|

Nor is it entirely accurate to claim that Europeans were the only consumers

of European paintings in the Indies, since there had been a small but significant

interest in European paintings amongst the Indonesian aristocracy for several

centuries. This interest continued right through to the modern period, as

demonstrated by the fact that several European artists of the Mooi Indie

style were invited to work in the palaces of Javanese princes; the Dutch

artist Gijsbert Nonus Op Ten Noort (1821-1870) worked in the palace of the

Susuhunan of Surakarta, and his fellow countryman, Isaac Isreals (1865-1934),

also worked in Surakarta in the court of the Mangkunegara. Even well into

the twentieth century, former Indonesian president Sukarno particularly

favoured the work of Mooi Indie artist Ernest Dezentjé (1885-1972,

figure 3) and gave his paintings as gifts to President Tito of Yugoslavia.

In fact, the introduction to the multi-volume publication illustrating paintings

from Dr. Sukarno's collection indicates that his aesthetic tastes favoured

romantic, naturalistic landscapes, given his preference for scenes of "green

mountains sprawling across the golden paddy fields, the little brooks meandering

over the stones, and the shimmering reflections of clouds fondling with

the sunshine on the hilltops."

There is a similar assumption that Mooi Indie art was produced exclusively

by Europeans, most of whom were merely idle tourists in the Indies for

brief periods of time, and could therefore not have had any real understanding

of or connection with the people and places they painted; their art must

then be, by definition, superficial and trivial. Certainly, specimens

of this type of tourist-artist did exist in significant numbers, and the

aforementioned Isaac Isreals is perhaps the best example. While on his

way to Java, this Dutch-born artist wrote "this is a useless journey,

I might as well admit it to myself, but there will be so much pleasure

in store for me at my return." When he returned to Europe three years

later, his opinion of the East had hardly changed; at that time he wrote

of his relief of finally returning to the true "centre of the world."

(4)

While in Indonesia, Isreals accurately recorded his surroundings in his

post-Impressionist style, but made no attempt to connect with or to study

at any depth the people or way of life of Indonesia. Aside from the subject

matter of a small number of canvases, his stay left no lasting impression

on his art, and even these few Indies-inspired works hardly differ from

the work he did previously and afterwards in Europe. As one art critic

at the time noted, "it is as if he is trying to make himself heard

by the Javanese people by yelling at them in Dutch…it is as if he

carried his Hague studio with him like a snail's shell."(5)

|

But if we look a little closer we can also find many examples of Mooi

Indie artists who do not fit this tourist-artist stereotype. There was,

for example, a handful of Mooi Indie artists who were Indonesian, most

notably Abdullah Suriosubroto (1878-1941, figure 5), Mas Pirngadie (1865-1936),

and Wakidi (1889-1980, figure 7), who were all popular within colonial

society. Persagi later branded these artists as those who, "divorced

from the local reality, gave their allegiance to the Dutch," and

most art historical texts follow suit by dismissing their work with statements

such that they "attached value more to decorative rather than artistic

merit." But we would do well to remember that these artists were

the teachers and mentors for members of the next generation of Indonesian

artists; Mas Pirngadie, for example, taught Sudjojono and Soermo, both

of whom were later members of Persagi.

Perhaps more significant than these few Indonesian Mooi Indie artists

was the large number of those who were both Indonesian and European. As

greater numbers of Europeans came to Indonesia, there developed an increasing

distinction between those who had been born in Europe and those Indo-European

families who had settled in the Indies, many of whom were of mixed blood,

who comprised fully seventy-five percent of the "European" community

in Indonesia. With this in mind, a consideration of the Mooi Indie artists

becomes considerably more complex, because certainly the "shallow,

tourist-like" response to Indonesia experienced by temporary visitors

can not be equated with the relationship to the Indonesian landscape,

politics, and people experienced by such artists as Willem Bleckmann (1853-1952),

Leo Eland (1884-1952, figure 6) and the aforementioned Ernest Dezentjé

(figure 3), all of whom were born and raised in the Indies and were Javanese

on their mothers' side. With a consideration of the differing social status

of Indonesians, Indo-Europeans, and Europeans in mind, we should expect

to see evidence of these differences made manifest in the art of the period,

and indeed this bears out particularly well when we investigate the number

and nature of the images of landscapes and mountains in the art produced

by different types of Mooi Indie artists.

It would be difficult to overstate the importance of the social, artistic,

and spiritual roles played by the symbol of the mountain in Indonesia

since prehistoric times. According to Joseph Fischer, "to understand

the meaning, symbolism and historic importance of the mountain is to begin

to comprehend Indonesian belief and culture, particularly that of Java

and Bali." (6)

Mountains were traditionally seen as spiritually-charged sites; they are

central to both Hindu and Buddhist world views as symbols of Mount Meru,

and were considered the vehicles through which the gods could descend

to this world and from which human beings could communicate with the heavenly

realms. In this capacity as mediator between this world and the next,

the mountain is particularly connected to the figure of the artist, whose

traditional role has been a similar means by which the gap between this

world and the spiritual realms could be bridged.

|

All of these connotations make the mountain a powerful symbol in the

Indonesian psyche, and imbues views of the Indonesian landscape with the

idea of kagunan, a local aesthetic rooted in the image of and

the language describing the mountain. It is, of course, impossible to

ignore the topographical omnipresence of mountains and volcanoes in the

region, particularly in Java and Bali, but for those for whom the spiritual

and symbolic importance of the mountain has been emphasised over many

years and though successive cultural and religious contexts, the image

of the mountain will be particularly sought out; for such people who express

themselves through the arts, it should be expected that the image of the

mountain will be a recurring theme. Indeed, this is supported by the fact

that the mountain and its variants, such as the tree of life, the gunungan

symbol of the wayang performances, the triangle and the stupa,

are some of the most common themes in traditional Indonesian art.

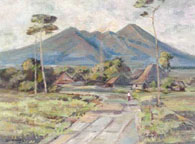

When we turn to the modern period, even a cursory examination reveals

that European Mooi Indie artists tended to favour town views, images of

anonymous Indonesians, or folkloristic scenes of the Indonesian way of

life. Landscapes painted by European artists often did not focus on the

prominence of mountains, but rather let them blend discretely into the

background, as in "Landscape" by Henry van Velthuysen (1881

- 1954, figure 1), for example. When they did focus their attention on

depicting mountains, they often did so in order to paint particular places

named and located in space and time: cartographer's mountains such as

that captured in "Pemandangan Di Modjo-Agung" by Gerard Adolfs

(1987 - 1908, figure 2).

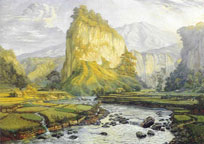

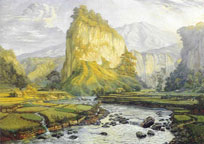

In contrast, images by Indo-European and Indonesian Mooi Indie artists are

much less likely to be topographical studies of specific landscapes than

they are an attempt to capture the idea of the mountain, expressive of

the kagunan sensibility that frames the mountain as the balancing

central force in the physical and spiritual landscape. Such artists used

their time "to go to quiet places… far from the crowds, in

order to meditate upon the natural environment they intended to paint.

Apparently, these painters found 'a friend' who greeted their finest feelings

with joy in the natural environment that stretched as far as the eye could

see in its original beauty and peacefulness." (7)

The canvases that resulted from such connection to the landscape, while

quite often representative of actual scenes, are nevertheless imbued with

a symbolic sense of the idea of landscape more generally, with the mountain

as central, both in composition and importance.

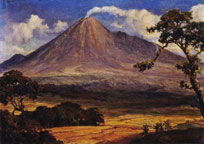

This is true both of the Indo-European such as Ernest Dezentjé

(figure 3), Leo Eland (figure 6) and others, as well as the Indonesian

artists who specialised in the Mooi Indie style (figures 5, 7 and 8).

And although there are few landscapes by Raden Saleh (1807 - 1880), who

was the first Indonesian artist to triumph in western painting and who

is revered as the grandfather of Indonesian painting, those that he did

create do often feature the same kind of dominant, forceful mountain (figure

9). Even Sudjojono himself, for all his published acrimony towards Mooi

Indie, at times himself also painted landscapes in which commanding peaks

rise up from the Indonesian land and villages as perfect metaphors for

Indonesian strength and independence (figure 4).

|

Thus, if not for the colonists who were often the consumers

of many of these paintings, then at least for the artists who painted

them, the mountain images in Mooi Indie paintings by Indonesian and Indo-European

artists were not simply decorative effect, but were also symbols of a

uniquely Indonesian spirituality and aesthetic belief. The western painting

techniques and styles that are used to classify artists as Mooi Indie,

and thus as foreigners, invaders, and oppressors, are in fact of minor

significance when weighed against the content, the themes and the motifs

that such artists use to communicate their spiritual, political and personal

relationship to Indonesia.

|