmabījāṅkurān iva (XXVIII) [29Cf. COEDES 1937: 32-33. Inscriptions XXVI-XXVII are badly damaged.]

And here, in Śrī Indravarman's court, which causes delight to the eyes and

unfailing admiration even to Tvaṣṭṛ (XXIV)

he established the eight forms [30Cf. MEINHARD 1928: 9ff.] (mūrti) of the Lord, named according to royal custom,

Earth (ilā), Wind (anila), Fire (agni), Moon (candra), Sun (arka),

Water (salila), Ether (ākāśa), and Sacrificer (yajvan). (XXV)

For them he built towers (prāsāda) of stone with wonderful tops [and]

of beautiful shapes as the sprouts of the seeds of the law. (XXVIII)

A group of three figures found at the Bàkoṅ

State of preservation

Sculptures found at

the site [32Cf. MAZZEO 1979: 51.]

View from rear [34Cf. JACQUES 1990: 47.]

The presence of a colossal group of three sculpted sandstone figures, anonymously carved, unsigned and undated, with a dominant male central figure and two smaller, female accompanying statues found elevated on a three stepped base in the middle of the above mentioned cella [31Cf. BHATTACHARYA 1961: 85, Pl. III-IV with a depiction of the same sculptural triad but in a more worn out condition. Cf. further MAZZEO 1979: 51.] is supported by in situ inscriptions from the reign of Indravarman.

Bàkoṅ inscription XXIX speaks of the erection of a sculpture representing the Lord Umāgaṅgāpatīśvara which was previously installed there:

umāgaṅgābhujalatāsaṃśliṣṭājaghanasthalam

sa īśvaraṃ sthāpitavān umāgaṅgāpatīśvaram (XXIX) [33Cf. COEDES 1937: 33.][Śri Indravarman] established the Lord Umāgaṅgāpatīśvara

whose buttock is entwined by the liana-like arms of Umā and Gaṅgā.

The group found is a free-standing sculpture carved in the round without any support arch for arms and hands. The whole group seems to have been originally carved from a single block of sandstone. Formerly the three figures were linked with a hand of each goddess resting on the back of the god's respective thigh. Major parts of their arms are still attached to the back. Though rather modest in design the statues are awe-inspiring, the dominant male in his physical strength and vigour and the females, modeled with sensitivity following canonical forms of beauty, in their subdued sensuality. The striking feature of the whole composition is the way in which, on to the massive surface of the images, the folds of the waist-cloth at the front of the belly and thighs flow into a classical elegantly sinuous linear relief.

The male central figure

The central male figure with a height of 130 cm [35Cf. RAWSON 1990: 52.] faced East. Though the head and most of the arms are missing it is otherwise quite complete. Originally it had four arms. Its shoulders are broad and the remaining parts of the arms and the two legs especially thick with a fullness of the form approaching stoutness. The body in standing posture with feet slightly apart radiates might in peaceful repose. Neither ornaments nor footwear adorn the figure. The sparsely carved clothing shows only a traditional hip-cloth (saṃbat) fastened with a girdle around the waist. This mainly plain garment follows closely the shape of the upper thighs. A shallow fan of pleats projects on to the belly above the girdle, while below it extend sinuous pointed fans with rippled ends, half-way to the knees. The anchor-like shape of the falling front panel has a single layer with pleats remarkably precise. [36Compare JESSUP 1997: 198, Fig. 33 with a similar representation.]

The accompanying two female figures

Female drapery

On the same level as the male were discovered on each side a female figure facing East. They are smaller than the central figure, the shoulders barely reaching the waist of the male. [37The exact measurements are as yet unknown to me.] The head and the two arms of each figure are lost. Their feet are slightly apart. Voluptuous but peaceful the harmonious bodily proportions bear a simple grace. The better preserved of the female figures clearly shows the two long creases essential of canonical beauty running below the bare breasts. [38Compare JESSUP 1997: 201, Pl. 35.] Neither ornaments nor footwear bedeck the figures. Only a girdle holds the lower wrap-around skirt, partly pleated, with a folded-over upper extension covering the body. Its long, central fan of pleats reaches to the ankles. A special petal-like swag of pleats is folded down over from behind the girdle into a very feminine and suggestive loop, with a curvilinear pointed tail cast out on one hip. These ornamental motifs follow slowly double curves slightly square in form. The front with its folded-over upper extension fanning out in a semicircle and the hanging triangular corner of the inner edge – both lost on the figure to the left of the central one – was a new manner of draping the skirt cloth that would influence the Bakheng style, which followed immediately afterwards.

As with these figures, which according to B. Ph. Groslier follow the PràKô-style, [39For the principle decorative features of the Prà Kô-style cf. BRIGGS 1951: 100-101 and GROSLIER 1965: 106. During the pre-Angkor period there were few anthropomorphic representations of Śiva, who was usually depicted in the symbolic form of the liṅga.] and with others of this period, a growing schematization of the drapery becomes visible. A comparison of preceding and subsequent costumes show that the foundation for the classicism of Angkor drapery can be found with these sculptures of the Bàkoṅ. [40For the female divinity cf. JESSUP 1997: 201 and compare JESSUP 1997: 190, Fig. 2 or the hip-cloth on ibid. p. 218, Fig. 46 as examples of a perpetuation of this style.]

A disputed identity

Since the habitat of these statues was the sanctuary of a shrine tower, the question arises as to what they represent. Known inscriptions speak of the local ruler Indravarman as a worshipper of Śiva, his installing a liṅga at the cosmic Bàkoṅ maṇḍala, [41Cf. Bàkoṅ inscriptions XXIII and XXXV.] the eight shrine towers as santuaries for Śiva's eight respective forms (mūrti), and of statues such as the Lord Umāgaṅgāpatīśvara erected by him. The inference that the sculpture found therefore represents Śiva and his two consorts is nevertheless a debated issue. [42Besides the erection of a representation of the Lord Umāgaṅgāpatīśvara those of Viṣṇusvāmin, Īśāna, Śārṅgin, Indrāṇī as well as a Mahiṣāsuramardanī are also mentioned in the inscriptions XXX-XXXIV. No additional images are spoken of in the remaining intact Bàkoṅ inscriptions.]

C. Jacques proposed another identification for this group. The four arms of the central figure of the triad as well as marks on the base point, according to C. Jacques, to a representation of Viṣṇu:

"Vishnu mit seinen zwei Gemahlinnen. Dieses Ensemble war lange Zeit unter dem Namen Umagangapatisvara (!) 'Der Herr (Shiva), Gemahl von Uma (!) und Ganga (!)' bekannt, eine Gottheit, von deren Schöpfung auf der Säuleninschrift des Tempels die Rede ist. In Wirklichkeit handelt es sich aber um Vishnu (!), möglicherweise mit Cri (!) und Bu (!)... was deutlich an den vier Armen zu sehen ist...". [43Cf. JACQUES 1990: 47. This assertion was already challenged in JESSUP 1997: 191, n. 41.]

This assertion, however, is in no way supported by any remaining Bàkoṅ inscrip-tion [44Of the entire set of 49 stanzas plus one line of homage to Śri Indreśvara at the very beginning only two inscriptions, i.e. XXVI-XXVII, are nearly entirely damaged.]. His argument is, furthermore, unfounded since a four-armed Śiva existed as Hindu iconography shows. [45Cf. RAO 1968: PL. Xc.]

B. Ph. Groslier and Ph. Rawson on the other hand argued for a representation of the king and his two wives:

"The most interesting of Indravarman's sculptures is the colossal group of three figures on the Bakon (!) ... which probably represents the king with two of his wives, one on each side, in the guise of Shiva with Umā and Gaṅgā... ". [46Cf. GROSLIER 1965: 106 and RAWSON 1990: 52.]

Convincing evidence in support, however, has not been found. [47For a further clarification of this issue it might prove useful to investigate the rendering of verse VI of the Pràḥ Kô inscription K. 713 and its implications within the context of the Khmer devarāja cult.] An identification is made especially difficult since head and attributes are lost. The anthropomorphous style of representation as well as engraved drapery are common in the context of Khmer sculptured divinities.

Religious Concepts of 9th cent. Cambodia

The religious tradition and form of Śiva worship that prevailed at the Bàkoṅ and is mentioned in the inscriptions is an antrophomorphic form of worship with its roots in the Indian epic-purāṇic tradition. [48Śaivism includes a diversity of theistic tendencies; cf. MICHAELS 1998: 237-239. The Bàkoṅ inscriptions speak of the epic-purāṇic tradition of Śaivism supported by those brahmanic tendencies that are geared to the Veda. The worship of anthropomorphic representations of Śiva forms part of it.] Inscriptions I-II pay homage to Śiva, the supreme Self (paramātman) who is by nature without parts (niṣkala). He is adored as the one who assumes forms by His own will (svecchayā dhṛtamūrti) and manifests Himself, although One (eka), dwelling in many (anekeṣu) simultaneously. [49Cf. Bàkoṅ inscription I-II (= Prà Kô I-II) in COEDES 1937: 19. Cf. BHATTACHARYA 1961: 59ff on this religious concept.]

In this tradition Śiva is mythologically linked with Gaṅgā [50Cf. STIETENCRON 1972: 48-49.] as well as with Pārvatī/ Umā. [51Though not prominent in the Vedas, Gaṅgā assumes a position of great importance in the Purāṇas and is especially known from the Gaṅgāvataraṇa myth. Gaṅgā embodies on an esoteric level Śiva's active energy (śakti) through which the qualityless, unspeakable Sadāśiva manifests himself in the world, nourishing all the manifest universe. As this form Gaṅgā makes Śiva's activitiy in the world possible. Pārvatī/Umā is known from the Śiva-purāṇa and Kūrmapurāṇa as the form of the Self of all, as Prakṛti, Śivā, the highest bliss. She was the goddess Maheśvarī as mentioned in KRAMRISCH 1981: 342.] Though the representation of Śiva accompanied by Umā and Gaṅgā is an unknown iconographic feature in mainland India, it was, as K. Bhattacharya pointed out, known in Bengal. [52Cf. BHATTACHARYA 1961: 85 and ibid. n. 5.]

Conclusion

Mainly the coherent testimony of the Bàkoṅ inscriptions [53Cf. especially Bàkoṅ XXII-XXXI. A revision of the Roluôḥ corpus of inscriptions is undertaken by Prof. K. Bhattacharya, Paris, and Dr. K.-H. Golzio, Bonn, with the prospect of a future publication.] supported by the architectural set up of the temple complex strengthens the assumption that the Khmer sculpture in question represents the Hindu triad Śiva, Umā, and Gaṅgā as part of an antrophomorphic form of worship of the Indian epic-purāṇic tradition. [54To those already mentioned one has to add Bàkoṅ inscription XLIX (= Prà Kô XL), cf. COEDES 1937: 22, supporting Khmer worship with its roots in the Indian purāṇic tradition since it speaks of Śiva's abode (śivapada) as a place of rebirth for Śiva's devotees.] Especially the first half of inscription XXIX is decisive; it found its exact depiction in the group of three figures in question.

The iconography of this type of triad, Śiva with two divine consorts Umā and Gaṅgā, is bolstered by other findings. G. Coedès and K. Bhattacharya mention the inscription of Kapilapura with a reference to a representation of Śiva accompanied by Bhavānī (Umā) and Jāhnavī (Gaṅgā). [55Cf. COEDES 1937: 35, n. 1 and BHATTACHARYA 1961: 85, 93-94.] A further inscription of Rājendravarman (961 A.D.) at the East Mébǒn supports the reference of the Kapilapura inscription. [56Cf. BHATTACHARYA 1961: 93]

One may therefore on the basis of the given facts conclude that this in no way singular Cambodian feature depicts with the sculpture of three figures in question the divine trinity Śiva with Umā and Gaṅgā. [57Special thanks go to Prof. K. Bhattacharya, Paris, and Dr. K.-H. Golzio, Bonn, for sharing their ideas and resources on the Bàkoṅ inscriptions. Dr. W. Southworth, Leiden, and M.A. P. Wyzlic, Bonn, rendered valuable assistance. To all I extend my gratefulness for their kindness and support.]